Few people are aware of the fact that “climate change” means very different things in science and in policy. That difference exposes the fundamental incoherence of climate policy, highlighted by the recent rediscovery that there is more to increasing global temperatures than just greenhouse gas emissions.

Remarkably, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change (UN-FCCC, 1992) use different definitions of “climate change.”

The IPCC defines climate change as:

A change in the state of the climate that can be identified (e.g., by using statistical tests) by changes in the mean and/or the variability of its properties and that persists for an extended period, typically decades or longer. Climate change may be due to natural internal processes or external forcings such as modulations of the solar cycles, volcanic eruptions and persistent anthropogenic changes in the composition of the atmosphere or in land use.

Under the IPCC, any change in the statistics of weather, regardless of cause, is thus climate change.

In contrast, the UN-FCCC adopted a much narrower and scientifically inaccurate definition of climate change:

[A] change of climate which is attributed directly or indirectly to human activity that alters the composition of the global atmosphere and which is in addition to natural climate variability observed over comparable time periods.

Thus, under the UN-FCCC, the only change in the statistics of weather that count as “climate change” are those that result from human activity that alters the composition of the atmosphere. By “human activity that alters the composition of the atmosphere,” the UN-FCCC explicitly means greenhouse gases, as you can see above from Article 2 of the UN-FCCC.

If the sun got just a bit brighter next year, leading to climate chaos and massive changes in global weather events for the next half-century, that would be climate change under the IPCC, but it would not under the UN-FCCC. If that sounds bizarre — it is!

Under the UN-FCCC’s limited definition of climate change, climate policy has evolved from a focus on direct measures of greenhouse gases — such as emissions and atmospheric concentrations — to a focus on global average surface temperature, formalized in the 2015 Paris Agreement under the UN-FCCC.

The Paris Agreement focuses on specific temperature targets, with a goal of:

Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above preindustrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change.

The shift from a focus on greenhouse gases to global average temperatures occurred based on the belief that the only factor responsible for changes in the statistics of global temperatures was greenhouse gases — so temperatures could serve as a proxy metric.

In 2017, Carbon Brief sought to explain why temperatures and greenhouse gas emissions were proxies:

Humans emissions and activities have caused around 100% of the warming observed since 1950, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) fifth assessment report. . . Since 1850, almost all the long-term warming can be explained by greenhouse gas emissions and other human activities.

The logic of the 2015 Paris Agreement was based on the assumption that greenhouse gas concentrations and global temperatures were simply interchangeable variables.

In response, climate advocacy has shifted in recent years to emphasizing global surface temperatures as a proxy not just for emissions, but also human flourishing. The argument is simple — lower temperatures are better, higher temperatures are worse.

For instance:

- Katheryn Hayhoe: “The science tells us that every additional tenth of a degree of warming matters. Every ton of carbon dioxide that we produce has consequences”;

- Zeke Hausfather: “The 1.5 degree Celsius goal is ideal, but 1.6, 1.7 and 1.8 are also worlds where humans can survive and, to an extent, thrive”;

- Rob Jackson: “[P]assing 1.5 C means social and economic ‘chaos’ . . . Every tenth of a degree matters, before and after 1.5 C”;

A few days ago, upon hearing from a climate policy expert that missing the 1.5C Paris Agreement was not the end of the world, Ezra Klein of the New York Times expressed befuddlement:

I can’t tell the difference here between: “Every degree matters” and “We have been scaring you all unscientifically for decades in order to get you to move faster. But now that we’re moving slower, don’t worry too much.”

New research further challenges the logic behind equating greenhouse gas emissions with global temperatures and global temperatures with human flourishing.

According to Peter Cox of the University of Exeter, most of the planet’s warming this century is not due to greenhouse gases, but reductions in air pollution, mainly sulfur dioxide:

“Two-thirds of the global warming since 2001 is [sulfur dioxide] reduction rather than [carbon dioxide] increases”

A paper just published — Samset et al. 2025 — arrives at similar conclusions:

[A] time-evolving 75% reduction in East Asian sulfate emissions partially unmasks greenhouse gas-driven warming and influences the spatial pattern of surface temperature change. We find a rapidly evolving global, annual mean warming of 0.07 ± 0.05 °C, sufficient to be a main driver of the uptick in global warming rate since 2010.

