Dave Jones, California’s insurance commissioner from 2011 to 2018, explained California’s growing insurance crisis in 2023:

Due to the failure to substantially reduce greenhouse-gas emissions in the U.S. and globally, we are marching steadily to an uninsurable future.

Jones sentiment is widely shared — Climate change is causing more and more intense extreme events, which are leading to more frequent and costly disasters, and as a result of growing economic losses, insurance companies are refusing to provide insurance coverage to homeowners. If the U.S. and the world would just reduce emissions, then risks of loss would decrease and the insurance crisis would be averted. Simple.

Also very wrong.

A long-term change in the frequency or intensity of extreme weather events would indeed alter the risk of loss. But insurance is about the management of risk. Without risk, insurance could not exist. As Cuthbert Heath, an early innovator in catastrophe insurance, explained more than a century ago: “Any risk is insurable at the right price.”

Changing risk does not lead to uninsurability. However, changing risk while restricting the ability to price appropriately in response, could lead to uninsurability. It is pricing, not risk, that underlies California’s insurance crisis. Let’s take a closer look.

Back in 1998, soon after Chris Landsea and I published our first paper estimating what damage past hurricanes would do under contemporary levels of population and wealth, we were contacted by someone in Florida’s government involved with insurance regulation. We were asked if we could apply our normalization just to hurricanes that affected Florida. We performed the requested analysis and shared our findings with Florida officials — Normalized hurricane losses for Florida under our methods implied much greater risk of loss than other contemporary methods of loss estimation, and thus implied a need for higher insurance rates for Florida homeowners. We did not hear back.

State regulation of insurance companies is generally viewed to be necessary to meet two goals: fair pricing for consumers and ensuring that insurance companies have adequate reserves for the largest of disasters.1 Of course, the determination of “fair pricing” and “adequate reserves” is subject to debate, and ultimately determined politically, and, ideally, informed by science.

In California, in 1988 a ballot initiative — Proposition 103, championed by Ralph Nader, called “Insurance Rate Reduction and Reform Act”2 — narrowly passed and subsequently transformed how California determined both “fair pricing” and “adequate reserves.” The law has led directly to California’s insurance crisis of 2025 because it prevents insurance companies from charging actuarially sound rates for homeowners insurance.3

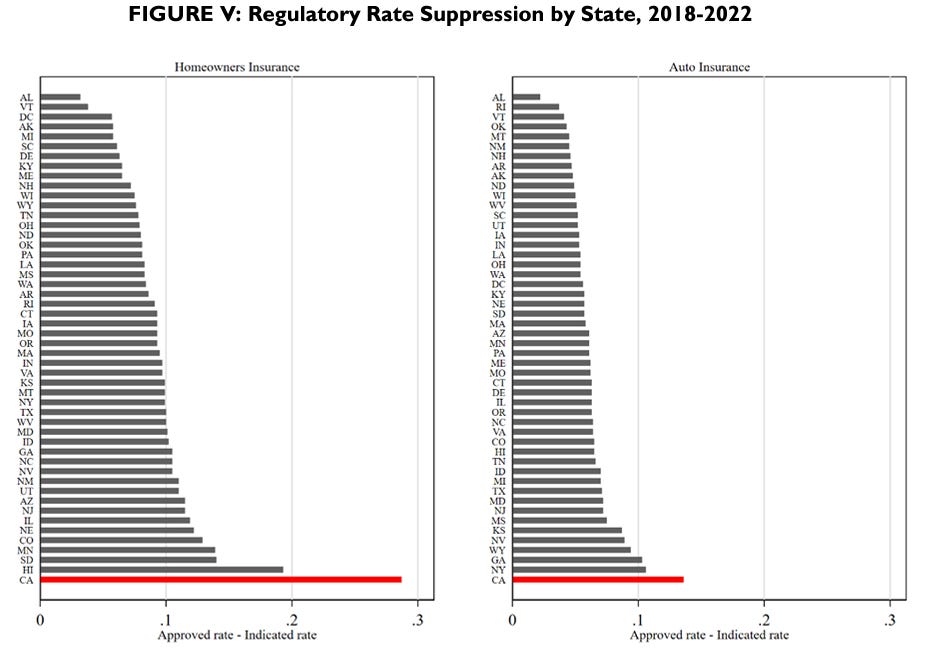

Rate suppression refers a situation when the actuarially appropriate insurance rate is larger than the actual rate approved by state regulators, which creates a situation where pricing of insurance does not accurately approximate risk. The figure below, from an analysis by the International Law and Economics Center (ILEC), shows that from 2018-2022 California had the largest rate suppression of any US state, and by a large margin.

