Today, The Washington Post and New York Times have both reported that any day now, the Trump administration will publish a proposed rule that reconsiders the 2009 greenhouse gas “endangerment finding” by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). In anticipation of the proposed rule’s release, today I highlight five things that everyone should know about the “endangerment finding” so that when we have the proposed rule in hand, here at THB we can hit the ground running.

The proposed reconsideration is unlikely to be about climate science

The NYT reports:

In calling to repeal the endangerment finding, the draft E.P.A. rule does not appear to focus on the science or try to make the case that fossil fuels aren’t warming the planet.

While many seem to want the issues here to be about climate science, they are not.

Consider that in Justice Roberts dissent in Massachusetts v. EPA (2007) — the Supreme Court case that ruled that EPA was required to issue an endangerment finding under the Clean Air Act — Roberts did not dispute any aspect of climate science:

Global warming may be a “crisis,” even “the most pressing environmental problem of our time.” Pet. for Cert. 26, 22. Indeed, it may ultimately affect nearly everyone on the planet in some potentially adverse way, and it may be that governments have done too little to address it.

Roberts focused on the legal and statutory issues instead. As well, in his dissent in the case, Justice Scalia explained that his perspective was also grounded in law, and not climate science:

The Court’s alarm over global warming may or may not be justified, but it ought not distort the outcome of this litigation. This is a straightforward administrative-law case, in which Congress has passed a malleable statute giving broad discretion, not to us but to an executive agency. No matter how important the underlying policy issues at stake, this Court has no business substituting its own desired outcome for the reasoned judgment of the responsible agency.

The Clean Air Act sets the scientific standard for an endangerment finding as a very low bar:

The Administrator shall by regulation prescribe (and from time to time revise) in accordance with the provisions of this section, standards applicable to the emission of any air pollutant from any class or classes of new motor vehicles or new motor vehicle engines, which in his judgment cause, or contribute to, air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare.

The key word there is “shall.”

The endangerment finding in place today exists based on a previous EPA administrator’s judgment that greenhouse gas emisisons “may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare.”

Once that judgment was made it took on a precedential status, meaning that to reverse that judgment would require a subsequent EPA administrator to conclude that GHG emissions “may reasonably be anticipated NOT to endanger public health or welfare.” Proving the negative formulation of that clause invokes a much higher standard of scientific evidence, and likely an impossible one to meet.

Of course, there are some with legitimate beliefs that GHG emissions are indeed harmless. However, the existence of such views does not negate the views of others who believe that GHG emissions are harmful. The courts will not (and should not) arbitrate these views, but will simply note that the large body of research suggesting risks associated with changes in climate due to GHG emissions is a sufficient basis for a reasonable anticipation of endangerment.

Thus, I expect the reconsideration to be about law and not about science.

The CAA definition of “air pollution” is unambiguous and bipartisan (surprise!)

Writing in his dissent in Massachusetts vs. EPA in 2007, Justice Scalia argued that under Chevron deference, the Court should defer to EPA to interpret Clean Air Act’s definition of “air pollution.” Scalia argued that the majority’s “reading of the statute defies common sense.” Justice Scalia explained:

As the Court correctly points out, “all airborne compounds of whatever stripe,” ante, at 26, would qualify as “physical, chemical, . . . substance[s] or matter which [are] emitted into or otherwise ente[r] the ambient air,” 42 U. S. C. §7602(g). It follows that everything airborne, from Frisbees to flatulence, qualifies as an “air pollutant.”

Justice Scalia is correct that Frisbees and flatulence could indeed be regulated under the CAA, were the EPA administrator to issue an endangerment finding for either. That may defy common sense, but that is an issue for Congress, which has been known on occasion to author legislation that is insufficiently precise.

In addition, the invocation of Chevron Deference is now no longer relevant as the Court recently overturned Chevron, in Loper Bright — meaning that EPA no longer has deference to interpret statutes based on agency expertise.

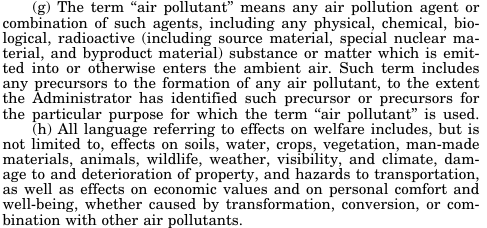

Below is the relevant language of the Clean Air Act that defines both “air pollutant” and “effects on welfare”.

