Climate scenarios are fundamental to climate research and policy. For more than a decade, one scenario dominated research informing discussions of climate among scientists and decision makers. Called RCP8.5, today that scenario is widely recognized as implausible, leading to apocalyptic portrayals of future climate change and providing an unreliable basis for policy analyses for adaptation and mitigation.1

Remarkably, the climate science community appears to be on the brink of repeating the folly of RCP8.5, with a new extreme scenario that will be used in “thousands of research papers” and serve as the “foundation of major parts of IPCC assessments.”2 As was the case with RCP8.5, the new family of climate scenarios will be released with absolutely no formal evaluation of their plausibility or feasibility.

This is simply scientific malpractice for a field justified by its relevance to policy.

The family of six proposed new scenarios has been developed by a small group of mainly U.S. and European scientists in a group called the Scenario-Model Intercomparison Project (Scenario-MIP). The Scenario-MIP is part of a larger international project focused on Earth system modeling.

Many people will be surprised to learn that the priorities of a small research community are driving the invention of scenarios that will be the basis of climate research and assessment that underlies major policy decisions around the world.

ScenarioMIP explains its purpose:

The primary purpose of the ScenarioMIP scenarios is to provide emissions and land use pathways to drive ESMs [earth system models]. ScenarioMIP will produce these pathways based on plausible, internally consistent socio-economic and technological scenarios.

The key consideration here is plausibility, which ScenarioMIP defines as follows:

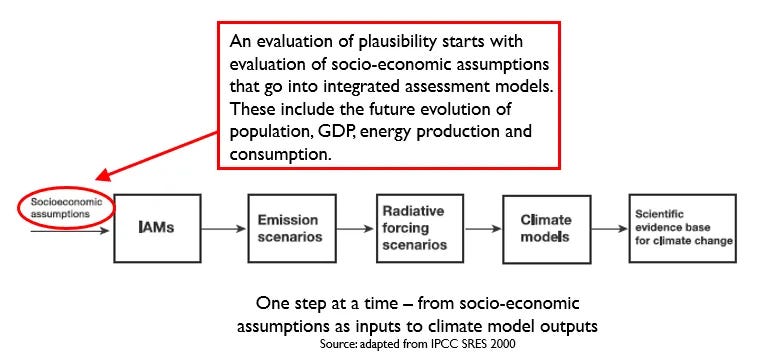

A plausible scenario encompasses a range of outcomes that have a non-negligible likelihood of occurring (see Carter et al., 2007) thus implausible scenarios have a negligible likelihood of occurring. Plausibility is a subjective judgment that can be based on a number of criteria. As such it is useful to compare it to the related concept of feasibility. Feasibility is typically used to describe the potential for an action to occur and is therefore more closely associated with scenarios deriving from a given course of action. However, despite the subtle differences between the two terms, when making judgments about plausibility we can borrow as criteria the multiple dimensions of feasibility identified in IPCC assessments: geophysical, technological, economic, sociocultural and institutional (Brutschin et al. 2021; Riahi et al. 2022; Jewell and Cherp 2023; Ju et al. 2023; Allen et al. 2018b). In other words, for a scenario to be plausible, it should be feasible based on the 5 dimensions mentioned above.

With this definition we should expect then that ScenarioMIP has subjected its new scenarios to an evaluation of plausibility with respect to the five dimensions of feasibility — geophysical, technological, economic, sociocultural and institutional — prior to their approval and release to the world.3

Well, no.

The new scenarios — scheduled to be released in the coming weeks or months — have been created with no apparent evaluation of their plausibility. The failure to take plausibility seriously was behind the RCP8.5 debacle, as Justin Ritchie and I explained in depth in our analysis of how RCP8.5 came to dominate climate research and policy. RCP8.5 was never plausible and never should have been the focus of climate research, much less.

A priority for climate modelers is extreme scenarios, as they are useful in model-based research. ScenarioMIP explains:

ScenarioMIP wants to run plausible scenarios and therefore wants to run the highest plausible scenario.

However, with no formal assessment of plausibility, the “highest plausible scenario” gets identified based on unknown factors, under the community’s priority to utilize the most extreme scenario possible.

