I am the answer to a trivia question.

Who is the only person to appear in the leaked 2009 Climategate emails and in the 2016 Hillary Clinton Wikileaks emails?

That’d be me. At the time, in both cases the leaks revealed efforts to censor my research and damage my career. In both cases I thought — Thank goodness for tenure and academic freedom!

This series has documented how universities have become deeply politicized and as a result, we see significant challenges to academic freedom on campuses across the country. I no longer have the same confidence in academic freedom in universities that I once did. Today, I’ll discuss my recent experiences at the University of Colorado Boulder (CU) in the context of the broader challenges facing universities. My experiences, while extreme, illustrate the real professional consequences of the politicization of the American university.

Before jumping in, a bit of throat clearing — This month, as I end almost 24 years as a tenured, full professor at CU, I look back at my experiences with a lot of happiness and strong sense of accomplishment. My track record as a professor is pretty damn good, if I say so myself. I don’t really feel like I’m leaving the university — the university left me.1

As you read about my experiences you’ll notice that I don’t include anyone’s names.2 That is intentional. I describe an institutional failure as seen from my perch. Sure, institutions are led by people, but the failures I describe are systemic. Any one of more than two dozen administrators (defined as department chair on up) could have easily dealt with the issues I discuss below. None did. Some even targeted me with a goal — in my opinion — of forcing me out.

One reason why I am comfortable sharing details that I’ve never before discussed in public is that my experiences at CU are not at all unique to me. Other faculty at Colorado have recently experienced administrative discipline and diminishment of their roles, seemingly as punishment.

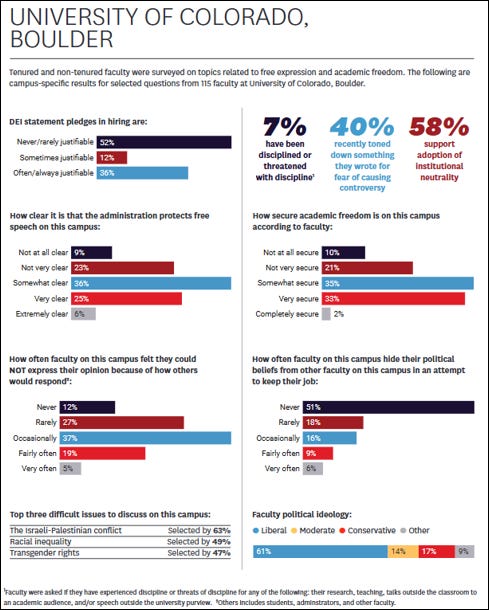

More broadly, a survey of faculty just released by Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) indicates that 7% of CU faculty report been disciplined or threatened with discipline associated with their teaching, research, or expression — See the figure below.3 Almost a third of CU faculty believe that academic freedom is not very or not at all secure at CU. These are not figures indicating a health academic workplace. My experiences bear this out.

The perception of a highly politicized workplace among CU faculty are representative of how faculty see their universities across the country. Among FIRE’s survey of 6,269 faculty at 55 major colleges and universities:

- Nearly half of conservative faculty (47%) report they feel unable to voice their opinions because of how others might react, compared to only a fifth of liberal faculty (19%).

- A third (35%) of faculty say they self-censor their written work, nearly four times the number of social scientists who said the same in 1954 at the height of McCarthyism.

- 87% of faculty reported finding it difficult to have an open and honest conversation on campus about at least one hot button political topic.

Grab a cup of coffee. Settle in. Let me tell you4 about my recent experiences . . .

At CU, everything changed for me in 2015 when Congressman Raul Grijalva (D-AZ) asked my university to investigate me — He alleged that Obama White House criticism of me indicated that I may have been secretly taking money from Exxon in exchange for the substance of my Congressional testimonies, in which I reported consensus scientific findings of the IPCC (but I digress).

Of course, I was not taking money in exchange for testimony or anything else. What was odd — to me at least — was that after the investigation was announced and conducted, no campus administrator ever spoke to me about it, not even to check in and see how I might be doing. I only heard from university lawyers.

Not long after, I was told that university support for the science policy center that I had been recruited to CU to found in 2001 could no longer be guaranteed, and the center might be closed. No one linked this explicitly to the Grijalva investigation, but I could not help but think they were related.

