This is Part 4 in the THB series — Climate Fueled Extreme Weather. You can find Part 1 here Part 2 here and Part 3 here. Each can be read on their own, but I encourage you to start from the beginning as each installment draws on the ones before.

Everyone knows that in recent years climate change has fueled floods, storms, and drought, making them much more common and intense. For instance, a 2023 Pew Research poll found that 84% of Americans believed that climate change had contributed to worsening floods, storms, or drought in their local communities.

The widespread public belief in climate change as a cause of the weather events that we experience and see on social media is nowadays conventional wisdom. It is a fact so obvious that it barely needs to be supported at all.

As renowned climate scientist Michael Mann explains, the detection of climate change is as simple as “turn on the television, read the newspaper or look out the window to see what is increasingly obvious to many.”

Given these apparently undeniable realities we might wonder why the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) spends so much time and effort on assessing the science of the detection and attribution of changes in climate. Well, for the IPCC at least, science still matters.

Given widespread popular beliefs and media-friendly experts willing to cater to those beliefs, many are surprised, shocked even, to learn that the IPCC has arrived at conclusions on extreme events and climate change that are completely at odds with conventional wisdom and popular opinion.

According to the IPCC, we cannot in fact simply “look out the widow” and observe climate change — even for video-friendly hurricanes, floods, and drought. In fact, the IPCC currently concludes that we will not this century be able to detect with high confidence changes in the statistics of most weather events beyond internal variability — and this holds even if the world were to follow a projected implausible RCP8.5 future.

The massive gap between public and media opinion and the state of scientific understandings of trends in extreme events is as large as any I’ve encountered on any topic over the past 30 years.(1) The fact that this gap is encouraged and reinforced by many who profess climate expertise makes this issue truly unique among issues where science meets policy and politics.

Let’s take a look at the details.

In Part 3, I reviewed the concept of the “time of emergence” of the signal of a change in climate. The IPCC in its most recent assessment report (AR6) explains:

In the context of human influence on climate, the objective of emergence studies is the search for the appearance of a signal characterizing an anthropogenically-forced change relatively to the climate variability of a reference period, defined as the noise.

The IPCC further explains that the “time of emergence” is closely related to the concept of the “detection” of change in the statistics of a weather or climate variable, without necessarily identifying the reason(s) for that change:(2)

Related to the concept of emergence is the detection of change (Chapter 3). Detection of change is defined as the process of demonstrating that some aspect of the climate, or a system affected by climate, has changed in some defined statistical sense, often using spatially aggregating methods that try to maximize S/N, such as ‘fingerprints’ (e.g., Hegerl et al., 1996), without providing a reason for that change. An identified change is detected in observations if its likelihood of occurrence by chance due to internal variability alone is determined to be small, for example, <10% (Glossary).

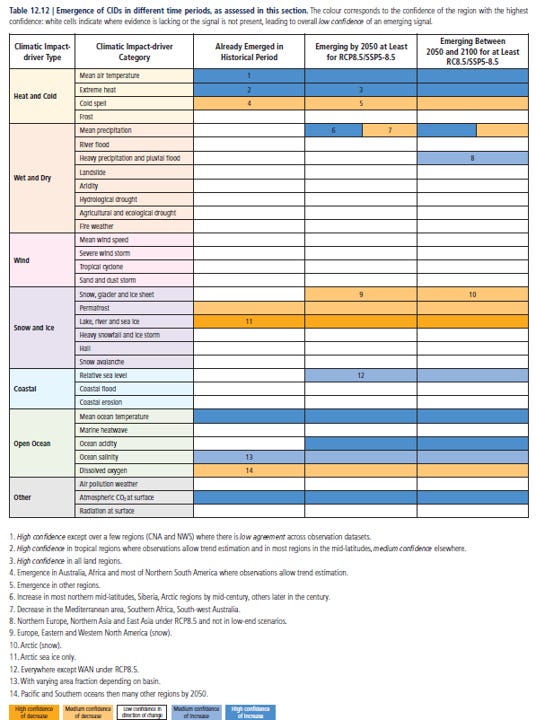

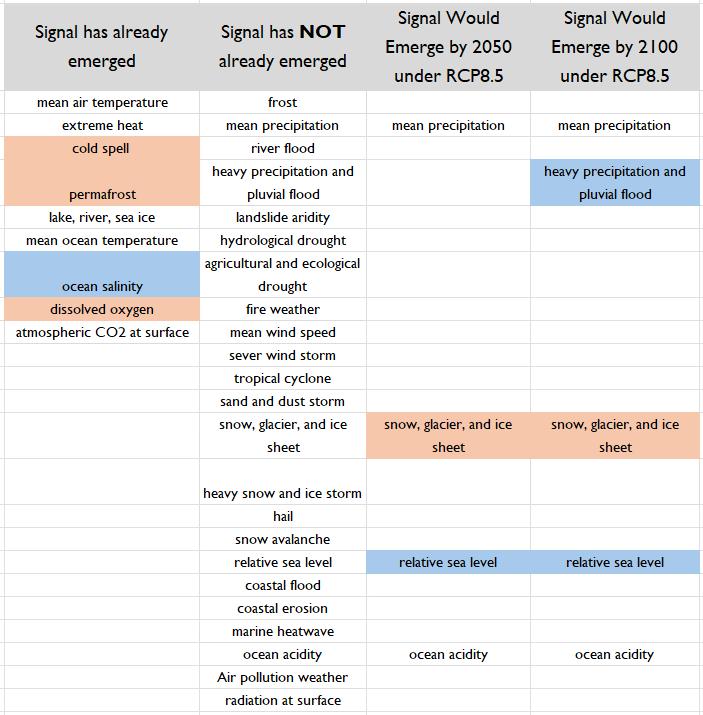

The IPCC AR6 very helpfully summarized its conclusions on the time of emergence for observed and projected changes in 32 weather and climate variables, with high (90%) and medium (50%) confidence levels. The table below summarizes the IPCC conclusions.3

