A few days ago Australian legislators introduced a bill focused on “Combatting Misinformation and Disinformation.” The Australian Parliament explains the purpose of the bill:

The bill proposes to amend the Broadcasting Services Act 1992 and would make consequential amendments to other Acts to establish a new framework to safeguard against serious harms caused by misinformation or disinformation.

The bill would provide the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) with new regulatory powers to require digital communications platform providers to take steps to manage the risk that misinformation and disinformation on digital communications platforms poses in Australia.

The proposed legislation defines misinformation and disinformation as follows:

Misinformation is false information that is spread due to ignorance, or by error or mistake, without the intent to deceive.

Disinformation is knowingly false information designed to deliberately mislead and influence public opinion or obscure the truth for malicious or deceptive purposes.

The legislation is silent on how “false information” is defined and by whom. In the Explanatory Memorandum that accompanies the bill a media organization — the self-appointed Australian Associated Press (AAP) FactCheck — is cited as an example of an arbiter of truth claims, and thus with implied governmental authority to identify true and false claims under the proposed legislation.

Illustrating why this approach is misguided, the Australian Human Rights Commission critiqued an earlier version of the bill:

Drawing a clear line between truth and falsehood is not always simple, and there may be legitimate differences in opinion as to how content should be characterised. The broad definitions used here risk enabling unpopular or controversial opinions or beliefs to be subjectively labelled as misinformation or disinformation, and censored as a result. . .

. . . the draft bill defines any content that is authorised by the government as being excluded content. This means government information cannot, by definition, be misinformation or disinformation under the law.

This fails to acknowledge the reality that misinformation and disinformation can come from government. Indeed, government misinformation and disinformation raises particular concerns given the enhanced legitimacy and authority that many people attach to information received from official government sources.

This specific exclusion privileges government content but fails to accord the same status to content authorised by the opposition, minor parties or independents.

The result is that government content can never be misinformation but content critical of the government produced by political opponents might be.

The concern that government officials might weaponize “misinformation” laws in support of their agendas and in opposition to their perceived opponents is not just speculative — Grab a coffee, let me tell you a story.

