In the U.S. presidential debate earlier this week, the Democratic nominee Kamala Harris offered a strong endorsement of not just the technology of fracking but also of fossil fuels:

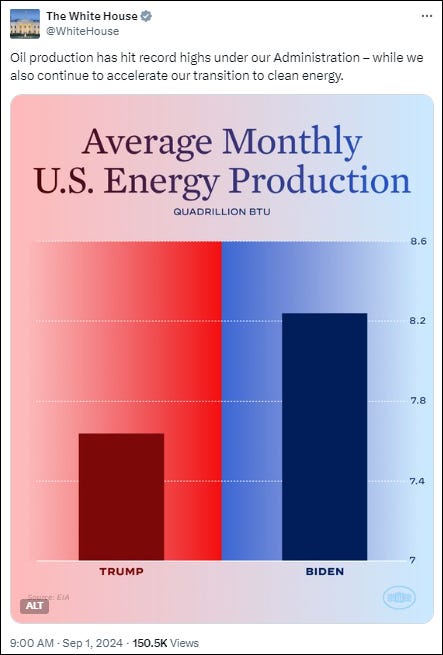

I was the tie-breaking vote on the Inflation Reduction Act, which opened new leases for fracking. My position is that we have got to invest in diverse sources of energy so we reduce our reliance on foreign oil. We have had the largest increase in domestic oil production in history because of an approach that recognizes that we cannot over rely on foreign oil. . . I am proud that as vice president over the last four years, we have invested a trillion dollars in a clean energy economy while we have also increased domestic gas production to historic levels.

Harris comments at the debate marked a significant change from her stance on fracking when running for the 2020 nomination:

I’m committed to passing a Green New Deal, creating clean jobs and finally putting an end to fracking once and for all.

It is not unusual for politicians to change their policy views, particularly as they move from the idiosyncrasies of party primaries to the broader dynamics of a general election. In this instance, Harris’ volte face on fossil fuels appears to reflect a new-found sobriety among Democrats about the realities of energy, the economy, and geopolitics.

Consider this remarkable exchange last night on CNN between Van Jones — a Kamala Harris supporter and former Obama Administration official responsible for “green jobs — and the CNN anchor, Abby Phillip:

Van Jones: Kamala Harris needs fracking. . . Why does she need it? Fracking is giving us a geopolitical weapon against Putin. The reason that we’ve been able to hold the European coalition together is because when Putin said, if you back Ukraine, I’m going to cut gas off to Europe. I’m going to freeze Europeans in their beds. The United States said, no, you’re not. You know why? We are now the biggest exporter of natural gas in the world. We sent a liquid natural gas to Ukraine and where did it come from? It came from fracking in Pennsylvania. So, Pennsylvania fracking is key to our geopolitical strategy. . .

Abby Phillip: Van Jones sitting here at this table with his history of environmental issues, defending fracking, is not something I had on my bingo card . . .

Van Jones: Early on in my career, we thought we were going to be able to get all the way to our clean energy goals with no fossil fuels. It turned out that wasn’t true. It turned out you’re actually going to have to have a more robust mix. The entire party came to that conclusion four years ago. So, people keep pointing back to ideas that I had and others had that turned out to be non-workable ideas. But in practice, in California and other places, the party has matured. It’s not just Kamala Harris.

These comments stand in stark contrast to Jones’ earlier views — In his 2008 book, The Green Collar Economy, Jones invoked peak oil while arguing for a rapid cessation of fossil fuel production and consumption:

Fossil fuels are a finite resource doing infinite damage. As long as we rely on fossil fuels to power our society, our economy is at risk for stagflation — and our planetary home is at risk.

The changing views of Harris and Jones reflect fundamental realities of energy policy, which I have tried to describe as a four-legged stool. It is in our common interests — nationally and globally — to have more energy access and security and less energy costs and impacts.

Energy politics is typically characterized by groups who emphasize a subset of these four objectives, which has the seeming advantage of hiding important tradeoffs, but the disadvantage of being disconnected from reality. Ignoring reality is easy for keyboard warriors and single-issue advocates — but it is not a viable path to electoral success for national politicians charged with serving common interests and getting a majority of votes.