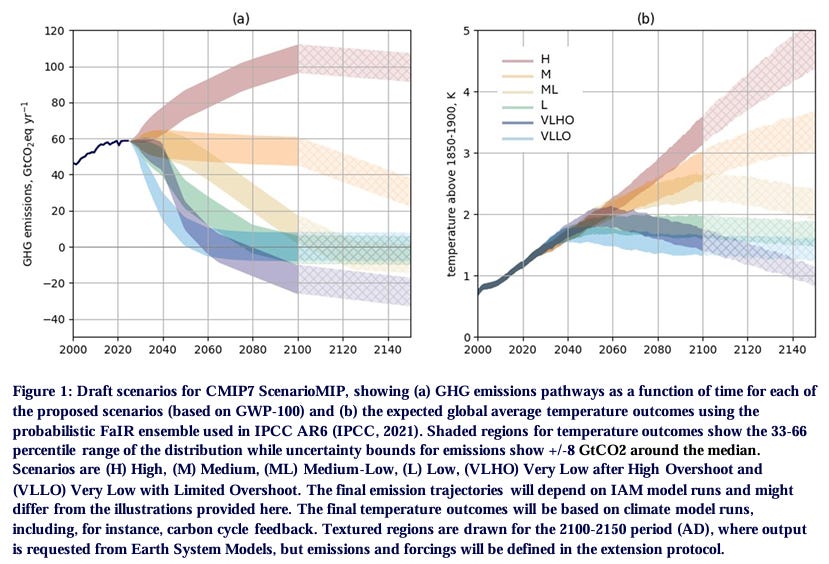

The proposed new scenarios can be seen in the figure below from a new preprint authored by ScenarioMIP.

The most extreme scenario has greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2100 (left panel) of about 110 gigatonnes carbon dioxide equivalent. The panel on the right shows that scenario leads to about 3.5 degrees Celsius by 2100. I’ll call that scenario HIGH, following the figure caption.

ScenarioMIP explains of HIGH:

A scenario based on assuming developments that could lead to high emissions, including, e.g., high demographic growth and slow development of mitigation technologies and diffusion. This high emission scenario is, however, expected to result in forcings below SSP5-8.5.4

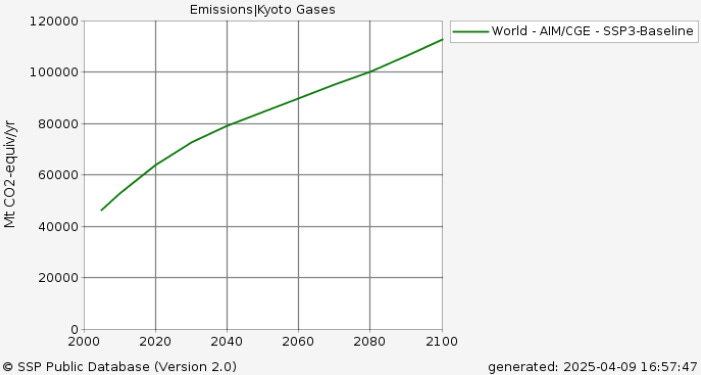

We can dig a little deeper and identify what socio-economic assumptions might underlie the HIGH scenario. In terms of overall emissions, HIGH closely resembles a scenario from the outdated family of scenarios call the Share Socioeconomic Pathways or SSPs.5

The figure below shows the GHG emissions of SSP-7.0 (where the 7.0 represents the level of radiative forcing in 2100), which exceed 110 gigatons carbon dioxide-equivalent in 2100.