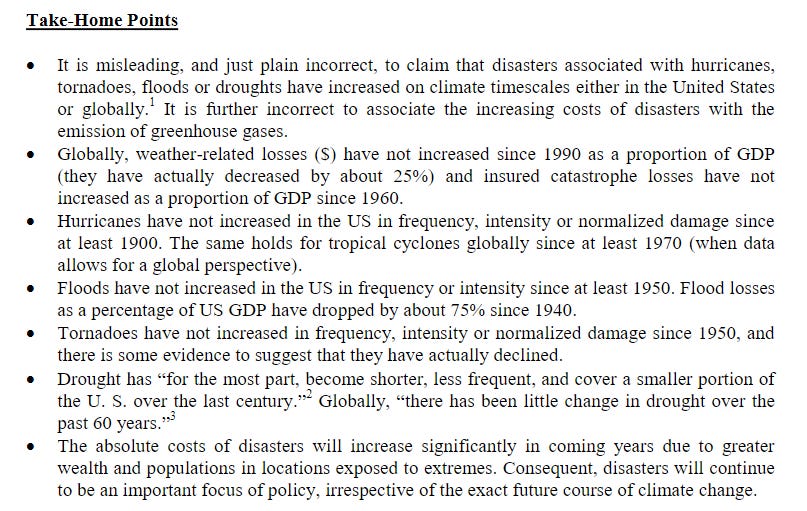

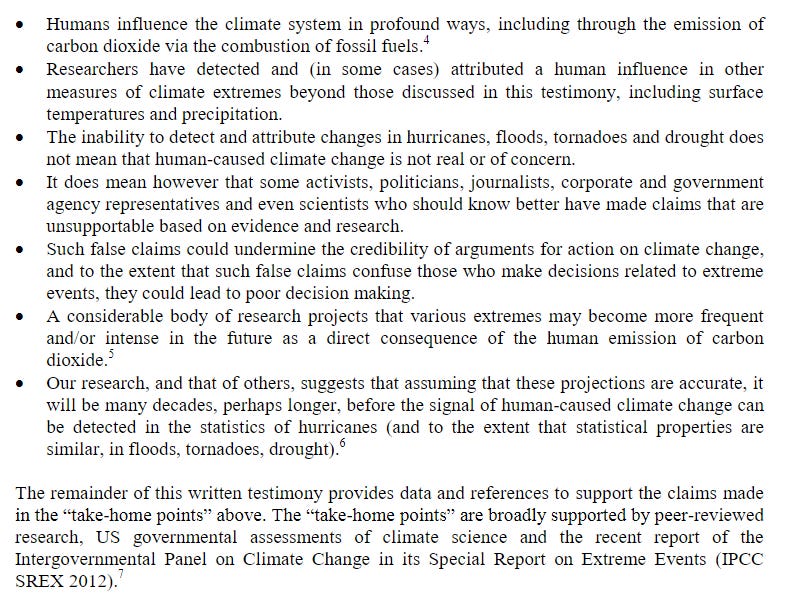

Back in July 2013, I testified before the U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works on the findings of the then-recent IPCC Special Report on Extreme Events (SREX). Here were my top line conclusions, which will no doubt be familiar to THB readers:1

I also included some statements of my broader views of climate change and policy:

For whatever reason, my testimony went viral — quickly racking up more than 400,000 views on YouTube.

Early the next year, in February 2014, President Obama’s science advisor Dr. John Holdren, who was also the director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), testified before the same committee. In a press conference held a few weeks earlier, Holdren had made strong claims — much stronger than the conclusions of the IPCC or U.S. National Climate Assessment — of detection of changes in drought and attribution of those changes to greenhouse gas emissions:

. . . global climate change is increasing the intensity and the frequency and the length of droughts in drought-prone regions. This is one of the better understood dimensions of the relationship between global climate change and extreme weather in particular regions.

At the hearing, Senator Jeff Sessions (R-Al) asked Dr. Holdren about these comments, invoking my previous testimony. Holdren responded by claiming (contrary to the IPCC and evidence) that drought was in fact increasing globally but was masked by increasing precipitation in other places, so that when those data are combined the globally increasing drought disappeared. He then claimed (again falsely) that I was not part of the scientific “mainstream” (despite being widely cited, including by the IPCC):

Mr. Holdren. So when you say global drought, if I may finish, when you say global drought, you are averaging out the places that are getting drier and the places that are getting wetter. What I am talking about is what has been happening in drought-prone regions. The first few people you quoted are not representative of the mainstream scientific opinion on this point.

