Networks shape modern life. From roads to the internet to global supply chains, they enable movement, exchange, and value creation. But networks also suffer from congestion, a problem driven by both physical limitations and the difficulty of defining and enforcing property rights. In some networks, pricing mechanisms can help mitigate congestion, but political and regulatory constraints often prevent the use of dynamic or high enough prices to do so effectively. Another solution is expansion—building more capacity. Yet the incentives to make those investments are often weak, misaligned, or outright obstructed. Nowhere is this paradox more evident than in electricity transmission, the high-voltage backbone of the power system.

In this series on regional transmission organizations (RTOs), I’ve been exploring how they function as wholesale power market platforms. RTOs carry a dual mandate: they operate market platforms for trading the various products and services required to deliver bulk power (day-ahead energy, real-time energy, a set of ancillary services for voltage and frequency regulation), and they manage the transmission grid to meet reliability standards. So far I’ve examined the path dependence of RTO membership and governance, the continued influence of historically vertically integrated utilities, and the basics of transmission regulation and investment incentives. Transmission remains one of the most vexing economic and engineering challenges in electricity markets. Today, I’ll examine why large-scale, high-voltage transmission projects remain scarce despite clear economic and environmental benefits, and I’ll highlight two important recent studies that shed light on the issue.

The Role of Transmission in Wholesale Power Markets

Transmission is the transportation network for electricity, and like any transportation system, congestion is costly. The complexity of the high-voltage alternating current (AC) grid means that the location of generation and demand at any given moment determines both physical grid operations and market outcomes. To manage congestion, organized wholesale markets in the U.S. rely on locational marginal pricing (LMP), which reflects the marginal cost of delivering electricity to different locations. But as demand rises and the generation mix shifts toward renewables, LMP signals alone are insufficient to drive needed transmission expansion, particularly in light of price caps in power markets that constrain LMPs when the grid is stressed.

The rapid growth of renewable generation, especially wind power, has exacerbated transmission bottlenecks. Investment in transmission can come from two sources: regulated utilities or independent developers. Theoretically, independent transmission developers should be able to step in to address congestion and expand capacity. In practice, they face a regulatory and institutional gauntlet that often makes investment infeasible.