Sensing that the issue was really me, I chose in 2015 to leave the science policy center and the university institute that it was a part of to go across camps and create a new sports governance center — focused on another of my intellectual passions and far from the reach of the climate police. I had hoped that my leaving the science policy center would allow it to continue while I continued to do excellent teaching, research, and university service in another fascinating area where science meets politics.

Thanks to enthusiastic support from two successive athletic directors, the university allowed me to move into the Athletic Department to develop the new center. For four years things went great — I created and taught a hugely popular undergraduate class, developed with colleagues a novel proposal for a new professional masters degree program, produced collaborative world-leading research, engaged a great group of university and international collaborators, and the center received national and international attention.

Meantime, as I was expanding a new career focus in sport governance, across the campus CU faculty and administrators began moving the institution headlong into climate advocacy.

In 2016, the Boulder Faculty Assembly — the primary governing body of the faculty — led by a professor of Environmental Studies (ENVS)5 adopted a generic and highfalutin statement in support of institutional campus climate advocacy:

Whereas this strong and consistent evidence demands urgent action now, in the context of demands for action from leading businesses, universities, governments, and civil society around the world; be it therefore

Resolved, that we encourage our campus community to work constructively, using our human ingenuity, creativity and collaborative capabilities, to confront and support solutions – including mitigation and adaptation – to address the effects of changes to our global and regional climates.

The activist faculty were just getting started.

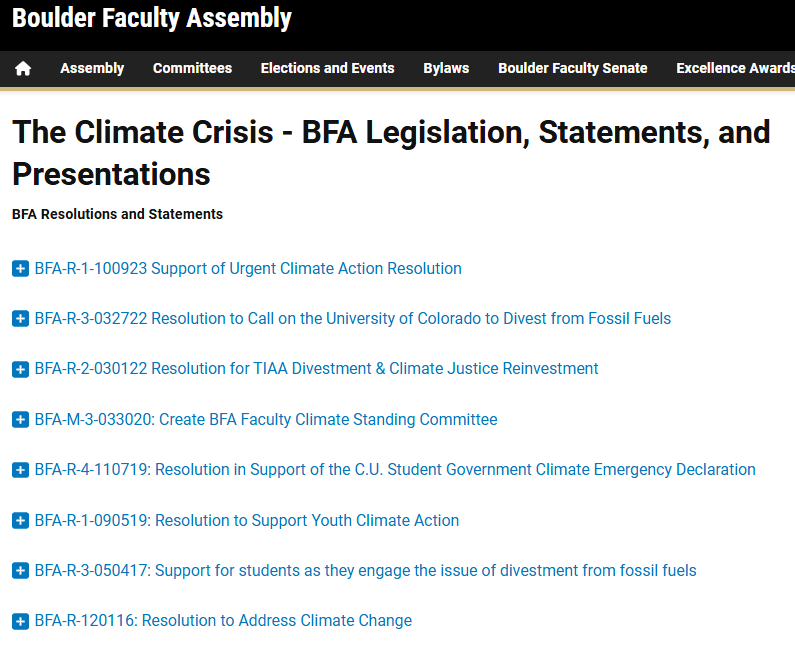

Over the next seven years, the faculty assembly issued 8 statements and resolutionscalling for climate advocacy on campus — including encouraging students to engage in nonviolent “confrontations” and joining with student activists and external NGOs to declare a “climate emergency.”

All of this might have been laughed off as a handful of self-important professors role-playing as world leaders and U.N. diplomats.