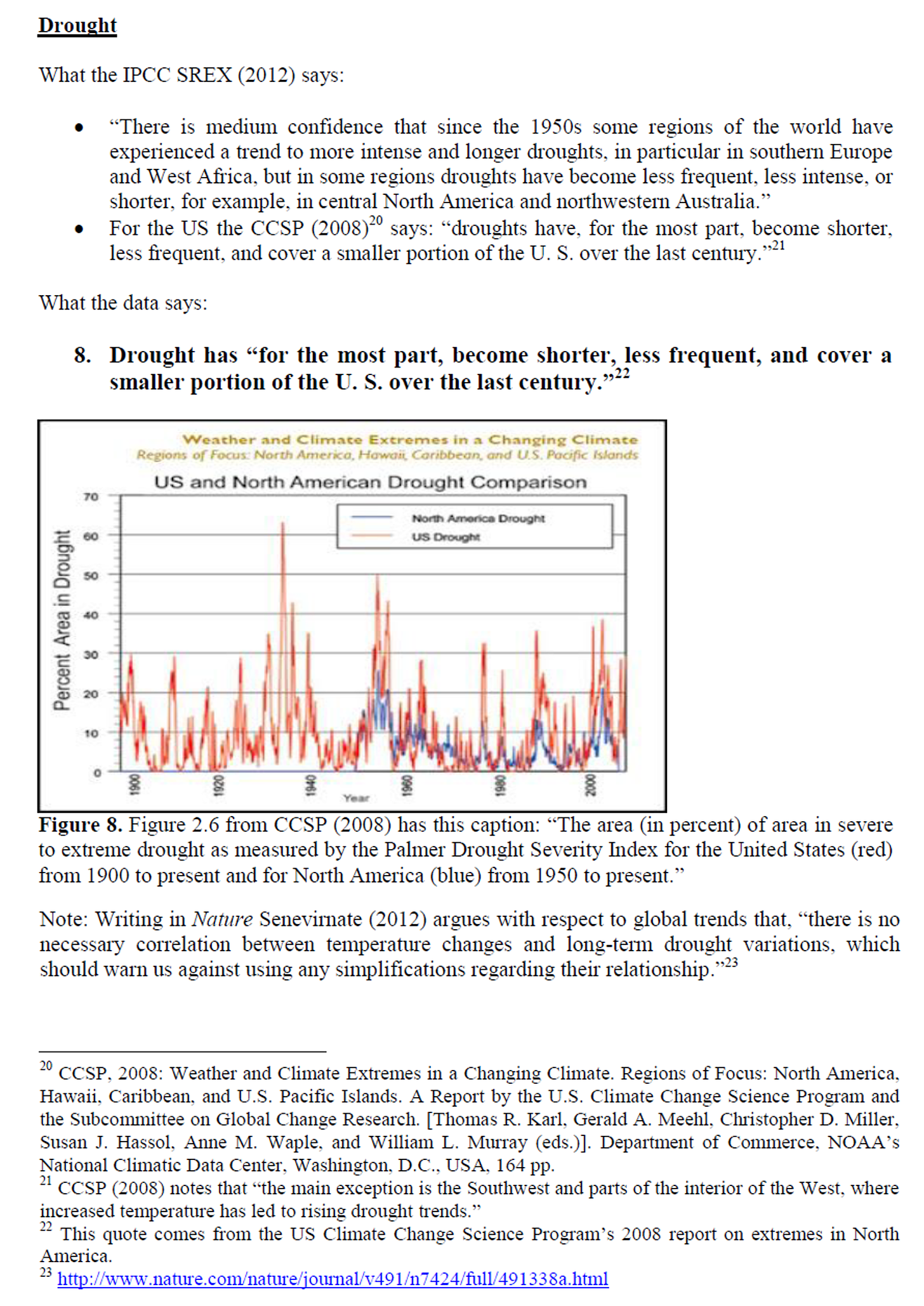

My earlier testimony to which Holdren was responding included just one page on drought, and it was almost entirely quotes from the IPCC and US NCA. Here is that one page — neither the IPCC nor the US NCA presented strong claims of attribution:

As their exchange concluded, Senator Sessions had a last little dig at Dr. Holdren:

Senator Sessions: We expect that a taxpayer paid government official should be very accurate and not advance a political agenda but tell us the absolute facts.

Holdren returned to the White House and was apparently not particularly happy with how he had come across. A few days later the White House published on the White House website a six-page, single-spaced statement under Holdren’s byline, titled, “Drought and Global Climate Change: An Analysis of Statements by Roger Pielke Jr.”2

Holdren and the Obama White House had thus turned a discussion about what the IPCC and US NCA say about drought into an attack on me. In Dr. Holdren’s screed, the word “Pielke” appears nine times, “IPCC” eight times. He called me “not representative of mainstream views” and “seriously misleading.”

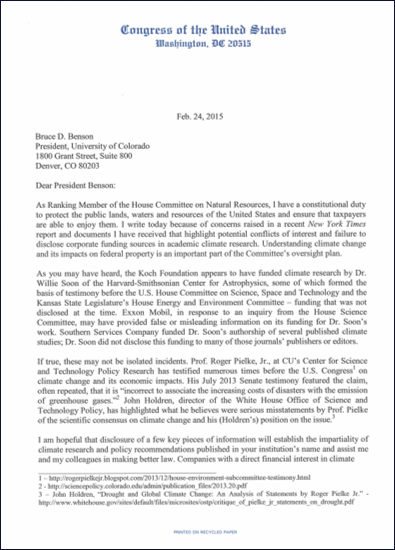

I am — to my knowledge — the only academic or researcher singled out by the White House for such an attack, proving to me that the “Bully pulpit” is very real. The White House missive led to an avalanche of online mobbing. More significantly, less than a year later the White House memo led to a Congressional investigation, based on the claims that I had contradicted the views of Dr. Holdren.