The rates that insurance companies are allowed to charge in California are thus not high enough to enable insurance companies to cover the risks that they are taking. That gap is why companies like State Farm have reduced their exposure to the California market.

Why do California’s regulated insurance rates differ so markedly from those that are deemed to be more actuarially sound?

The answer is not climate change, but public policy — and specifically Proposition 103. Let’s look at three of its provisions that serve to suppress insurance rates.

First, the law requires that insurance companies calculate how they price insurance for fire catastrophes based only on loss experience of the past 20 years (or more):

In those insurance lines and coverages where catastrophes occur, the catastrophic losses of any one accident year in the recorded period are replaced by a loading based on a multi-year, long-term average of catastrophe claims. The number of years over which the average shall be calculated shall be at least 20 years for homeowners multiple peril fire . . .

A backward-looking approach to estimating future risk of loss is deeply problematic for several reasons.

One is change in risk — fire risk varies and changes over time and there is no guarantee that the experiences of the past twenty years would accurately characterize current or future risk. In fact, even in the absence of changes in climate, twenty years is far to short to accurately characterize climate and ecological variability.4 Climate change and variability mean that fire risk is not a simple constant.

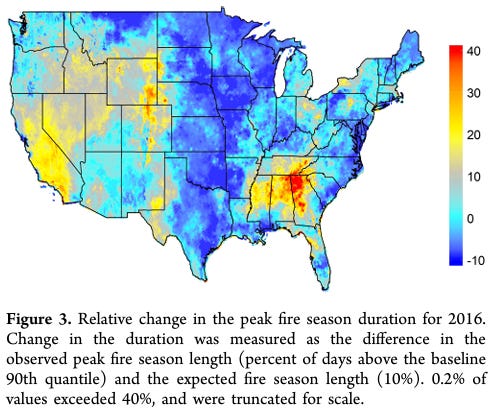

The figure below shows one measure of how fire risk changed from 1979 to 2016 in the continental United States — decreasing in many places, and increasing in others, including Southern California..

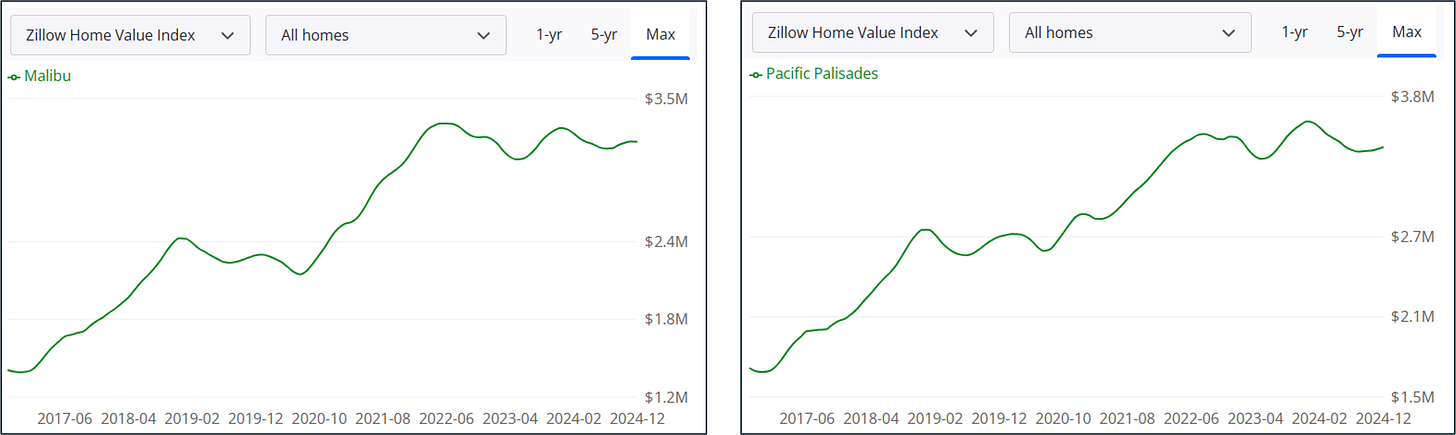

Another source of change relevant to estimating the risk of loss is in exposure and vulnerability. For instance, the graphs below, via Zillow, shows that house prices in Malibu and Pacific Palisades, two communities devastated by the recent fires, doubled over just 5 years. That rate of growth in valuation equates to 16x over 20 years. Even in locations with smaller levels of appreciation, using catastrophe losses from the past 20 years is bound to mislead.