Why Independent Transmission Investment Struggles

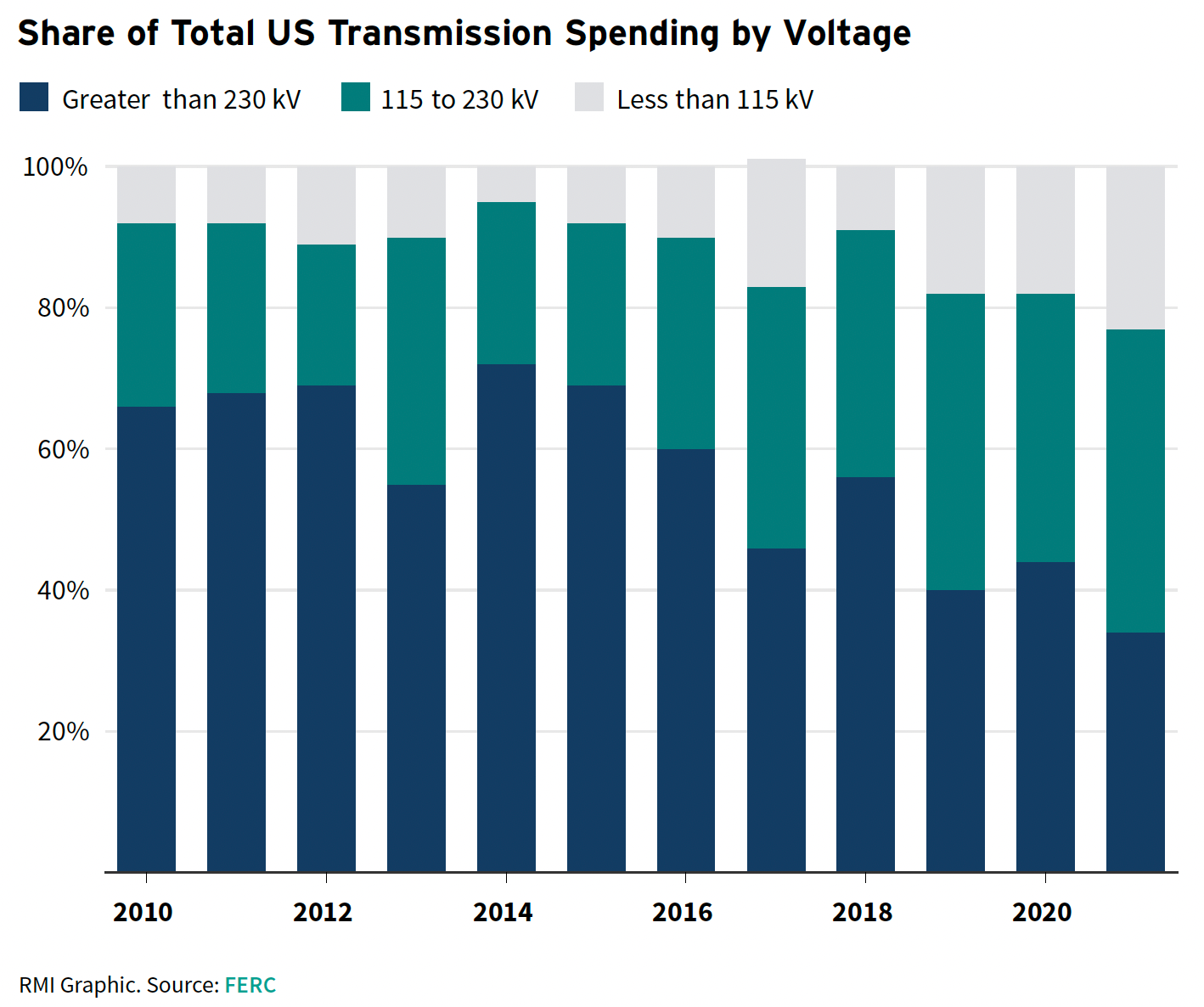

Unlike generation, which operates in competitive markets in much of the U.S., transmission remains largely under the control of regulated utilities. These utilities have both the incentive and the means to block independent projects that could compete with or reduce the value of their own transmission assets. Right of first refusal (ROFR) provisions—often enshrined in state law—allow utilities to sideline independent developers, reinforcing the dominance of incumbent firms. Even when ROFR is removed, utilities favor intrastate, lower-voltage transmission projects that serve their own needs over regional, high-voltage projects that would enhance broader market efficiency.

The regulatory landscape complicates investment further. Transmission planning and cost allocation processes—often controlled by utilities—tend to prioritize utility-led projects. Independent developers struggle to recover their investment costs under these rules, discouraging private capital from entering the market. Multi-state projects face overlapping jurisdictional hurdles, making regulatory approval a slow and uncertain process.

As Russell Gold described in Superpower, Michael Skelly’s attempt to develop a privately funded transmission network to move wind power across the country was stymied by entrenched utility resistance, regulatory roadblocks, and the absence of clear financing and approval mechanisms. The same structural barriers continue to deter private investors, leaving the transmission system underbuilt and ill-equipped to support the energy transition.

FERC Order No. 1000: A Reform That Fell Short

Recognizing these barriers, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) attempted to introduce competition into transmission development with Order No. 1000 in 2011. The order required public utility transmission providers to engage in regional planning, consider state and federal policy goals, eliminate ROFR for federally regulated projects, and establish transparent cost allocation methods.

In theory, these changes were meant to foster competition and improve cost efficiency. In practice, implementation has been sluggish and uneven. Utilities have found ways to circumvent competitive processes, often by classifying projects as “reliability” upgrades that are exempt from competitive bidding. State legislatures have also stepped in, reinstating ROFR laws that undercut FERC’s intent. As a result, transmission investment remains fragmented, favoring local projects that entrench incumbent advantages rather than regional projects that could improve market access and efficiency.

The Market Power Problem in Transmission

A deeper, more persistent incentive issue compounds the problem. Many utilities, especially those still vertically integrated with both generation and transmission, benefit from the status quo. Even in restructured states, where generation and transmission are functionally unbundled, utilities with affiliated generation companies retain financial incentives that distort transmission planning. I’ll have more to say about research on this case next week.

Expanded high-voltage transmission can threaten utilities that own generation assets by increasing competition and reducing congestion rents. Transmission constraints often raise LMPs in certain areas, generating higher revenues for utilities with generation in those constrained zones. Large-scale, high-voltage transmission expansion erodes those rents by enabling cheaper, more efficient, and often renewable generators to reach demand centers. This revenue dynamic is one reason why utilities have stronger incentives to invest in intrastate, lower-voltage transmission, which benefits their own generators while maintaining existing barriers to generation competition.

Empirical Evidence on Transmission Investment Challenges

Two recent research papers provide empirical insight into these issues.

The first is an extensive and thorough empirical analysis from University of Michigan economist Catherine Hausman. Her NBER working paper, Power Flows: Transmission Lines, Allocative Efficiency, and Corporate Profits, examines the economic inefficiencies caused by transmission congestion in the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO) and the Southwest Power Pool (SPP), using hourly data 2016-2022.

Hausman estimates the costs of transmission constraints, evaluates the distributional effects on firms, and explores the political economy implications of transmission planning. But that summary does injustice to her analysis, which is remarkable. First she uses hourly generator data to estimate each thermal (coal, natural gas, etc.) generator’s marginal cost under a series of counterfactual scenarios starting with least-cost dispatch without transmission constraints, and then with transmission constraints. She compares those counterfactuals to actual prices, generator quantities, and wind power curtailment to estimate the welfare losses arising from transmission congestion. She estimates that congestion-related inefficiencies exceeded $2 billion in 2022, driven by rising wind curtailments and increasing reliance on high-cost fossil generation in constrained areas.