You can see that the GHG emissions of SSP3-7.0 closely approximate those of HIGH.6

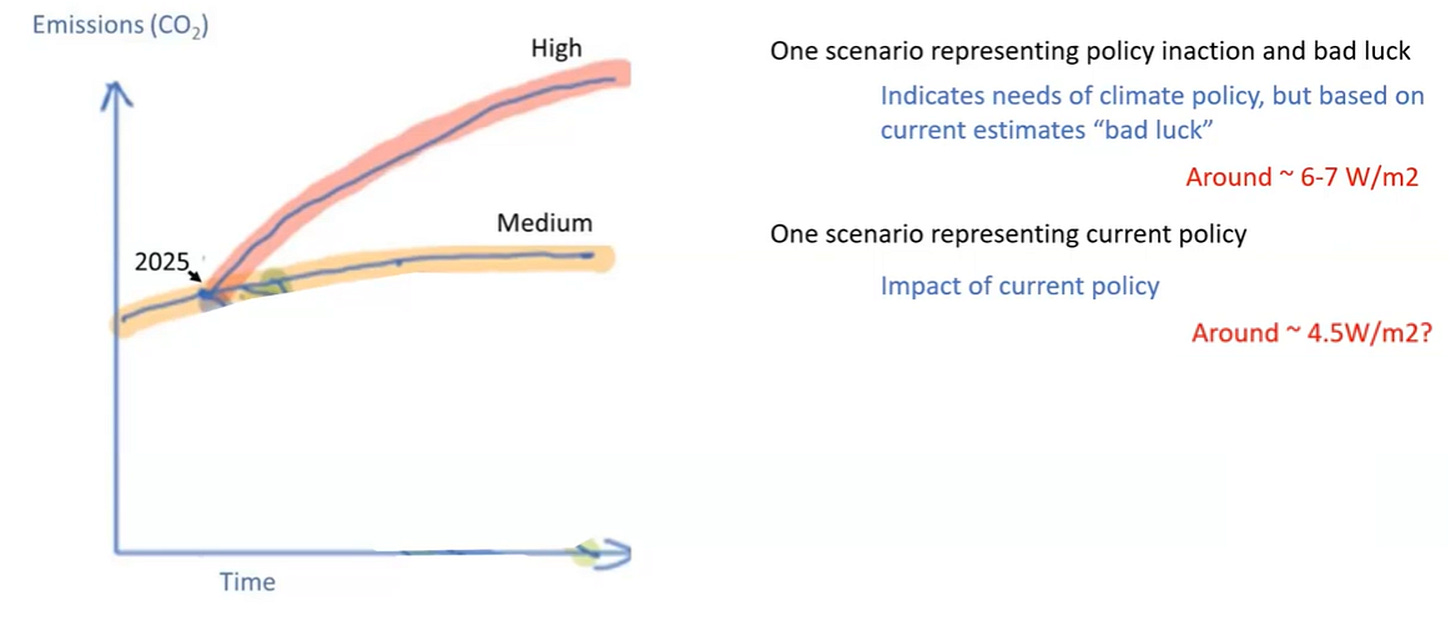

Indeed, in a presentation anticipating the new scenarios, one of its main architects associated the HIGH scenario with a radiative forcing of 6 to 7 Watts per meter-squared, as you can see below in a slide from his presentation. The world is currently undershooting a RCP4.5 scenario, which we’ve known for a while, which sits below the mock-up of the medium scenario in the image below..

Is 6 or 7 Watts per meter-square radiative forcing in 2100 consistent with any set of plausible socio-economic assumptions? No one knows because that question has not been addressed by ScenarioMIP.

ScenarioMIP explains that such an evaluation is a task for others to take on later (emphasis added).

The SSPs continue to be in wide use and recently the demographic and economic drivers for these scenarios have been updated. However, other storylines and drivers could be adopted or created as a basis for the ScenarioMIP emissions and land use pathways. In this proposal, we remain agnostic about the socio-economic pathways ultimately used in producing the emissions and land use pathways with IAMs [integrated assessment models].

The notion that the climate modeling community should identify emissions scenarios and then, later, integrated assessment modelers should “ultimately” come up with plausible assumptions to justify the assumed emissions gets things exactly backwards.

There are good reasons to think that a doubling or tripling of greenhouse gas emissions this century are not plausible. In a paper offering advice to the ScenarioMIP, one group of scenario experts called SSP3-7.0 a “hypothetical backdrop scenario” that might be used to illustrate an imaginary world where emissions increased dramatically through the 21st century.

