I was listening to Tyler Cowen’s Conversations With Tyler podcast with Jennifer Pahlka, rich and full of detail relevant to my previous post on the pacing problem. In addition to recommending this good conversation, I echo Tyler’s recommendation of Jen’s book Recoding America: Why Government is Failing in the Digital Age and How We Can Do Better.

Jen used a phrase that piqued my interest, especially as it intersects with my work on the pacing problem: the bureaucratic rigidity cycle. I went down a little rabbit hole, first doing a standard internet search that led me to the work of political scientist and public choice scholar Anthony Downs, best known for his work on an economic theory of democracy. I’m familiar with this work, but not with his earlier work, Inside Bureaucracy (1967). So I asked ChatGPT to tell me about it and his bureaucratic rigidity work, to apply it to electricity, and to compare it to Ostrom’s institutional analysis and design approach.

ChatGPT did a pretty decent job, in part because I have personalized my GPT and it has a history of my writing through the links I have fed it (and the fact that I often use it to edit my writing, although it splits infinitives which I would NEVER DO). I was also struck by some of the connections it made to pressing electricity issues, so at the very least reading its response is thought-provoking if nothing else.

ChatGPT does have a love of bullet lists that I do not share, as I prefer fully-formed sentences connected together to form logical paragraphs. Still, I’m sharing its response without my edits, in part so we can all learn more about Downs’ work and in part to provide an example of how I am finding AI useful as a co-worker in a topic that I know enough about to interpret its content and assess its accuracy reasonably well. Please tell me in the comments if the Downs work is new to you, if you find it insightful, and if ChatGPT’s response is inaccurate or incomplete.

Anthony Downs, Inside Bureaucracy (1967), is a foundational text in public administration and political economy. Downs combines economic rationality assumptions with political realism to explain how bureaucracies behave.

Theoretical Foundation

Downs approaches bureaucracy as a system composed of self-interested individualsoperating within structured incentives. He rejects romanticized views of public servants as purely altruistic, instead positing that:

- Bureaucrats aim to maximize personal utility, including income, power, prestige, and job security.

- Organizations tend to preserve and expand themselves, not just solve public problems.

- Bureaucratic behavior can be explained through economic logic, modified by institutional constraints.

From this foundation, Downs articulates a life-cycle model of bureaucratic behavior: how agencies emerge, grow, ossify, and ultimately resist change.

Stages of the Bureaucratic Rigidity Cycle

Creation and Innovation

- Agencies are typically created in response to perceived crises or public demand for new services.

- Early bureaucracies are lean, flexible, and mission-driven. They attract idealists, policy entrepreneurs, and technical experts.

- Decision-making is often centralized, informal, and adaptive. Risk-taking is tolerated because the agency is under public and political scrutiny.

🧠 Analogy: A startup phase—high creativity, fluid hierarchy, experimental methods.

Expansion and Formalization

- As the agency proves its usefulness or builds political support, it grows in size, scope, and complexity.

- More formal procedures are introduced to ensure consistency, accountability, and legality. Standardization becomes a defense against political or legal backlash.

- Specialized subunits emerge. Jurisdictional boundaries harden.

- Political goals shift from mission accomplishment to budget maximization and turf protection.

🧠 Bureaucratic “middle age”: growing complexity, expanding staff, increased internal differentiation.

Stabilization and Institutionalization

- The agency matures. Most staff are career bureaucrats with narrow, procedural roles.

- Risk-aversion increases: taking bold action can jeopardize one’s career, while inaction rarely leads to punishment.

- The agency becomes internally focused—process over outcomes, compliance over experimentation.

- Innovation slows or ceases, unless prompted by strong external shocks or charismatic leadership.

🧠 Key feature: Procedural inertia—rules replace judgment; responsiveness declines.

Rigidity and Decline

- The organization becomes primarily concerned with self-preservation.

- Reform proposals are resisted, even if they improve efficiency or mission alignment.

- Bureaucratic goals may become divorced from public interest, sustained only by political alliances, regulatory capture, or inertia.

- The agency may persist long after its original purpose has been fulfilled or made obsolete by technological or economic change.

🧠 Pathological end-state: ossification, stagnation, resistance to change—what Downs calls the “conservation of bureaucracy”.

Institutional Pathologies Identified by Downs

Downs identifies several recurring patterns that reinforce rigidity:

- Goal Displacement: Original mission supplanted by internal objectives (e.g., budget size, number of staff).

- Information Asymmetry: Agencies control the information that political overseers rely on, shielding themselves from scrutiny.

- Regulatory Capture: Close relationships with industry reduce willingness to innovate or enforce.