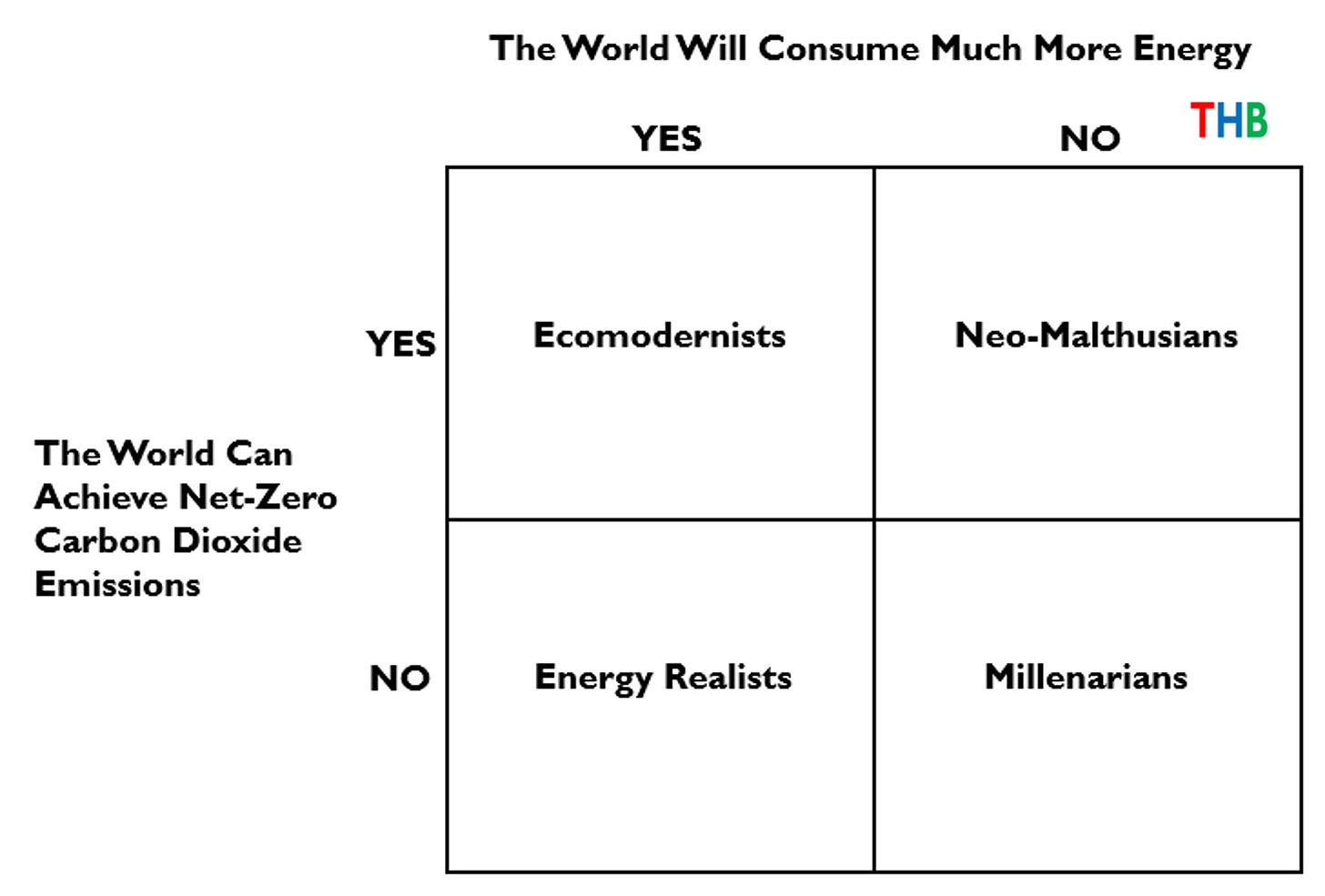

A while back, I suggested that energy and climate policy positions could be characterized by a simple two by two matrix, shown below.