In comments on the ScenarioMIP preprint announcing the new scenarios, climate scientist Jean-François Lamarque questioned the plausibility of the HIGH scenario:

The end result is still with a high RCP8.5-like (or close) scenario. So, were the critiques unfounded and/or ignored? . . . Looking at Fig 1a, the upward bend in CO2 emissions for this scenario seems hard to justify, unlike the M [medium] and ML [medium-low] scenarios.

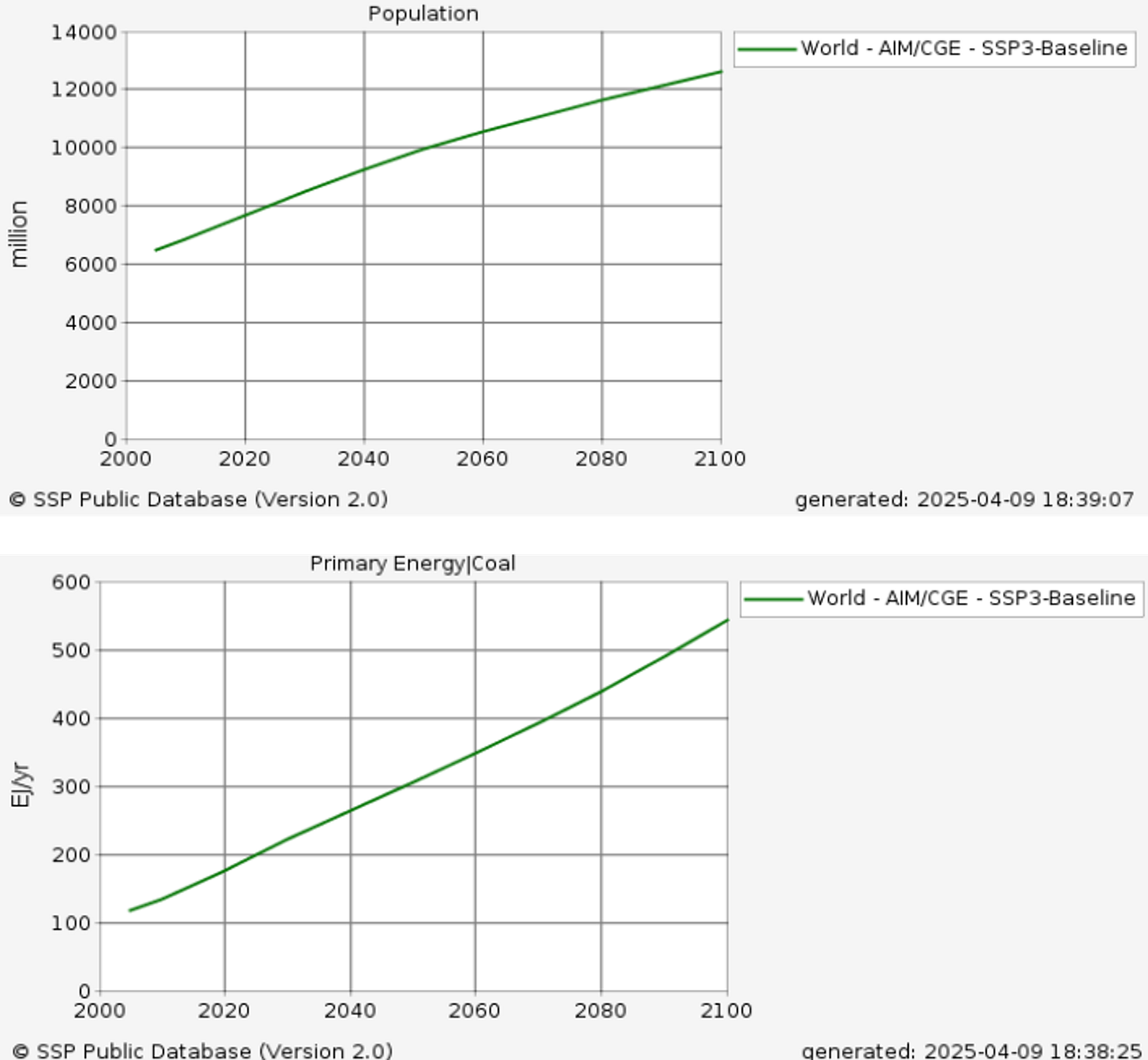

To cite just two examples why we should question the plausibility of a 7.0 W/m^2 radiative forcing scenario — SSP3-7.0 assumes that by 2100 global population will approach 13 billion and that coal consumption will increase five-fold. Neither assumption is remotely plausible in 2025.

