For this first edition of THB Subscriber Questions (THBSQ#1) I am going to address one question asked by many readers.

Anders Valland asks:

Professor, now you know where it starts. What are your reflections on the new tariff regime?

I’ll start with a disclaimer and some throat clearing — I do not research or publish in international trade. My PhD is in political science and my areas of specialization were public policy, American politics, and quantitative methods, with a fair bit of economics courses along the way. With that, caveat lector . . .

What is the problem that Trump’s trade policy seeks to address?

In policy analysis, before talking about policy options it is absolutely essential to understand the problem that the policy is supposed to address. A problem is simply a perceived difference between current conditions and some preferred situation. Getting from current conditions to the preferred situation depends upon actions that cause current conditions to move to the preferred situation.

Different people will have different perceptions of the nature of problems or whether a problem requiring intervention even exists at all. Problem definition is therefore an exercise in politics.1 Problems do not exist out there in the real world, we define them.

That gives us two questions to ask of the justification put forward for any policy:

- What is the preferred situation and the current condition?

- What caused the gap between the two?

To answer these questions, let’s take a close look at the Trump Administration’s Executive Order (EO) issued yesterday — Regulating Imports with a Reciprocal Tariff to Rectify Trade Practices that Contribute to Large and Persistent Annual United States Goods Trade Deficits.

What is the preferred situation and current state?

The stated goal of Trump’s trade policy is to increase U.S. manufacturing output:

Both my first Administration in 2017, and the Biden Administration in 2022, recognized that increasing domestic manufacturing is critical to U.S. national security. According to 2023 United Nations data, U.S. manufacturing output as a share of global manufacturing output was 17.4 percent, down from a peak in 2001 of 28.4 percent.

Over time, the persistent decline in U.S. manufacturing output has reduced U.S. manufacturing capacity. The need to maintain robust and resilient domestic manufacturing capacity is particularly acute in certain advanced industrial sectors like automobiles, shipbuilding, pharmaceuticals, technology products, machine tools, and basic and fabricated metals, because once competitors gain sufficient global market share in these sectors, U.S. production could be permanently weakened. It is also critical to scale manufacturing capacity in the defense-industrial sector so that we can manufacture the defense materiel and equipment necessary to protect American interests at home and abroad.

A first question to ask is what does it mean to “increase U.S. manufacturing output”?

Is an increase to be measured in absolute terms, that is, measured in dollars? Or is it a relative share, such as measured as a proportion of U.S. or global GDP?