Here is how I describe each quadrant:

- Millenarians. These include groups such as Extinction Rebellion and Just Stop Oil. Some believe that the end is nigh and that we need to starting building our bunkers. When politicians speak of climate change as an “existential threat” or a “climate emergency” they are giving a nod to those who view the issue in apocalyptic terms.

- Neo-Malthusians. These include degrowthers, neo-colonialists who wish to limit energy in poor countries, and the old-school population control crowd. They see limiting population and the economy as central to achieving net-zero, invoking very similar arguments to Malthusians whose concerns about too many people long predated concerns about climate change.

- Energy Realists. These folks look at rates of decarbonization of the global economy consistent with achieving net zero carbon dioxide and judge pessimistically that it cannot be done (or cannot be done this century), while at the same time acknowledging humanity’s seemingly insatiable appetite for energy. Some dismiss climate change altogether.

- Ecomodernists. These are people (like myself) who look at the history of innovation in areas such as agriculture and health and optimistically believe that similar incredible technological gains can be made in energy systems over the 21st century, moving us systematically towards net-zero, global energy access, and with cheaper and secure energy.

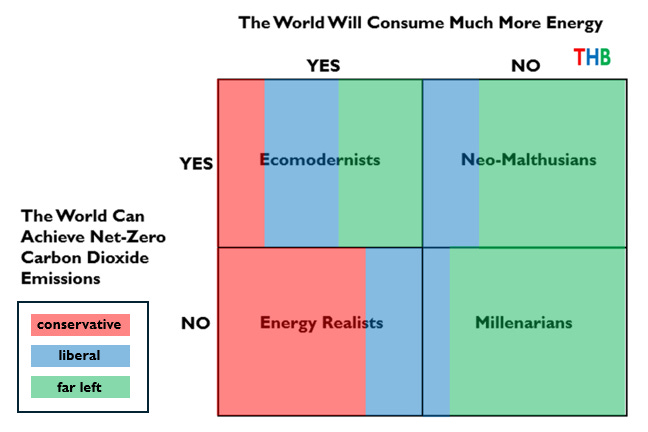

I have been thinking about these categories this week as I have tried to make sense of the Democrats remarkable turn towards embracing fracking and fossil fuels. The image below offers my qualitative, first draft of how American politics might map onto the four categories, helping to explain the political calculus that underlies the changing views of Democrats.

The neo-Malthusians and Millenarians, despite their relatively much smaller overall numbers, have for many years had an outsized influence on U.S. energy and climate politics mainly through their sway with Democrats who went through a period of apparently thinking that these constituencies offered a viable path to electoral success. Democrats appear to be shaking off these views and their capture by the far left — and not a moment too soon.

Energy Realists often emphasize three legs of the stool, but at times neglect or dismiss the fourth leg — impact, including the risks posed by climate change. Even so, there is a lot of common ground between Energy Realists and Ecomodernists.

This leads me to the conclusion that, in a U.S. context at least, Ecomodernism offers the most politically viable stance with respect to energy and climate policy, because it explicitly recognizes all four legs of the stool.

In the debate earlier this week, Vice President Harris sounded a lot like an Ecomodernist:

I am proud that as vice president over the last four years, we have invested a trillion dollars in a clean energy economy while we have also increased domestic gas production to historic levels. We have created over 800,000 new manufacturing jobs while I have been vice president. We have invested in clean energy to the point that we are opening up factories around the world. . . And I’m also proud to have the endorsement of the United Auto Workers and Shawn Fain, who also know that part of building a clean energy economy includes investing in American-made products, American automobiles. It includes growing what we can do around American manufacturing and opening up auto plants . . .

Vice President Harris and the Democrats have a huge opportunity to run with their new-found embrace of an all-of-the-above energy strategy as being central to the economy, national security, and environmental goals. Let’s see if they take it.

This post was originally published on Roger’s Substack, The Honest Broker. If you enjoyed this piece, please consider subscribing here.