Last week, SpaceX pushed back its timetable for the launch of Starship, the most powerful rocket ever built, and singled out government regulations as the cause:

Unfortunately, we continue to be stuck in a reality where it takes longer to do the government paperwork to license a rocket launch than it does to design and build the actual hardware. This should never happen and directly threatens America’s position as the leader in space.

While the company wasn’t explicit in the post, it is no secret that SpaceX has struggled with satisfying the Federal Aviation Administration’s standards under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) amid concerns over the environmental impact of the launches.

Last week in Techne, I discussed the notion of vetocracy, and one of the biggest pushbacks I got was that I wasn’t being specific enough. But I see vetocracy as a catchall for many of the problems created by veto power. Vetocracy is about slowing the throughput of government so it takes longer to finalize approvals for cellphone towers, radio antennas, buildings, housing, railways, the hardware of the internet, parks, permits for food service, energy projects, events, and pharmaceuticals.

NEPA is a big contributor to the vetocracy.

A short history of NEPA.

The National Environmental Policy Act was the first in a series of environmental laws signed by President Richard Nixon in the early 1970s, which also included the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (1970), the Clean Air Act (1970), the Clean Water Act (1972), and the Endangered Species Act (1973).

The original version of the law was fairly short at just five pages, and, as typical of the era’s environmentalism, stressed “the profound impact of man’s activity on the interrelations of all components of the natural environment,” with a particular emphasis on “the profound influences of population growth, high-density urbanization, industrial expansion, resource exploitation, and new and expanding technological advances.”

When enacted, the big thing NEPA did was create the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) within the White House. But in hindsight, it’s clear the most important part of NEPA was Section 102(2)(C), which directs all agencies of the federal government to

Include in every recommendation or report on proposals for legislation and other major Federal actions significantly affecting the quality of the human environment, a detailed statement by the responsible official on the environmental impact of the proposed action, any adverse environmental effects which cannot be avoided should the proposal be implemented, alternatives to the proposed action, the relationship between local short-term uses of man’s environment and the maintenance and enhancement of long-term productivity, and any irreversible and irretrievable commitments of resources which would be involved in the proposed action should it be implemented.

It took no time at all for this part of the law to end up in the courts. Following NEPA’s passage, the United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) updated its licensing regulations to align with the new legal framework. However, these revisions faced a legal challenge from the Calvert Cliffs’ Coordinating Committee, a group of attorneys who argued the AEC’s rules fell short of NEPA’s mandate for comprehensive environmental impact assessments for the Calvert Cliffs Nuclear Power Plant, then under construction in Maryland.

In 1971 Judge J. Skelly Wright of the D.C. Circuit Court ruled in favor of Calvert Cliffs’ Coordinating Committee, writing that,

These cases are only the beginning of what promises to become a flood of new litigation — litigation seeking judicial assistance in protecting our natural environment. Several recently enacted statutes attest to the commitment of the Government to control, at long last, the destructive engine of material “progress.”

As part of the decision, the judge laid out a series of procedures and established the precedent for agencies to follow in order to comply with NEPA. As a result, the Atomic Energy Commission suspended all nuclear power plant licensing for 18 months. The Calvert Cliffs Nuclear Power Plant eventually secured regulatory approval and remains in service today.

Still, what’s deeply ironic about this case is that the judge explicitly stated that the court’s duty “is to see that important legislative purposes, heralded in the halls of Congress, are not lost or misdirected in the vast hallways of the federal bureaucracy.” But it was this decision that helped to create a new type of vetocratic bureaucracy. The focus on procedure over substance has become a hallmark of NEPA and one of its biggest flaws.

As my former colleague and economist Eli Dourado pointed out in his aptly titled 2022 piece, “Much more than you ever wanted to know about NEPA,” the ruling, in conjunction with the text of NEPA, tipped the scales of power away from agencies tasked with drafting Environmental Impact Statements (EIS). An EIS is a crucial document that outlines the environmental consequences of a proposed project. As Dourado wrote,

Normally in administrative law, agencies are entitled to tremendous discretion. The standard of review typically applied when there is no question of statutory interpretation is whether the decision is “arbitrary, capricious, or an abuse of discretion,” an extremely deferential standard. You can’t usually haul a federal official into court and expect to win because you don’t agree with a finding or an action.

But NEPA lawsuits change the balance of power. Because NEPA made the EIS a required part of administrative procedure, the arbitrary and capricious standard applies to the EIS itself, not just the federal action. A judge might find no fault at all in the agency’s ultimate decision, but find that some element of the EIS is arbitrary. If you can persuade the court that an EIS is deficient in any way, the agency decision will usually be vacated and the agency ordered to fix the problem with the EIS.

The basics of the NEPA process.