Increasing property valuations over time mean that backwards-looking loss estimates will always underestimate contemporary and future estimates of risk of loss.

Yet another factor relevant to contemporary risk of loss is that more houses are being built in California (but apparently, not enough). According to one analysis— Berg et al. 2024 — over the period 2000 to 2020, housing in the wildland-urban interface in California increased by ~600,000 to ~800,000 units (depending on method) or roughly 20% of total housing stock in areas subject to wildfire. Development also means that backwards-looking loss estimates will always underestimate contemporary and future estimates of risk of loss.

A second, and related, provision of Proposition 103 that leads to suppressed insurance rates is that it does not allow the use of the best tools available to estimate current risks — catastrophe models that integrate considerations of risk, exposure, and vulnerability based on the more recently available data.

As the ILEC notes:

Insurers have access to tools like advanced wildfire catastrophe models that would allow them to project future wildfire losses in ways that consider both changing climactic factors and a given property’s proximity to fuel load. Such considerations are not currently permitted under California’s Prop 103 system, but nor are they explicitly barred, as such models largely did not yet exist in 1988.

Catastrophe models, which are allowed in California to estimate earthquake risks, are no panacea. Dag Lohmann, CEO of KatRisk, LLC, noted that wildfire catastrophe models can generate risk estimates that differ from each other by 300%. Even though cat models, as they are called, are not truth machines, they surely would tell us that wildfire risk in California is mispriced (and there can be little doubt that the companies limiting their exposure to the California market already know this).

As Jessica Weinkle and I argued in the context of hurricane catastrophe modeling in Florida, such models can also help to surface important questions about insurance that go beyond just pricing:

Models therefore come to include political positions on relevant knowledge and the risk that society ought to manage. Earnest consideration of model capabilities and inherent uncertainties may help evolve public debate from one focused on “true” or “real” measures of risk, of which there are many, toward one of improved understanding and management of insurance regimes.

The inability to consider catastrophe model estimates of wildfire risk in California established in law illustrates how inconvenient science is unwelcomed by policy makers across the political spectrum — in this case by California’s Democrats.

In addition, Proposition 103 allows does not allow consideration of reinsurance pricing in regulating state insurance rates. Reinsurance companies — who provide insurance for insurance companies — are sophisticated managers of risk. They make extensive use of catastrophe models and other tools. Pricing of risk in the global reinsurance market provides further valuable information that could be used to more appropriately price California wildfire risks.

The willful blindness of California’s policy makers to contemporary tools and evidence relevant to risk pricing led the ILEC to conclude that California “is effectively telling insurers to ignore the science.”

A third feature of Proposition 103 that works against better aligning pricing with risk of loss is that it changed the position of California insurance commissioner from being appointed to being elected. When state regulation of insurance results in higher prices for insurance that means greater economic costs to consumers, who also happen to be voters. No one wants more expenses.

What politician wants to run on a platform of or take responsibility for increasing (dramatically) the costs of historically underpriced insurance?

Pandering to voters also helps to explain why climate change is so often invoked as the cause of California’s insurance crisis. No politician wants to acknowledge that poor policies on their watch are in fact the real reason why insurers are fleeing the state, insurance availability is limited, and costs are rising.

For instance, Governor Gavin Newsom issued an executive order in September 2023that celebrated Proposition 103, suggesting the policy was well designed to keep consumer costs for insurance low:

WHEREAS in 1988, California voters enacted Proposition 103, which established a robust set of consumer protections designed to keep insurance rates fair and affordable and to ensure a competitive marketplace.

The culprit behind the crisis? You guessed it:

WHEREAS climate change has made California hotter and drier over the last several decades, resulting in more frequent wildfires of greater intensity.5

California’s Insurance Commissioner, Ricardo Lara, followed suit: “The actions announced today are aimed at addressing problems fueled by climate change . . .”. The national media, already deeply dependent upon climate porn, readily follows along, and voila, we have a climate-fueled insurance crisis.