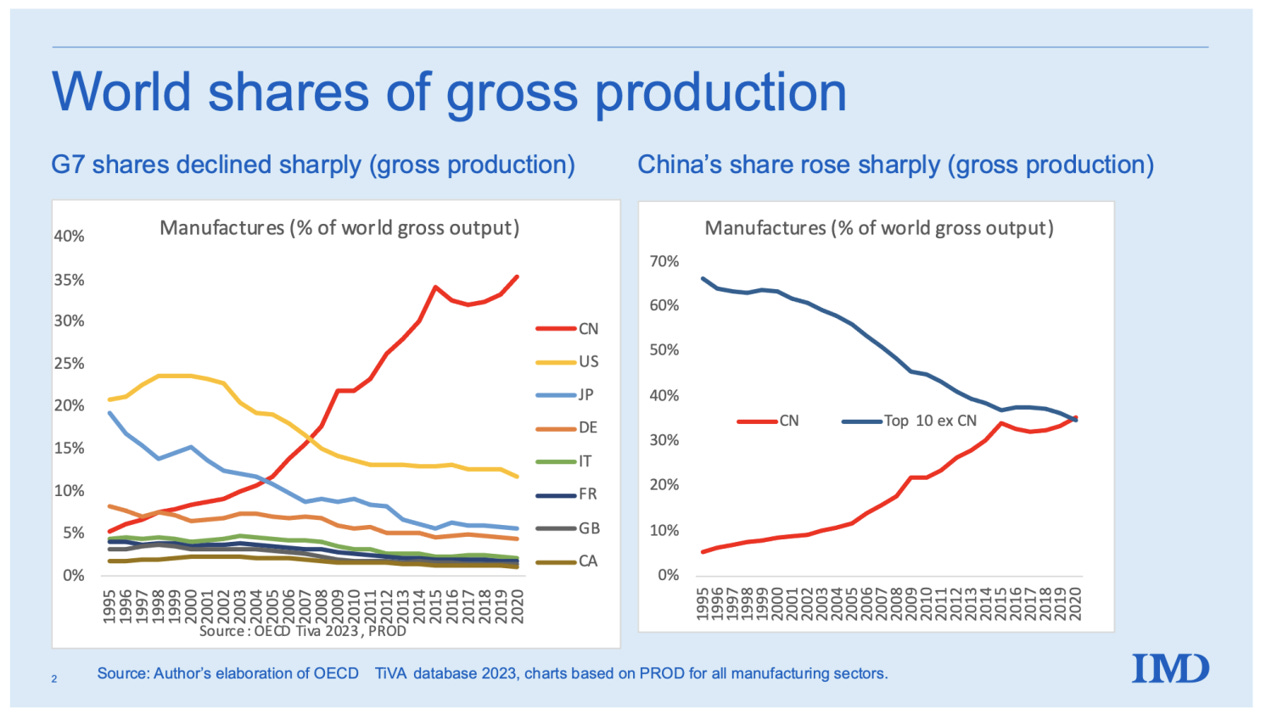

The EO points specifically to a decline in the U.S. manufacturing share of global GDP to indicate the “decline” in output. That assertion is correct, as you can see in the figure below, with the U.S. share in yellow in the left pane.

The figure also shows that every country with significant manufacturing saw a decline of output as a proportion of GDP over the past three decades, except one — China — which today has output greater than the total output of the next 10 greatest manufacturing nations.

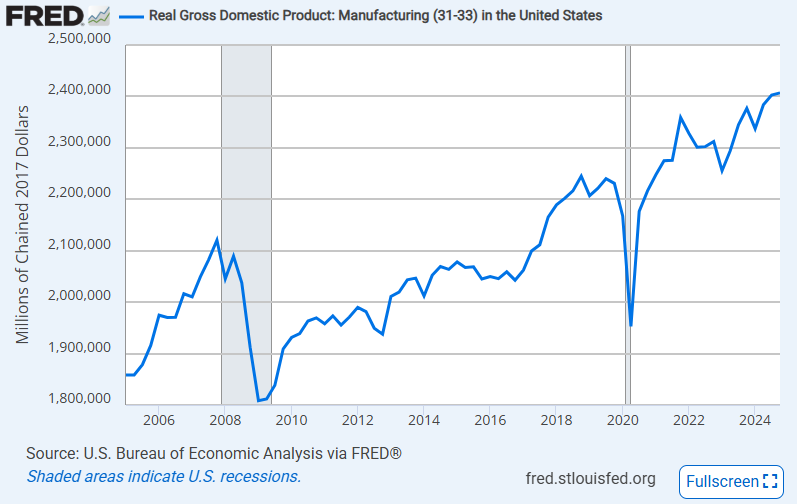

Alternatively, if we look at U.S. manufacturing in terms of output measured in dollars (inflation-adjusted), shown below, we see a very different picture.

These data show that in absolute terms, there has been no decline in U.S. manufacturing — Output has increased substantially over the past 20 years, punctuated only by the Global Financial Crises and COVID-19.

So my first critique of the Trump trade policy is that it is totally unclear on the nature of the problem to be addressed. The relative decline of U.S. manufacturing in the global context has everything to do with China’s increasing role — everyone else saw a decline as well.

So what is the specific policy goal of the Trump trade policy?2

Is it to increase U.S. manufacturing in absolute (dollar) terms? If so, then what does success look like? A 10% increase from 2024? 20%? 100%? No one knows the answer to this question because the Trump administration does not give one.

Alternatively, is the goal to increase the share of manufacturing in the U.S. and/or global economy? Again, no one knows the answer to this question either because it has not been articulated.3

Beyond the stated objectives written in the EO, President Trump and his appointed officials have offered other characterizations of the problem to be addressed, For instance, President Trump in announcing the EO yesterday, said the problem was actually “fairness”:

“Our country and its taxpayers have been ripped off for more than fifty years, but it is not going to happen anymore. It’s not going to happen. In a few moments, I will sign a historic executive order instituting reciprocal tariffs on countries throughout the world. Reciprocal. That means they do it to us and we do it to them. Very simple. Can’t get any simpler than that.”

In his delivered remarks, the only nod given to manufacturing was with respect to “manufacturing jobs,” which suggest another possible aim of trade policy. The EO states:

The decline of U.S. manufacturing capacity threatens the U.S. economy in other ways, including through the loss of manufacturing jobs.

This claim is not true. As the figure shows above, U.S. manufacturing capacity has increased, even as total jobs have decreased, due to gains in productivity and automation. Increasing manufacturing jobs may or may not be a good idea, but the Trump EO does not articulate how trade policy addresses the number of jobs or what success might look like.

If the Trump EO was submitted as an assignment in one of my advanced policy courses, I’d hand it back and say, you need to do a lot more work in defning the problem, as this does not yet make much sense.