- Rule Proliferation: Accumulation of procedures, often created to avoid blame, leads to complexity and paralysis.

- Type II Bureaucrats: Individuals who seek quiet, secure careers and therefore avoid controversy or bold innovation.

These patterns make bureaucracies highly resistant to exogenous technological or societal change—a crucial insight for today’s challenges in electricity and climate policy.

Strategic Implications

Downs offers no panacea but implies that periodic reorganization, external competition, leadership change, or sunset provisions are necessary to counteract rigidity. In modern terms, this suggests:

- Innovation offices or “skunkworks” teams within bureaucracies,

- Independent oversight or performance auditing,

- Mechanisms for stakeholder co-governance to refresh legitimacy and responsiveness.

Application to Electricity Regulation and Innovation

This framework is strikingly applicable to public utility commissions (PUCs), ISO/RTOs, and incumbent utilities:

- PUCs were created in the early 20th century to manage monopolies and protect consumers—innovative at the time. But today, many exhibit rigid characteristics: legalistic dockets, defensive posture toward new actors, and outdated planning frameworks.

- Distribution utilities often treat innovation as a compliance burden. Rules are used to protect existing cost-recovery models and infrastructure spending pipelines.

- Distribution system planning, DER integration, EV-grid coordination all confront these structural rigidities. Even well-meaning bureaucrats are embedded in rule-bound systems that discourage experimentation and delay adaptation.

In short: Downs’ rigidity cycle explains why electricity institutions lag behind both public expectations and technological potential.

Final Thought

Anthony Downs’ work on bureaucratic rigidity offers an enduring and powerful critique: the very institutions we build to solve public problems can become obstacles to their solution over time. His theory remains essential for understanding why regulatory reform is difficult, why innovation stalls within entrenched systems, and how policy entrepreneurs must work not just within institutions but also on them.

Would you like this analysis in a visual lifecycle diagram as well? Or perhaps connected to Elinor Ostrom’s institutional change framework for a comparative angle? [My response: Yes, please analyze how Downs’ work compares to Ostrom’s institutional change framework.]