There is a glaring irony here — Let’s say that the challenges facing insurance are indeed being driven by a long-term change in the statistics of weather (i.e., the definition of “climate change”). If so, then the solution would be obvious — just increase insurance rates to align with the newly estimated risks of loss. That is the bread and butter of insurance.

Problem solved.

Of course, the issues here are not about managing risk via climate policies but pricing. Implementing more actuarially sound rates — whether reflective of changing climate risk or changes to exposure or vulnerability — will necessarily result in higher insurance rates for homeowners and a likely widespread decrease in property values.

For politicians, it is much easier to say that climate change did this to their constituents, not bad public policy.

But disasters happen and, always, someone has to pay. Rather than fix Proposition 103, California policymakers instead utilize a public backstop called the Fair Access to Insurance Requirements (FAIR) Plan. The FAIR plan uses government funds (paid by the public in taxes) and in extreme cases, levies on insurance companies passed on to consumers, to cover gaps in private insurance coverage resulting from insurance rates that do not correspond to risk.

So everyone pays for the policy failure and the actuarial inefficiency persists unaddressed. Socializing disaster losses also short circuits the ability to use insurance pricing to send signals via the market to consumers about the risks of development and homeownership in risky locations. Such price signals can motivate homeowners and developers to employ wildfire mitigation.

Grep Ip, chief economics commentator at the Wall Street Journal (and without a doubt the top national reporter on this issue), explains the situation clearly:6

Earlier this month, JPMorgan estimated the fires around Los Angeles had inflicted $50 billion in losses, of which only $20 billion were insured.

One reason for the gap: State regulators have prevented insurers from charging premiums commensurate with rising property values, construction costs and wildfire risk exacerbated by a warming climate. Many thus stopped renewing policies.

Hundreds of thousands of homeowners shifted to California’s state-run backstop, the Fair Plan, whose exposure has tripled since 2020 to $458 billion. It has only $2.5 billion in reinsurance and $200 million in cash.

If the Fair Plan runs out of money, it can impose an assessment on private insurers to be partly passed on to all policyholders. In other words, the costs of the disaster will be socialized.

Improving the insurance situation will not be politically easy.

No one wants higher costs, and for many, the imposition of higher insurance rates that more accurately approximate risk would result in a loss of equity in their home or even make continuing to live in their home economically impossible.

Societal upheaval would result and politicians would inevitably pay a high political price for imposing such changes.

At the same time, the current situation is unsustainable — The laundering of the insurance backstop through FAIR may have reached a limit with the recent fires.

A positive path forward would first acknowledge the underlying problem here — policy not climate. California could set a long-term goal, say 20 years, to realign insurance regulation with more sound actuarial pricing. As that releveling occurs, it will continue to be necessary for the public to backstop insurance during the transition.

California’s insurance crisis is the result of democracy — a poorly designed citizen’s initiative approved by voters almost forty years ago. Fixing crisis will require more democracy, meaning sustained public support for getting out of this predicament together and elected officials willing to tell the truth.

The most simple thing you can do to support THB is to click that “♡ Like”. More likes mean the higher this post rises in Substack feeds and then THB gets in front of more readers!

This article oringinally appeared on Roger’s Substack, The Honest Broker. If you enjoyed this piece, please consider subscribing here.

1 In The Wealth of Nations (1776), Adam Smith wrote: “The trade of insurance gives great security to the fortunes of private people, and, by dividing among a great many that loss which would ruin an individual, makes it fall light and easy upon the whole society. In order to give this security, however, it is necessary that the insurers should have a very large capital. Before the establishment of the two joint-stock companies for insurance in London, a list, it is said, was laid before the attorney-general, of one hundred and fifty private usurers, who had failed in the course of a few years.”

2 The group that championed Proposition 103 is today called Consumer Watchdog, and you can read their view of the legislation here. For a counter view, see NAIMC.

3 An actuarily sound rate is one where the pricing of insurance accurately approximates risk.

4 Under the IPCC definition of climate change, climate change (a change in the statistics of weather) cannot be detected over a period as short as 20 years.

5 In the EO, Newsome also blames California’s recent winter storms on climate change.

6 Worth noting that Greg Ip is an economics reporter, and not on the “climate beat.”