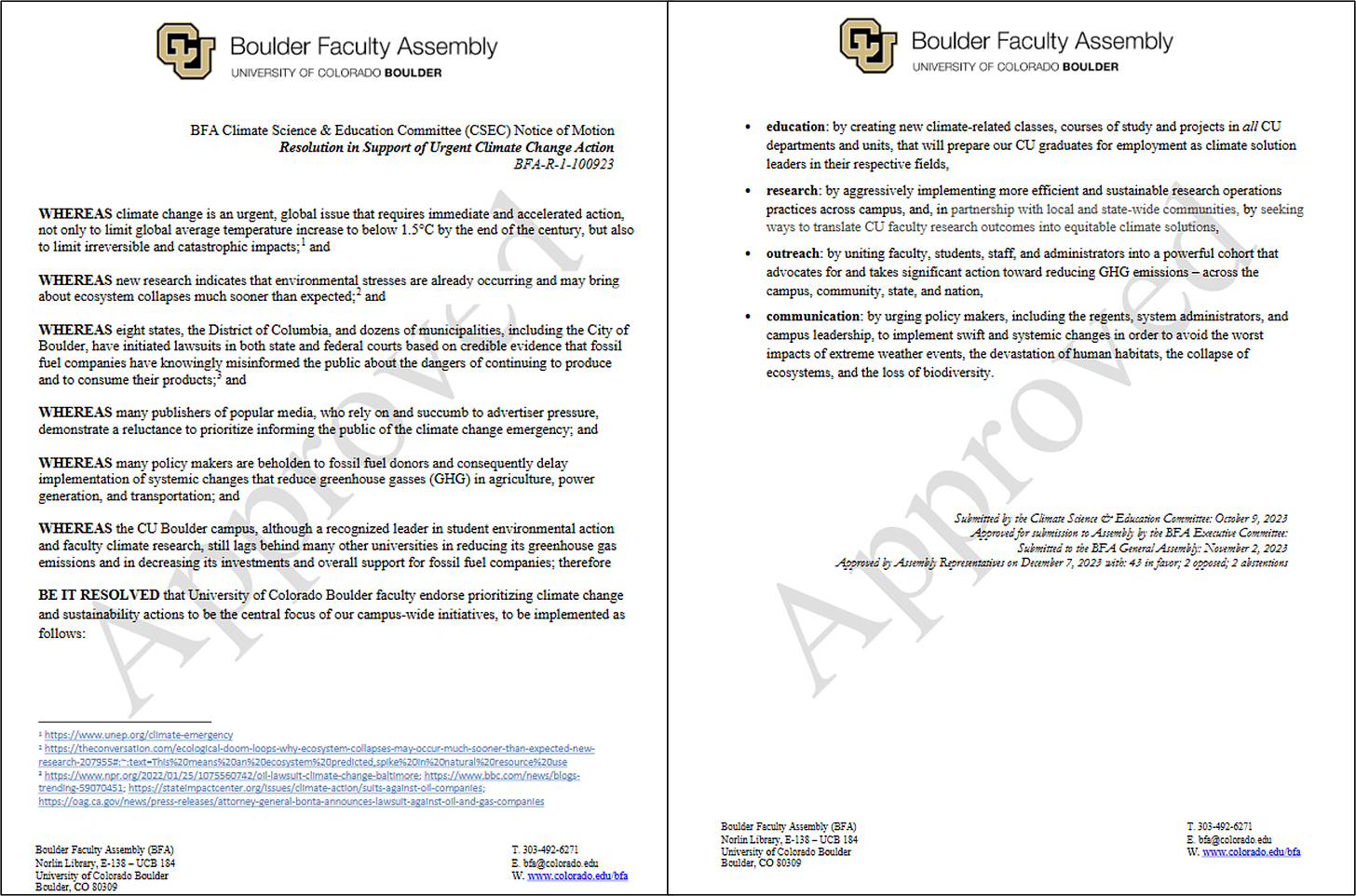

Soon, however, the empty exhortations turned into demands that the entire university morph into a climate advocacy organization. In 2023 the activist professors led a new faculty resolution demanding that the university refocus its mission on climate activism:

BE IT RESOLVED that University of Colorado Boulder faculty endorse prioritizing climate change and sustainability actions to be the central focus of our campus-wide initiatives . . .

This new “central focus” included a demand that climate advocacy be taught in “allCU departments and units” (emphasis in original) and university education prioritize training all students to be “climate solution leaders.”

The resolution — reproduced above — also demanded that,

“faculty, students, staff, and administrators [unite] into a powerful cohort that advocates for and takes significant action toward reducing GHG emissions – across the campus, community, state, and nation.”