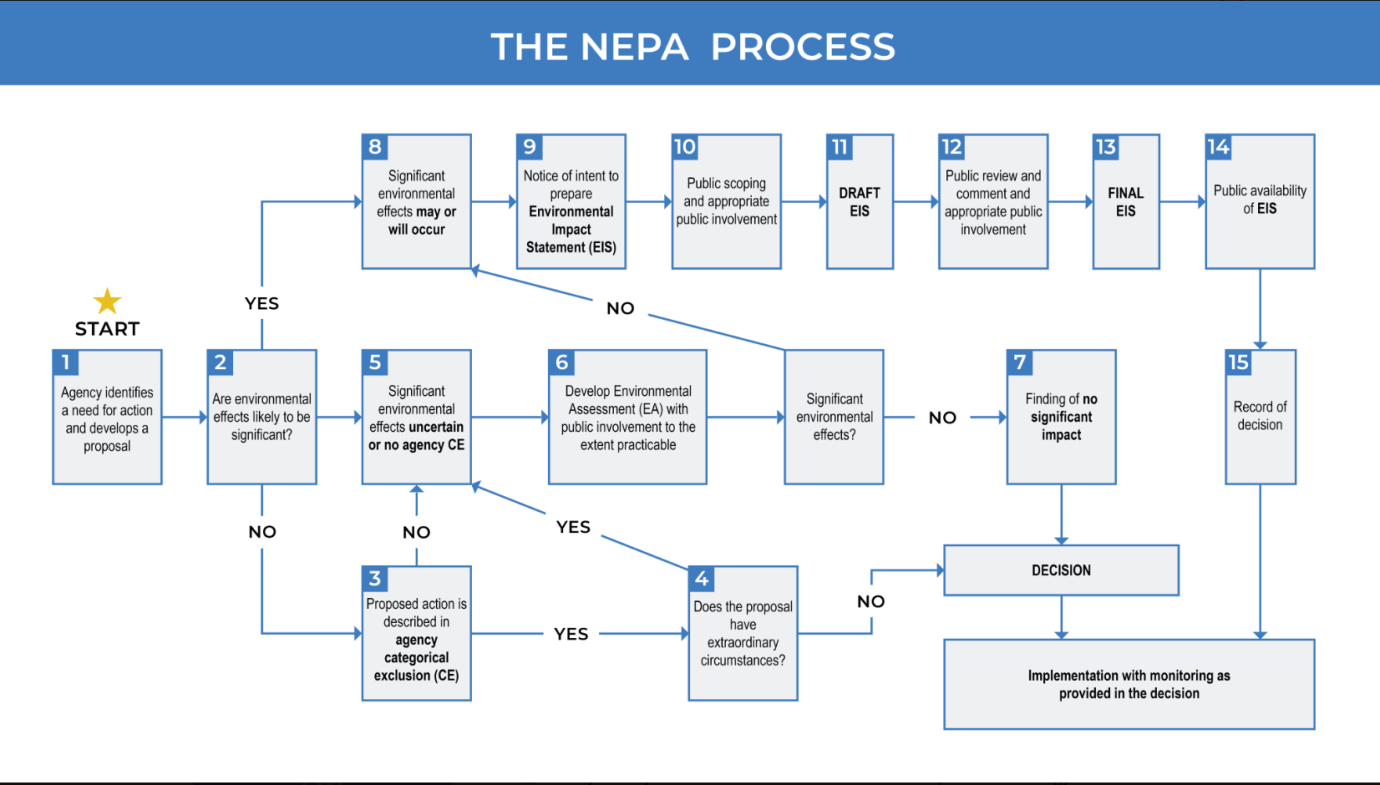

Nearly 50 years of court rulings on NEPA has resulted in a three-part system of review.

Most projects an agency will want to undertake will be subject to a categorical exclusion (CE), which is a fairly broad class of actions that do not have a significant effect on the human environment. These agency actions include paying federal employees, closing a road because of fire danger, restructuring debt, and a bunch of others, depending on the agency. While there is no comprehensive dataset tracking all federal NEPA actions, a 2014 report by the Government Accountability Office estimated that roughly 95 percent of NEPA analyses are categorized as CEs. Not surprisingly, each agency has its own process for determining a CE, as well as the rest of the NEPA process.

If the proposed action doesn’t fall into a CE, the federal agency will prepare an Environmental Assessment (EA). This determines whether or not a federal action has the potential to cause significant environmental effects. Federal actions include adopting agency rules or regulations, approving federal programs or plans, endorsing specific projects, issuing federal permits or regulatory decisions, and undertaking activities that are federally funded or supported. Based on the EA, the agency could determine that the action will not have significant environmental impacts, resulting in the issuance of a Finding of No Significant Impact. Such a finding explains why the agency has concluded that there are no significant environmental impacts. However, if the EA determines that the environmental impacts will be significant, then an Environmental Impact Statement is prepared.