These conclusions represent the most recent IPCC’s snapshot in time of scientific understandings and like all areas of science, assessment conclusions may change with new evidence and analyses. However, given the robustness of these findings in the context of the challenges to achieving high confidence in detection of change, these findings are unlikely to change anytime soon.

Some key takeaways:

- You cannot look out the window and detect climate change;

- Formal detection of change in the statistics of extreme weather beyond observed variability is highly unlikely for most metrics anytime soon, apart from those associated with temperature changes — according to the IPCC;

- Ubiquitous claims that hurricanes, floods, and drought (and various other extremes) have become more intense or frequent (regardless of cause) in the context of documented variability are simply wrong;

- Many credentialed experts and journalists are intentionally promoting misinformation related to extreme events;

- Many other experts and journalists know better and say nothing.

At the scale of weather events that affect people and ecosystems the challenges of detection are significantly greater. The IPCC AR6 explains that the detection and attribution of trends in the statistics of weather and climate variables is more difficult at regional and local scales:

Attribution at sub-continental and regional scales is usually more complicated than at the global scale due to various factors: a larger contribution from internal variability, an increased similarity among the responses to different external forcings leading to a more difficult discrimination of their effects, the importance at regional scale of some omitted forcings in global model simulations, and model biases related to the representation of small-scale phenomena.

The variables for which the IPCC has detected changes are primarily associated with temperature — many will be surprised that the IPCC does not claim high confidencein the detection of changes in precipitation for most regions:

The robustness of regional-scale attribution differs strongly between temperature and precipitation changes. While the influence of anthropogenic forcing on regional temperature long-term change has been detected and attributed in almost all land regions, a robust detection and attribution of human influence on regional precipitation change has not yet fully occurred for many land regions (Section 10.4.3). Although the contribution of anthropogenic forcing to long-term regional precipitation change has been detected in some regions, a robust quantification of the contributions of different drivers remains elusive. The delayed emergence of the anthropogenic precipitation fingerprint with respect to temperature is likely due to the opposing sign of the fast and slow land precipitation forced responses and time-dependent SST change patterns (Sections 8.2.1 and Section 10.4.3), stronger internal variability (Section 10.3.4.3) as well as larger observational uncertainty (Section 10.2) and impact of model biases.

Climate science finds itself in an odd situation. With respect to weather and climate extremes, public opinion and political rhetoric has gone far beyond what data and research can support. When scientists offer correctives to this divergence they can be seen as downplaying the seriousness of climate change as a political issue, even if those correctives are scientifically accurate and consistent with consensus views.

That divergence has also created a demand for the production of “research” to support the false claims — and some scientists and officials have responded to such demands with flawed science and manufactured data — and see professional rewards as a result.

At the same time, there are also enormous professional and social pressures on climate experts not to correct the rampant misinformation on extreme events. I get it— When I testified before the House and Senate a decade a ago on what the IPCC said about extreme events (much as I have in this series) I found myself targeted by the Obama White House which led to a Congressional investigation, and eventually, contributed to my leaving academia altogether.

So far, and much to their credit, the IPCC WG1 has stood strong against the pathological politicization of climate science. The same cannot be said for IPCC WG2 or the most recent U.S. National Climate Assessment. Can the IPCC WG1 continue to stand strong?

I’ll end today’s installment with a quote from Nate Silver, which aptly summarizes where the climate science community finds itself today:

I used to confidently assume I was on the side of the Good Guys. Sure, the world is unpredictable, stochastic — hence the need for a probabilistic approach to assessing political and human affairs. But liberals, progressives, Democrats — whatever you wanted to call us — at least we were trying to get the right answer rather than succumb to the sort of postmodern relativism that [Karl] Rove engaged in. We stood for Facts, Data, Empiricism: reality was on our side. . .

The moment the Good Guys act like they have all the right answers — and that they are even entitled to tell “noble lies” when it suits the public interest — is when they start to become hard to distinguish from the bad guys.

Coming next in the series: Baselines for detection, why they matter and what they tell us.

This post was originally published on Roger’s Substack, The Honest Broker. If you enojyed this piece, please consider subscribing here.

1 A new paper out just today argues with respect to disasters (not weather): “For all disaster types investigated, the long-term (multi-decade) true number of disasters appears to be unexpectedly stable over time” and singles out Munich Re the Asian Development Bank and the World Meteorological Organization for spreading false claims.

2 The careful reader will note that this series has thus far emphasized the detection of change. In coming posts, I’ll have more to say on attribution.

3 Here is the original Table 12.12.