The entire campus was to engage in political advocacy,

“[We are] urging policy makers, including the regents, system administrators, and campus leadership, to implement swift and systemic changes in order to avoid the worst impacts of extreme weather events, the devastation of human habitats, the collapse of ecosystems, and the loss of biodiversity.”

This reads more like a mission statement for Greenpeace than it does anything remotely related to the mission of a flagship state university.

In the midst of this turn to institutionalized climate advocacy, in 2020 the university created a new center — the Center for Creative Climate Communication and Behavior Change — focused on “changing human behavior.” The new center’s goals were:

[T]o design and test interventions that nudge and boost people toward sustainable attitudes, beliefs, and behavior that will meet the climate challenge. These include changes to civic action and engagement that supports substantive policy as well as changes to individual consumption.

This new behavior change center — which sounds more like an environmental NGO — was led by the same faculty members behind the faculty assembly statements calling for the entire campus to reorganize around climate advocacy, including the ENVS department chair.

In 2022, in response to faculty demands, the university hosted a climate advocacy conference – the Right Here, Right Now Climate Summit. This “summit” emphasized celebrities (below), activists, and plenty of exhortations to political action. There was no obvious connection to the university’s actual mission.

During this time that the university was turning up the dial on climate activism, changing the institution in the process, I was teaching, researching, and building the nation’s first academic unit housed in a major Division 1 athletic department. I was generally unaware of the degree to which climate advocacy was becoming core to the campus mission.

For me, things were going great, or so I thought.

For reasons never made clear to me, the experiment in marrying academics and athletics ended in 2019 — after four years — when campus administrators decided to halt further development of the sports governance program.6

Rather than return me to the campus institute where I had previously been rostered (as was in the terms of the memorandum of understanding that transferred me to CU Athletics), administrators instead placed me into the ENVS department.7 In the process, the university doubled my teaching load from that in my original contract.

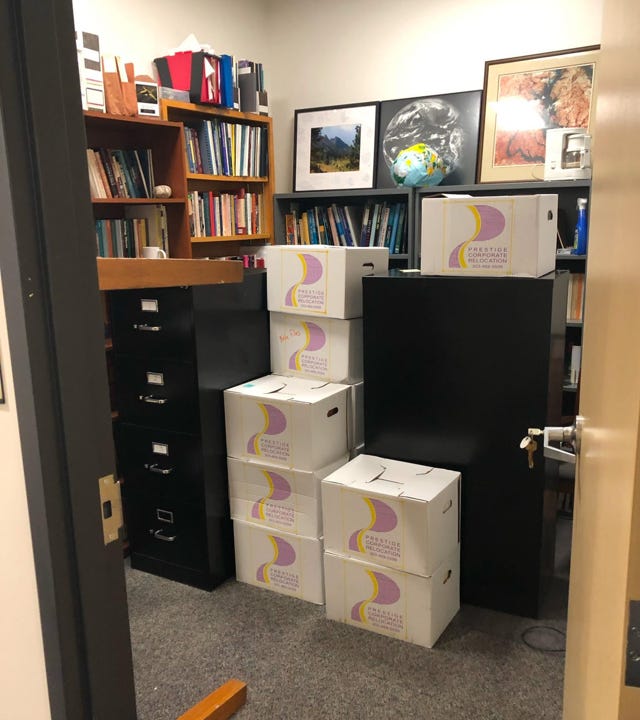

ENVS placed me into small, windowless room previously used for storage (and labeled as such on the building plans) deep in the bowels of the soulless building in the office park where the ENVS department was located, about one mile east of the main campus. My little office was far removed from other ENVS faculty and the ENVS office.

OK, I thought, I’ll make this work — I set up shop in the storage space and committed to continue to conduct excellent research and to teach excellent classes.

In 2020, the university finally terminated the science policy center that I had created and led. A little later, the university also decided to terminate the graduate certificate in science and technology policy that I had established. Both termination decisions — ironically enough — were apparently made by the climate campaigning ENVS professor, who was also happened to be the chair of the department that was now my campus home.