The language is indeed incredibly broad — both for “air pollutant” and for “effects on welfare” — but it is also, as Justice Stevens argued in his majority opinion in Massachusetts versus EPA, “unambiguous.”

Should the Trump administration wish to challenge the definition of “air pollution” and whether it legally encompasses GHGs, they will certainly run into some high legal hurdles.

For instance, I suspect some might be surprised to find an Easter Egg in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, President Trump’s recent signature legislation — it refers explicitly to “greenhouse gas air pollution.”

Similarly, the Inflation Reduction Act, President Biden’s signature legislative accomplishment, defines greenhouse gas as follows:

In this section, the term ‘‘greenhouse gas’’ means the air pollutants carbon dioxide, hydrofluorocarbons, methane, nitrous oxide, perfluorocarbons, and sulfur hexafluoride.

In recent years, both parties voted almost unanimously to classify GHGs as “air pollutants.” Congressional intent here is not ambiguous.

Congress could of course enact legislation with a different definition of “air pollutant” — it is highly unlikely that the courts would depart from enacted legislation. So efforts to reinterpret “air pollutant” are unlikely to succeed, in the absence of new legislation.

Addressing GHG regulation, stronger or weaker, will require Congress to act

Any proposed reconsideration of the EPA endangerment finding is likely to wind up in the courts. If the issue made its way to the Supreme Court, it seems likely that it might have a chance to be upheld, given that most Republican-appointed justices are on record opposing the verdict of Massachusetts versus EPA.

However, there is no guarantee that any case would be resolved before the next presidential election, and even if so — the Trump administration’s reconsideration itself would likely be re-reconsidered by the next Democratic administration.

Such regulatory policy ping-pong is no way to implement regulations governing energy policy, which is fundamental to the success of the entire U.S. economy. We have here yet another example where partisan politics has pushed aside policy pragmatism.

Congress could readily end the policy ping-pong by amending the Clean Air Act to carve out precise language governing greenhouse gas emissions, as a category of regulation separate from conventional air pollution.

There are ways to write such language to be more consistent with the aims of the Trump administration or the goals of the climate lobby. However, either approach is likely to be dead-on-arrival in the sharply divided Congress, meaning that compromise would be necessary.

I know compromise is a dirty word in contemporary U.S. politics, but let’s dream on a bit.

Compromise language could aim for a sweet spot where the regulation of greenhouse gases is recognized as legitimate, but also is required to be subject to clear technological or economic criteria. For instance, the CAA requires the use of “best available” technologies for pollution control meaning the regulator, “on a case-by-case basis, taking into account energy, environmental, and economic impacts and other costs, determines is achievable for such facility through application of production processes and available methods, systems, and techniques.”

Similar language could be applied to the regulation of GHGs in a way that hits a bipartisan sweet spot, and creates regulatory certainty in energy policy for decades to come. In fact, finding that sweet sport is the main job of Congress.

Expect a lot of hyperbole

The Trump administration’s actions will no doubt be variously characterized as the best thing since sliced bread, or the initiation of the end of times. Buckle up.

For instance, in its reporting today the New York Times claimed that a reconsideration of the EPA “endangerment finding,”

. . . would prevent future administrations from trying to tackle climate change, with lasting implications.

That is simply false. Climate policy ping-pong is well into its third decade.

Commenting on the NYT article, U.S. Representative Sean Casten (D-IL) Tweeted on X hyperbolically:

. . . when the history of this era is written, Donald Trump will have been responsible for more deaths than Stalin, Mao and Hitler combined.

According to ChatGPT that implies more than 100 million deaths.

That’s silly.

Expect more false and silly claims, and from both sides.

My views

Here are my views, from a February THB post, which explores each in detail:

- From both a legal and scientific standpoint, there is no legitimate basis for rescinding the 2009 “endangerment finding;”

- From a create-chaos standpoint, the Trump administration may choose to rescind the finding and set in motion a dispute to be adjudicated by the courts;

- There are good reasons, scientifically, to update the “endangerment finding,” as more than fifteen years have now passed and its justifications are out-of-date;

- If the Trump administration (or really anyone) wants to improve climate policy in line with U.S. national interests, then it should engage Congress, including proposing revisions to the Clear Air Act.

I also recommend this analysis today by Jonathan Adler, Tazewell Taylor Professor of Law at the William & Mary Law School: EPA Embarking on Endangerment Finding Fool’s Errand.

Mark your calendars — On September 17th at AEI in Washington, DC, I’ll be joining my colleague Benjamin Zycher and several other panelists, to discuss and debate the endangerment finding. The panel will have a robust diversity of views.