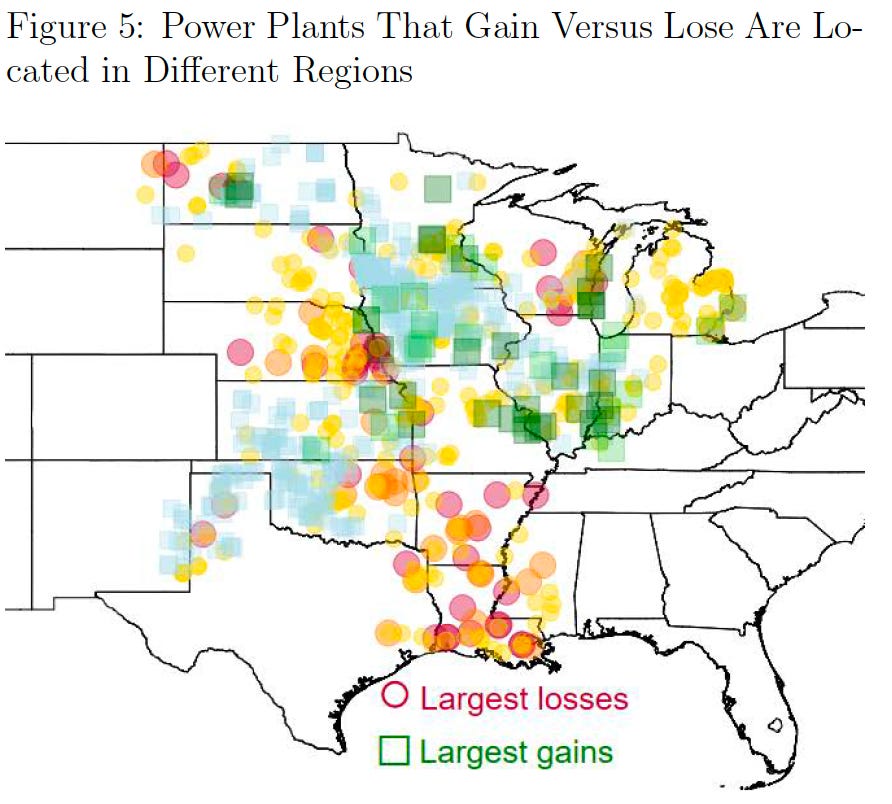

Using this counterfactual analysis, she finds that eliminating transmission constraints would significantly lower costs by enabling more efficient dispatch. However, utilities with fossil generation assets in constrained areas stand to lose revenue if congestion is reduced. The four firms with the most to lose from full market integration would have seen a collective $1.6 billion revenue decline in 2022.

Source: Hausman (2024)

Hausman documents how utilities strategically obstruct transmission expansion, whether by delaying planning processes, lobbying against regional projects, or even hiring consultants to pose as concerned stakeholders in regulatory proceedings. A case study of Entergy, a vertically integrated utility operating in MISO South, illustrates how an incumbent firm can manipulate the transmission planning process to preserve its market power. Entergy has been accused of obstructing transmission development that would have increased competition from independent generators and lowered wholesale prices in its service territory. Her findings underscore the role of incumbent financial interests in maintaining inefficient congestion. Even when new infrastructure would generate aggregate economic benefits, entrenched interests can delay or block projects that threaten their financial position

The second paper, Mind the Regulatory Gap from RMI, examines how U.S. transmission investment has shifted away from regional projects in favor of local transmission spending. RMI highlights how the lack of oversight for local transmission projects allows utilities to sidestep competitive planning, leading to costlier and less effective investments. In PJM, for example, local transmission spending grew from 9% of total investment in 2005–2013 to 73% in 2014–2021, even as high-voltage regional transmission miles declined. Similar trends are evident in MISO (as discussed in the Hausman paper), ISO New England, and CAISO, where local projects now account for the majority of new transmission investment.

RMI attributes this trend to a “regulatory gap”: regional transmission projects face stringent planning and cost allocation scrutiny, while local projects proceed with minimal oversight. This structure incentivizes utilities to prioritize lower-voltage projects that reinforce their market position rather than regional infrastructure that could integrate more renewables and lower costs for consumers.

Conclusion

A decade after Order 1000, independent transmission investment remains rare, and regional transmission development is still not happening. Utilities continue to prioritize local projects that maximize their financial returns while suppressing competitive regional transmission development. The result is a system that is less efficient, more expensive, and poorly equipped to handle growing electrification and clean energy deployment.

Addressing these challenges requires regulatory reform that realigns incentives. Stronger federal oversight of transmission planning, cost allocation, and competitive processes could reduce barriers to independent investment, but that shift would challenge the existing split of jurisdiction and power between federal and state regulators.

My next post in this series will grapple with the “so what do we do?” question that naturally arises. A hint: regulatory reform.

This article was originally published on Lynne’s Substack, Knowledge Problem. If you enjoyed this piece, please consider subscribing here.