What caused the gap between the current and desired state?

The lack of clarity in the aims of Trump’s trade policy are countered by clarity in how the EO identifies the source of the problems that they think exist:

Large and persistent annual U.S. goods trade deficits have led to the hollowing out of our manufacturing base; inhibited our ability to scale advanced domestic manufacturing capacity; undermined critical supply chains; and rendered our defense-industrial base dependent on foreign adversaries. Large and persistent annual U.S. goods trade deficits are caused in substantial part by a lack of reciprocity in our bilateral trade relationships.

Here then is the asserted causal chain:

Lack of reciprocity in bilateral trade —> U.S. goods trade deficits —> hollowing out of manufacturing

With a clear picture of cause and effect, policy options then come into view. The policy logic here appears to be: Create reciprocity in bilateral trade which will eliminate U.S. goods trades deficits which will in turn increase U.S. manufacturing.

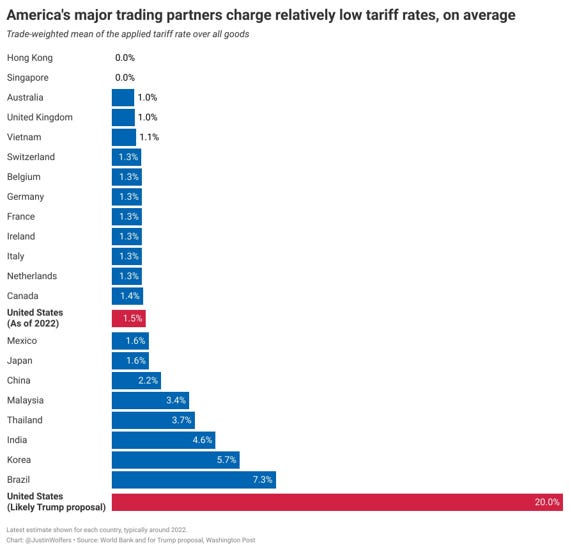

Thus, the first step in this chain is to create reciprocity in bilateral trade, which the Trump administration argues will result from “reciprocal tariffs.” However, the tariffs being implemented are not in fact reciprocal.

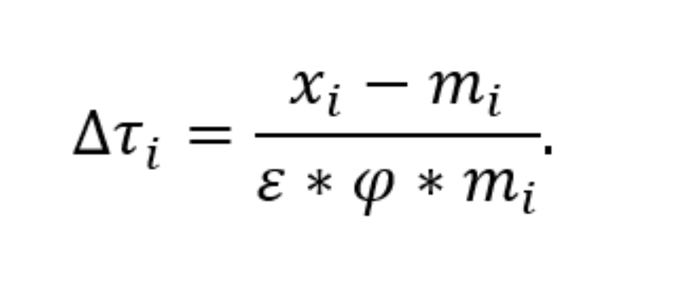

The actual logic behind the tariffs was described by the administration to Yahoo News as estimated (using the simple formula above),

by computing the tariff level consistent with driving bilateral trade deficits to zero.

Read that again.

The Trump administration thus has departed from their own policy logic where a lack of reciprocity in tariff regimes was supposed to be driving trade imbalances. The implemented tariffs indicate that trade balances are much more complicated than the actual small tariffs in most situations, as you can see below.

In policy we often have to be on the lookout for goal substitution — when means become ends, and we forget why we were implementing the policy in the first place. That seems to be happening here — a goal of fixing U.S. manufacturing (whatever that means) appears to have been displaced by a goal of eliminating trade deficits with all countries.

Alternatively, it could be that the real policy goal here is to eliminate trade imbalances and the stuff about manufacturing is insincere. When means become ends, it becomes fair to question the stated goals used to justify policy, and whether there may be unstated goals in play.

What is clear is that the policy logic articulated by the Trump Administration does not match up with the proposed policies supposedly following that logic. That is even before we get to the actual economic merit of the proposed policies, which don’t make any sense either. But I’ll leave that to economists to explain.

For last words today, here is Tyler Cowen at The Free Press:

This is perhaps the worst economic own goal I have seen in my lifetime. I cannot think of any credentialed economist colleague—Democrat, Republican, or independent—who would endorse it.

This post was originally posted on The Honest Broker. If you enjoyed this piece, please consider subscribing here.

1 Problem definition was always one of my favorite graduate seminars. Here is an old syllabus still online for one of my graduate seminars.

2 Note that this is a technical question of policy analysis — The answer here cannot be to “make American great again” or “stop being ripped off.” Those are slogans, not policy goals.

3 Setting aside Constitutional obligations, one reason why Congressional involvement in policy making matters is that such details are often discussed openly in the legislative process and ultimately in legislation.