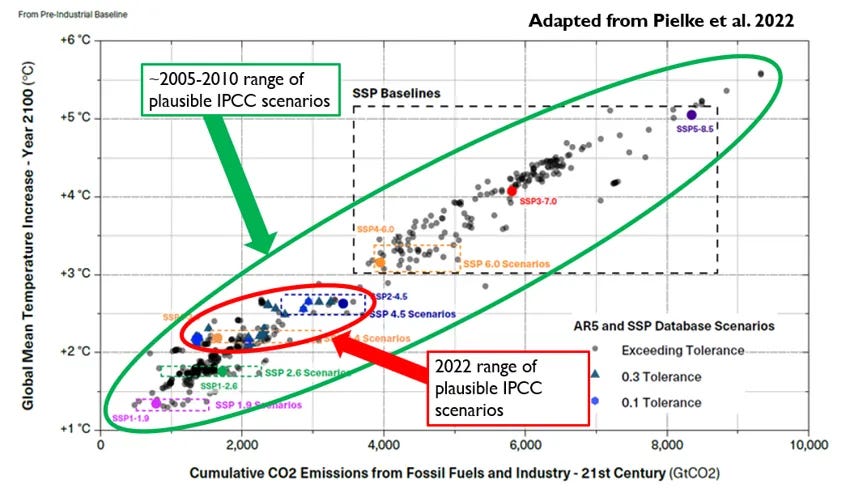

Even a 6.0 W/m^2 level of radiative forcing in 2100 may be implausible, based on our 2022 analysis of scenario plausibility, which is summarized in the figure below.

A radiative forcing of 6 or 7 W/m^2 may or may not ultimately be plausible.7 The issue here is that I don’t know, you don’t know, and more importantly, ScenarioMIP does not know that as they charge ahead with producing the scenarios that will dominate climate science and policy for the next decade or longer.

Last June I asked:

We are on the cusp of having REP-7.0 take over from RCP8.5, with the same negative consequences for research and policy and for the next decade or more. Can we change course before it is too late?

It is now getting very late.

This was originally published on The Honest Broker substack. If you enjoyed this piece, please consider subscribing here.

1 Being widely perceived as implausible has not stopped RCP8.5!

2 Google Scholar returns more than 49,000 papers that have used RCP8.5

3 The ScenarioMIP failure to consider socio-economics has other significant issues as well. Several commenters on their preprint noted that the new scenarios ignore considerations of equity: Nathan Gillett observes: “Overall, the current draft slightly gives the impression that the authors are trying to sidestep equity and justice considerations by arguing that that the physical climate is not very sensitive to these assumptions.” And Akhil Mythri, Tejal Kanitkar, and T. Jayaraman explain that equity outcomes need to be considered in scneario design: “Modeling studies need to be done to clearly demonstrate the influence (or the lack thereof) of socio-economic assumptions on ESM outputs, rather than simply claiming a priori that ESM outputs are insulated from underlying socioeconomic assumptions.” This topic is probably worth its own post.

4 SSP5-8.5 is the updated version of RCP8.5. The 8.5 refers to radiative forcing in Watts per meter-squared.

5 Some comments down in the weeds: The SSP scenarios were intended to replace the RCPs, but never really accomplished that. See Pielke and Ritchie 2021.

6 Worth noting that the temperature outcome of HIGH (~3.5C in 2100) is below that of SSP3-7.0 (~4.0C in 2100). This is a little puzzling as SSP3 has large amounts of air polluiton which reduce temperature increases.

7 Meantime, some in the climate community appear to be laying the groundwork for a HIGH-7.0 scenario. In a post earlier this week climate scientist Zeke Hausfather warned, “The SSP3 world gives a glimpse of what backtracking on climate progress might look like.” That is false.