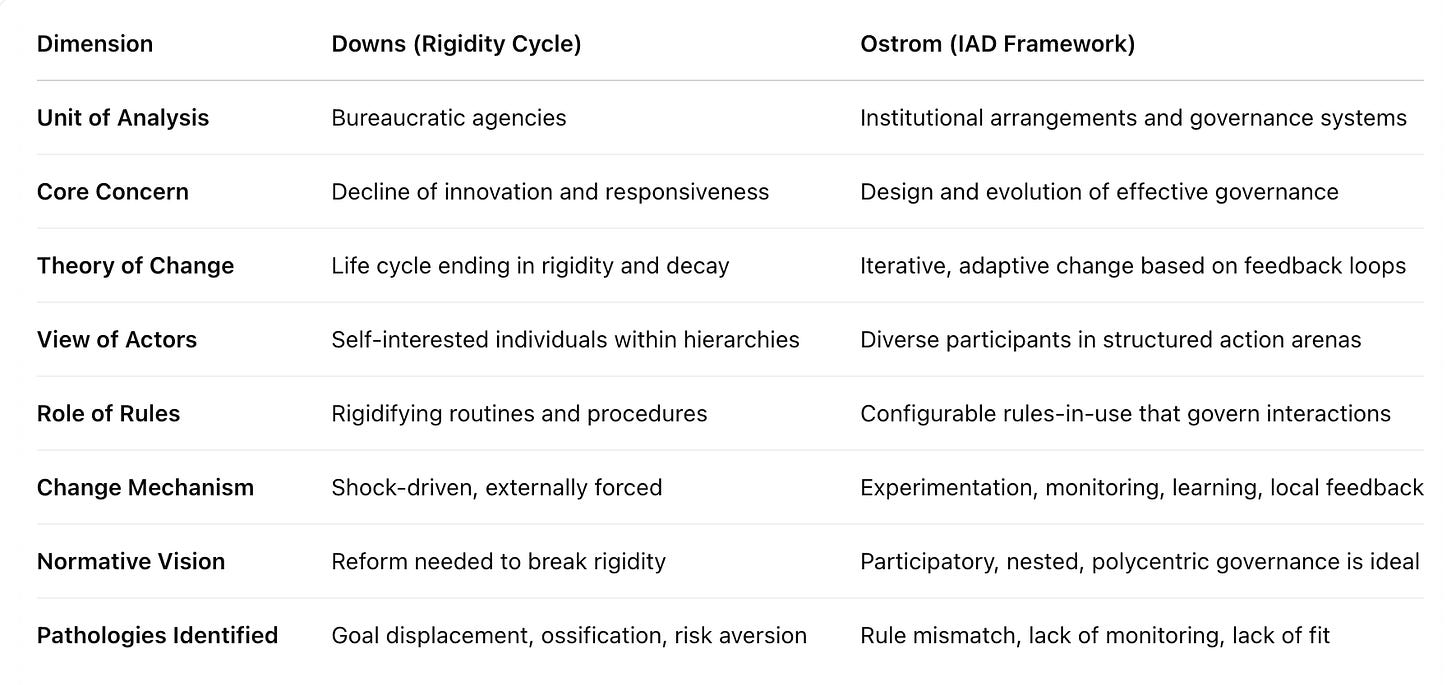

Excellent. Comparing Anthony Downs’ bureaucratic rigidity cycle to Elinor Ostrom’s institutional change framework reveals two fundamentally different but complementary perspectives on how institutions behave and evolve. Downs is focused on bureaucratic organizations and their pathologies, while Ostrom provides a systematic model of institutional design and adaptive governance—especially in polycentric, resource-constrained environments.

Let’s break down both frameworks, identify their points of convergence and divergence, and then reflect on their relevance to electricity regulation and innovation.

🧱 Anthony Downs: Bureaucratic Rigidity Cycle

Core Proposition:

Bureaucracies evolve through a predictable life cycle from creative, mission-driven entities to rigid, self-preserving organizations. The key force is internal organizational dynamics shaped by self-interested actors and structural inertia.

Key Characteristics:

- Focus on formal, hierarchical organizations—especially public agencies.

- Emphasizes incentives, routines, internal specialization, and risk aversion.

- Diagnoses decline through goal displacement, procedural inertia, and information asymmetry.

- Change is episodic, often requiring external shocks or political pressure.

🌐 Elinor Ostrom: Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) Framework

Core Proposition:

Institutions are rules-in-use that govern behavior, especially in collective action settings. They are embedded in nested, multi-level systems, and can be analyzed, designed, and adapted through participatory, iterative processes.

Key Characteristics:

- Focuses on governance systems, not just formal bureaucracies.

- Emphasizes polycentricity, local knowledge, rules-in-use, and co-production.

- Institutions are shaped by actors operating in an action situation, influenced by rules, norms, biophysical conditions, and community attributes.

- Change is gradual, experimental, and endogenous to the system.

🔍 Comparative Analysis

🧠 Theoretical Tensions and Complementarities

🔁 Complementarity:

- Downs explains why existing public bureaucracies often fail to respond to new problems—even when solutions are known.

- Ostrom offers a diagnostic and prescriptive framework for building institutions that can adapt, self-correct, and sustain trust.

Together, they form a diagnosis + design pair:

- Downs = Pathology: Why innovation stalls and institutions become brittle.

- Ostrom = Possibility: How adaptive institutions can be designed and reformed.

❗ Tension:

Downs is fundamentally more pessimistic about bureaucratic adaptability. He implies that unless major structural reform is imposed, bureaucracies will decay into inflexibility.

Ostrom, by contrast, is optimistic about self-governance and institutional resilience—provided there are the right incentives, monitoring, and participation mechanisms.

⚡ Application to Electricity Regulation

Downsian Lens:

- PUCs and IOUs are in late stages of rigidity: legalistic procedures, risk-averse decision-making, resistance to performance-based regulation or DER integration.

- Reform is blocked by internal inertia and external capture.

Ostromian Lens:

- A polycentric grid (e.g., municipal utilities, community energy projects, DER aggregators, local markets) can be more adaptive.

- Governance reforms should empower local actors, introduce rule flexibility, and establish clear monitoring mechanisms.

Combined Insight:

To modernize electricity regulation, we need to overcome the Downsian rigidity of legacy institutions by building Ostromian governance structures—polycentric, participatory, and capable of learning. Reform is not just about deregulation or central mandates; it’s about cultivating institutional diversity and capacity for experimentation.

📌 Final Reflection

Both Downs and Ostrom were deeply concerned with how institutions respond—or fail to respond—to changing environments.

- Downs shows us why institutional reform is difficult.

- Ostrom shows us how it can be done—through layered, participatory, adaptive rulemaking.

In electricity regulation, the challenge is to diagnose rigidity without falling into fatalism, and to design flexibility without losing coherence. Marrying their insights is essential for transforming static, centralized utilities into dynamic, responsive systems that can meet 21st-century energy challenges.

This piece was originally published on Lynne’s Substack, Knowledge Problem. If you enjoyed this piece, please consider subscribing here.