A decision was made that all eight graduate courses that I had developed and taught as part of the graduate certificate program were no longer to be offered — This meant that all of the classes I had been recruited to Colorado to develop and teach were no longer being offered.8

I requested of the ENVS chair that I take complete responsibility for leading the continuation of the science policy center (I even found an external partner) and that I would again oversee the S&T graduate certificate program — but he told me no, absolutely not, he would not allow me to do that.

Over the next few years, I was repeatedly told to develop and teach new undergraduate courses, with new requests just about every semester — In academic parlance: nine new preps in four years (one of those years was a sabbatical, whew). For example, I taught a fun and popular upper division energy policy course that received rave reviews from students — tripling the class size in just two years, after which I was permanently removed from teaching it.

I rolled with it. What was the alternative?

In mid-2020, I was told that the university was going to use my little office for storage of a large number of boxes and several file cabinets that were not mine (but apparently were connected with the science policy center I had left 5 years earlier). The storage of these items rendered my little office completely unusable, as you can see above. I never touched them — mainly out of fear that I’d be accused of something nefarious if I did.

Later we learned that the file cabinets stored in my office were actually empty. Funny!

As the pandemic unfolded in 2020 it was clear that having a usable office on campus was not actually that big a deal, as everyone was remote. So I let it ride.

But in 2021, after we returned to campus I mentioned the unusable office to everyone who would listen — and I guess, also to some that didn’t — requesting that the situation be fixed. Nothing was done for years. My faculty colleagues were aware and many were sympathetic, but the ENVS department chair did not budge.

Around the same time, as fall 2020 started, the ENVS department chair placed me under investigation.9 Bizarrely, he accused me of winning a NSF grant (for the EScAPE project) in violation of university procedures.

I’m not sure how one might get a grant outside university procedures (I did not) so the accusation was quite obviously a sham.10 But he went through with an investigation that spanned almost a year, empaneling some cronies to write a report, and finding me guilty of something or other and sanctioning me — which I guess was just a strongly worded letter in my permanent file.

But he did throw around phrases like “possible termination” and such, and strangely, administrators acted like they were taking it seriously, so I took it seriously as well.

I appealed the sham investigation and sanction to a faculty committee from outside my department which found no factual basis for the investigation and that my due process rights may have been violated. Oh. There was no consequence for the ENVS department chair for bringing the false allegations.

Soon after I was the subject of yet another investigation (technically an “inquiry”) because I had shared with colleagues that I had been the subject of the earlier sham investigation. This inquiry was apparently instigated by another one of the faculty members at the “behavior change” climate center. I have no idea what became of this.

As this harassment was playing out, on many occasions I asked campus administrators to either implement a formal process of mediation with my department chair or to find me a new home on campus where I was not subject to a hostile work environment.

Administrators did neither for three years — but lucky for me, for one of those years I was overseas on a wonderful sabbatical at the University of Oslo, where I could leave these issues behind.

In 2023, soon after I returned from the sabbatical, a new dean of the College of Arts and Sciences (who I’ve never met) finally decided to move me out of ENVS, but for some reason did not place me into a new unit. I was given an office (with a window!) in the stadium — which housed an island of misfit toys worth of academic programs. For a short moment everything seemed to be looking up.

Then they didn’t.

In what must be some sort of joke from the university gods, the new office I was provided was rendered unusable for about a year because the campus was installing a new gigantic video screen on the south end of the stadium, directly over my office. I was given several days’ notice about the lack of access— right before Christmas 2023 — and not provided any alternative space on campus.11

So at the start of 2024, I found myself with no future courses to teach,12 no space on campus, no home academic unit, no university service, no way to obtain basic administrative support much less prepare, submit, and oversee grants for research funding, no possibility of having graduate students, and no way to address any of this on my own. I contacted many departments and units to see if I could secure a home on campus, with some showing interest, but with absolutely no upper level support for finding me a campus home, I had no luck.13

Rightly or wrongly, my thinking was that the university was prepping to oust me, despite my having tenure and an outstanding track record, by claiming that I was not fulfilling my job duties of teaching and service. Of course, the campus had made that impossible.

I considered just going with it — showing up to my office in the stadium, collecting a paycheck, and being a unit of one person with no teaching or service. There is probably a joke to be made here involving George Costanza and his job at the NY Yankees!