Going through an EIS is a detailed process:

- It begins with an agency publishing a Notice of Intent in the Federal Register, alerting the public to the forthcoming environmental analysis and outlining ways for public involvement.

- A draft EIS is then made available for public review and comment for at least 45 days.

- After the comment period closes, agencies review all substantive feedback, potentially conducting further analysis.

- Once finalized, the EIS is published, addressing these comments.

- Then, a mandatory 30-day waiting period follows.

- Next, the EPA issues a Notice of Availability in the Federal Register for both draft and final EISs.

- The process concludes with a Record of Decision, which details the agency’s final decision, alternatives considered, and plans for mitigation and monitoring.

All of this takes time. Every year, the National Association of Environmental Professionals issues a report on EISs and the most recent estimate from 2022 found that a typical federal agency took more than four years on average to complete an EIS. What’s more, in 2020 the Trump administration issued a report that suggested the median EIS ran to a length of 661 pages. This is a dramatic increase from the earliest EISs, which were less than 10 typewritten pages. Years of litigation have caused them to balloon in size.

NEPA is not only a powerful law but an influential one. Twenty states now have their own versions. While these state iterations share the same core objective of ensuring thorough environmental review, they often come with additional procedural requirements and vary in terms of scope and application. The result is a complex, layered regulatory landscape where federal, state, and local agencies must navigate overlapping obligations.

The cost of NEPA.

In the right (wrong?) hands, the complex system of approvals created by NEPA and its state variants can stall all kinds of projects.

As reported by the Marin Independent Journal, property owners in Marin County, California, have tried unsuccessfully to block George Lucas, the filmmaker who is a longtime area resident, from developing a vineyard. The residents allege the project may violate the California Environmental Quality Act and claim the vineyard is an aesthetic “eyesore” compared to the expansive pastureland that previously existed.

There are many examples like this.

Two years ago, Berkeley residents weaponized the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) to stop the University of California, Berkeley from building a new dorm, arguing that the project polluted the neighborhood. It took an act of the California Legislature to finally get the dorms built. The National Park Service wanted to replant California’s burned sequoia groves but environmentalists sued to stop it. The old Lane Medical Library in San Francisco was set to be redeveloped into housing, winning unanimous support at the city’s Historic Preservation Commission and Planning Commission, but it is currently on hold because of a CEQA lawsuit filed by a neighbor.

A sluggish permitting process delays when a project can start earning revenue. Since every project must make back its investment over a 10- to 20-year period, these delays compress the time a project has to make returns. Altogether, this makes the project less attractive financially.

Offshore wind projects have been canceled because of NEPA. Broadband infrastructure has been slowed by NEPA. And sadly, a wildfire destroyed half a forest in Montana before the U.S. Forest Service could complete a wildfire prevention plan that necessitated an environmental impact statement. The examples go on and on.

Reforms and what’s next.

The House Committee on Natural Resources is currently weighing a draft bill that would alter NEPA to make the process smoother, cheaper, and less likely to lead to lawsuits. I happen to be a fan of it, but I can understand why it is still in its draft form. There’s lots of disagreement from Democrats on how—and even whether—to reform NEPA. The committee’s chairman, Arkansas Rep. Bruce Westerman, wants to work out those differences before officially filing.

One of the major revisions proposed would redefine NEPA as a procedural statute, making it clear that while agencies must consider environmental impacts, they are not required to produce specific outcomes. Additionally, the draft bill seeks to limit the scope of environmental reviews to impacts under an agency’s direct control. This would expedite reviews by reducing the number of alternatives agencies are required to consider.

The bill also would introduce a 120-day statute of limitations for lawsuits challenging NEPA decisions and limit the right to sue to individuals or groups that have participated in the public comment process, aimed at reducing frivolous litigation. Moreover, it would allow more low-impact projects to qualify for categorical exclusions, bypassing detailed environmental reviews.

But the biggest change would be the alteration in judicial processes. Under the bill, courts would be limited in granting injunctive relief and remand. They could grant relief only if moving forward with the proposed action would cause “proximate and substantial environmental harm.” I have a feeling this would do a lot to curtail frivolous lawsuits that use NEPA to stop projects. But I’m not sure it would really alleviate the burden that environmental impact statements place on all large projects.

But we should go further, as my former colleagues have suggested, by establishing emergency and national interest exclusions, and expanding categorical exclusions, at a minimum.

Creating something beneficial and preventing its creation should not be morally equivalent actions, but they are under the law. I hope that changes.

Learn more: A Risk-Based Theory of Regulation and Regulatory Capture | How the Vetocracy Paralyzes Progress | California’s SB 1047 Moves Closer to Changing the AI Landscape | Your Autonomous Vehicle Ride Might Take a While