The letter announcing my investigation (below) explained:

John Holdren, director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, has highlighted what he believes were serious misstatements by Prof. Pielke of the scientific consensus on climate change and his (Holdren’s) position on the issue.

While these events occurred a decade ago, I can still feel the chill of being told that the White House and U.S. Congress were coming after me professionally, justified by a (false) claim that my views were not aligned with some invoked “scientific consensus” or contrary to an Obama administration political appointee who had far less expertise in the subject than I did.

But even if my views were contrary to some alleged scientific consensus — that would not be misinformation, misleading, or misstatements. There is of course no problem with organizing scientific assessment bodies to take a snapshot of current understandings, contestations, uncertainties, and areas of ignorance. It fact such assessments are absolutely necessary.

Any such “consensus” that emerges from an assessment process is not a holy text whose exegesis can thereafter serve as an arbiter of truth. In fact, the only way that science advances is by challenging claims and subjecting them to scrutiny — even those claims that are widely accepted. Scientific knowledge is incredibly robust because of such challenges.

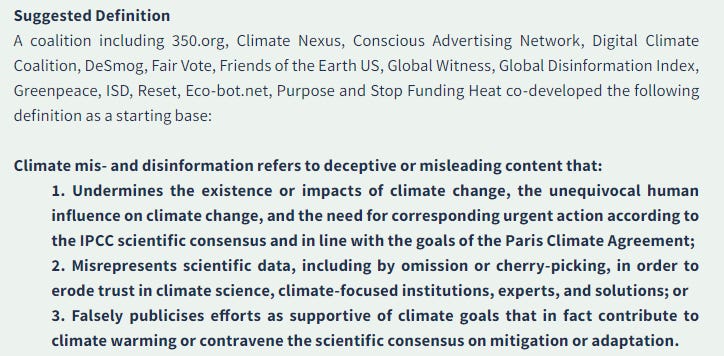

Back to Australia — Some argue that the proposed misinformation legislation does not go nearly far enough, singling out challenges to climate policy as expressions of “climate denial” that should be regulated by government officials to aid in the implementation of certain political agendas.

Both my inclination and experiences tell me that putting government officials in charge of regulating expression on contested political issues, overseen by “fact checkers,” is a bad idea. Imagine if I could have been fined or otherwise punished by the White House or Congress for expressing my expert, professional views in a public or policy setting? Their abuse of the “Bully pulpit” was bad enough — creating a legal basis for such abuses would compromise science and democracy.

I am no expert on the implied right to free speech in Australia, but I can attest that science and politics both benefit from the open and free exchange of ideas, even those that you or I (or anyone else) may disagree with.

More broadly, propaganda offers a much better framing characterizing political speech than does misinformation. The only effective and democratically legitimate way to counter propaganda is with better propaganda. Its a subject I’ll engage more with in coming posts.

This post was originally published on Roger’s Substack, The Honest Broker. If you enjoyed this piece, please consider subscribing here.

Postscript. Sometime in the summer of 2015, after the Congressional investigation was well underway and I had already suffered a lot of professional consequences, early one morning as I was having my coffee, my phone rang. I picked it up, said hello, and heard, “Hold for Senator Sessions.” Senator Jeff Sessions came on the line and apologized for all the trouble his questioning of Holdren had caused for me. My own politics are pretty far from Senator Sessions, but I deeply appreciated the basic humanity of his call, reflecting that what we had in common was far more important than any policy or political differences.

1 You will notice that for drought, I quote directly from the relevant assessments, in contrast to my statements on hurricanes, floods, tornadoes, and global disasters. That is because I have not done primary research on drought but I have in these other areas.

2 The document’s metadata suggest that the comments were in fact authored by an intern.