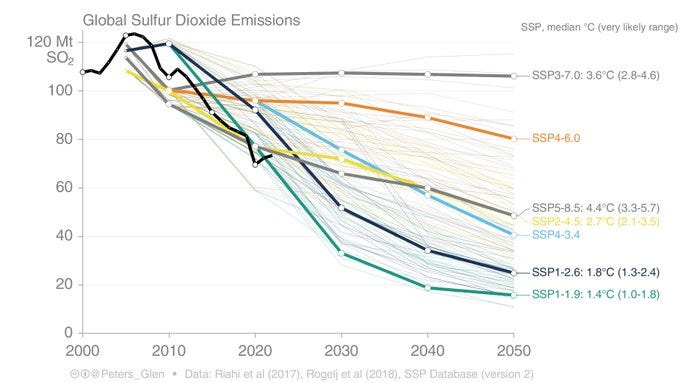

The figure above shows that sulfur dixide emissions have decreased over the past several decades at a rate much faster that most IPCC scenarios, and are expected to decrease further this century. Those future reductions will have the effect of increasing average global temperatures.

The fact that air pollution counteracts warming from greenhouse gases has long been understood, and has been discussed in depth in the scientific literature and the IPCC. However, the significance to climate policy of warming resulting from reducing air pollution appears not to have been well thought through.

For instance, Zeke Hausfather explains of planetary warming:

There is around half a degree of warming today that is “hidden” by aerosols. Without the cooling from sulphate and other aerosols, today’s global temperature would already be close to 2C above pre‑industrial levels, rather than the approximately 1.4C the world is currently experiencing.

That implies that the Paris Agreement’s temperature target of 1.5C has already been passed with respect to the warming contributions of greenhouse gases. Further success at reducing air pollution would push the world past the Agreement’s 2C target. For a champion of the UN-FCCC and its Paris Agreement, reducing pollution is thus an obstacle to achiving the treaty’s goals.

There are factors that contribute to changes in global average surface temperature beyond just greenhouse gases. That means that any climate policy focused on temperature targets will inevitably become incoherent — a point that my father has been making for decades — because the UN-FCCC focuses on greenhouse gases as the only climate policy control knob.

The fact that reducing air pollution would have an overall warming effect has long been discussed in the scientific literature. For instance, long-term projections of warming by the IPCC increased between the second (1995) and third (2001) IPCC assessments because of changing assumptions and modeling capabilities related to projected large future reductions in sulfur dioxide emissions. In 2005, Smith et al. argued that as recently as 1990, air pollution counterbalanced almost all increased radiative forcing due to accumulating greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

The policy incoherence runs much deeper.

Elsewhere, Hausfather argues that the temperature increases caused by reducing air pollution are on balance a “good thing”:

[W]e are rapidly reducing both aerosol emissions and their resulting climate cooling effect. Global emissions of SO2, the most important aerosol, have fallen by 40% since the mid‑2000s. China has cut its SO2 emissions more than 70% over the same period. This is a good thing; SO2 is a major precursor to PM2.5, which is responsible for millions of deaths from outdoor air pollution worldwide.

By this logic, apparently some warming is acceptable.

Instead of “every tenth of a degree increase in global temperatures matters” it is instead “every tenth of a degree matters unless the benefits associated with that increased tenth of a degree are larger than the costs of avoiding it.”

Less catchy, more accurate.

Reducing air pollution has costs as well, but also many benefits. But be careful acknowledging that fact in the context of climate policy, because it turns out that burning fossil fuels also has costs, but is similarly accompanied by many benefits.

The narrow definition of climate change of the UN-FCCC and its myopic policy focus on greenhouse gas emissions contributes to what Mike Hulme has called climate reductionism: “the ideology – the settled belief – that the dominant explanation of all social, economic and ecological phenomena is a human-caused change in the climate.”

The UN-FCCC takes the reductionism even further by restricting “human-caused changes in climate” to only those associated with greenhouse gas emissions. If the big greenhouse gas emissions knob is the only policy control you have, then that will inevitably become a singular focus.

Climate policy has been steered into a political cul-de-sac by bad science and bad policy. The bad science can be found in the UN-FCCC’s definition of climate change that is at odds with the scientifically-accurate definition of climate change of the IPCC. The bad policy results from the use of global average temperatures as a proxy for human flourishing, making cost-benefit analyses seem unnecessary or even unhelpful to the political cause.

[T]here are some futures beyond 1.5 degrees C (or even 2 degrees C) that are more desirable than other futures which do not exceed these warming thresholds.

It is long overdue for climate policy discussions to take that seriously.