Instead, more than nine years after my university first investigated me at the request of Congressman Grijalva, I finally took the hint — CU administrators did not want me on campus and they were going to turn the screws until I left.

So earlier this year I chose to retire. And I am glad I did — not just because of what I’m leaving behind, but also because of what lies ahead.

Other than various procedural paperwork associated with retiring, in my final semester after almost 24 years, I have heard nothing from any administrator on my campus. I didn’t expect a gold watch, but an email might have been nice.14

Was the harassment and hostile work environment since 2019 connected to the Grijalva investigation or the institutionalization of climate advocacy on campus?

I have no idea, but I have suspicions.

Was the apparent vendetta against me by the climate campaigning chair of the ENVS department motivated by his politics or his perceptions of mine?

I have no idea, but I have suspicions.

What I do know is that academic freedom and tenure mean little without administrators who stand up for their faculty when they are under attack — whether from inside or out, whether from the left or the right. When a university institutionalizes political advocacy, it grants a green light to campaigning faculty and administrators to come after those colleagues who they view as their political enemies, misusing the policies and procedures of the institution to do so.

I am incredibly proud of my track record of teaching, research, and service at the University of Colorado Boulder, and I look forward to serving as an emeritus professor for many years to come. I expect that the fever of climate advocacy at CU will break at some point and mainstream views such as mine might again be welcome on campus.

Make no mistake — what happened to me was wrong, and should not happen to any faculty member. The data from FIRE released this week suggests that my experiences are unfortunately not at all unique — at Colorado or elsewhere. Next week Ill wrap up this series with some practical recommendations for how universities can correct course and get back on track.

The easiest thing you can do to support THB is to click that “♡ Like”. More likes mean the higher this post rises in Substack feeds and then THB gets in front of more readers!

1 I am absolutely thrilled to have joined the American Enterprise Institute as a Nonresident Senior Fellow earlier this year. Starting in January, I will also be an emeritus professor at CU, which was recently approved by a unanimous vote of the relevant faculty committee. I awaited writing this post until that decision was announced to me.

2 I do not want any comments about any individuals in the comments here. Thanks.

3 I was not a participant in the survey.

4 Note that every claim I make in this piece can be backed up and supported with contemporary documentation.

5 ENVS was the unit where I had taught from 2001-2015, before starting up the sports governance center.

6 If the campus had let this experiment continue, I’d likely still be doing sports governance.

7 There is an apparently more sinister detail to note here — When the university moved me to Athletics, unknown to me, they removed me from my tenured faculty line and placed me on what is called soft money. The campus then hired a replacement faculty member in my line. I learned of this only in 2019, after the campus decided not to continue supporting development of the sport governance center, and — surprise — I found out I was no longer employed by the university. Obviously, they couldn’t do that to a tenured professor — I guess someone did not really think that through. A new line was found. But for me, it suggested that administrators had been expecting me to leave and did not have my best interests in mind.

8 My original contract with the university specified that I was to emphasize teaching at the graduate level and to develop new graduate offerings related to science and technology policy.

9 With hindsight, the fact that I started The Honest Broker here on Substack in October, 2020 must have been a subconscious effort at opening up opportunities beyond CU. I could never have guessed where that would lead!

10 Honestly, if one is going to conjure up a false accusation for which to investigate a colleague, I’d think there are more creative options than this!

11 I finally regained access to this office in fall 2024, just in time to pack up my books.

12 In spring 2024 I taught the final class for ENVS that I had been assigned — a senior capstone, and it was a great group of students. Over my 24 years I never once had any issues with students — They welcomed our discussions of complex issues, whether climate change or transgender athletes. My experiences are that the students are far less political than the faculty.

13 A bit of inside baseball — Some departments and units on campus showed interest in having me join them but uniformly expressed concern that taking me in would count against their receiving a future faculty line, which none wanted to risk surrendering. Administrators could have just placed me into one of many possible units — they chose not to.

14 I am happy to report that the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), where I began my career, has agreed to take all of my books and reports related to climate and weather, establishing the Roger Pielke Jr. collection. The American Enterprise Institute (AEI), where I’ll be for the foreseeable future, has agreed to take all of my books on political science, public policy, economics, and science and technology policy to add to their library.