In the annals of history, the first half of 2025 will be remembered for many things. I’d venture that very few are aware of one of the most momentous achievements in human history occurred in the past six months.

In fact, there is an organized effort to keep you from understanding this achievement. Before getting to that effort, let’s first take a look at some remarkable new data on the impacts of weather on people.

Over the weekend, I was reading the Aon Global Catastrophe Recap, First Half ((1H) of 2025.1 In terms of economic losses, the first half of the year was overwhelmingly dominated by losses in the United States (especially the California fires) accounting for more than 90% of total insured losses (~$100 billion).

What really jumped out to me was this conclusion:

At least 7,700 people were killed due to natural disasters during the first half of 2025, which is well below the 21st-century average of 37,250. Majority of the deaths (5,456) occurred as a result of the earthquake in Myanmar.

That means that ~2,200 people worldwide died in catastrophes related to extreme weather events during the first six months of the year.

On the one hand, ~2,200 deaths are a lot and every loss of life is tragic. On the other hand, in the context of historical losses related to weather extreme, on a planet of 8.2 billion people, ~2,200 deaths is incredibly low. Historically low, in fact.

It is likely that the first half of 2025 has seen the fewest deaths related to extreme weather of any half year in recorded human history

To place this number into context, I immediately went to the EM-DAT database of catastrophe losses, overseen by the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) in Belgium.2 CRED also shows a very low tally of deaths from disasters for the first half of 2025.3 The EM-DAT total is less than that of Aon, so I’ll use the higher Aon numbers in the figures below.4

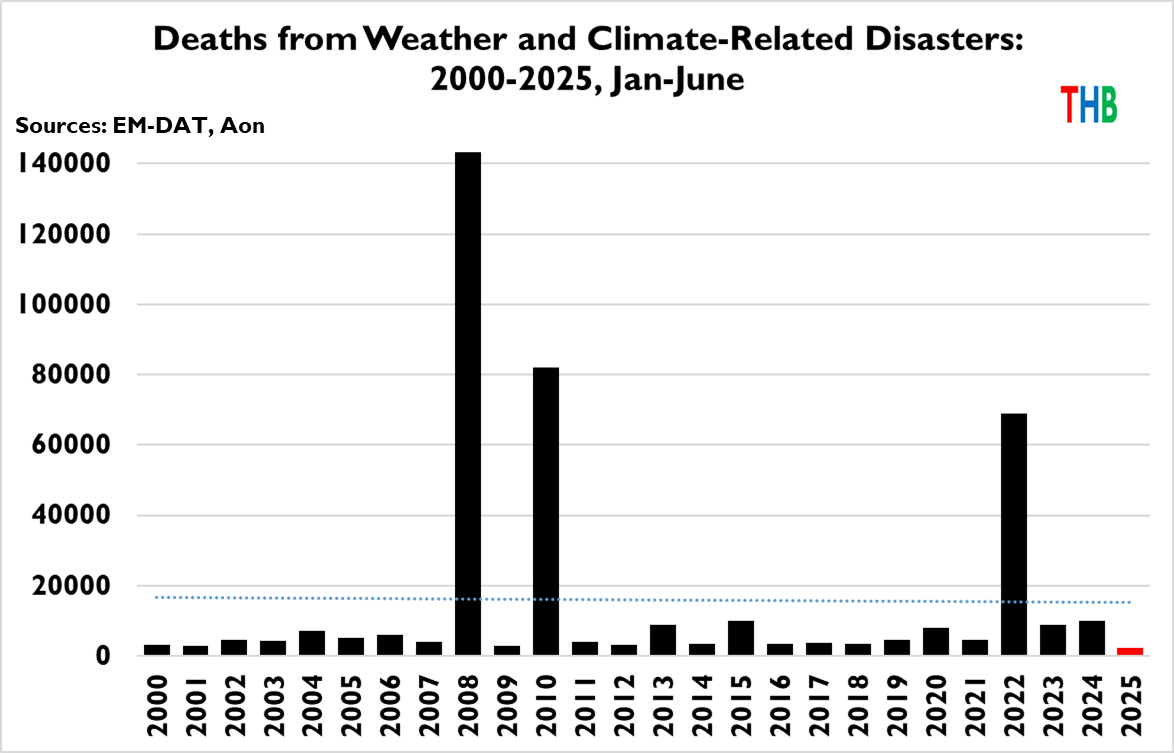

The figure above shows deaths from weather and climate disasters, from January to June, from 2000 to 2025. You can see that deaths are dominated by years with large events — 2008, Cyclone Nargis (~138,000 deaths, Indian Ocean); 2010, heat wave (~56,000 deaths, Russia); 2022, heat wave (>50,000 deaths, Europe).5 The little red bar on the far right of the bar graph is 2025.

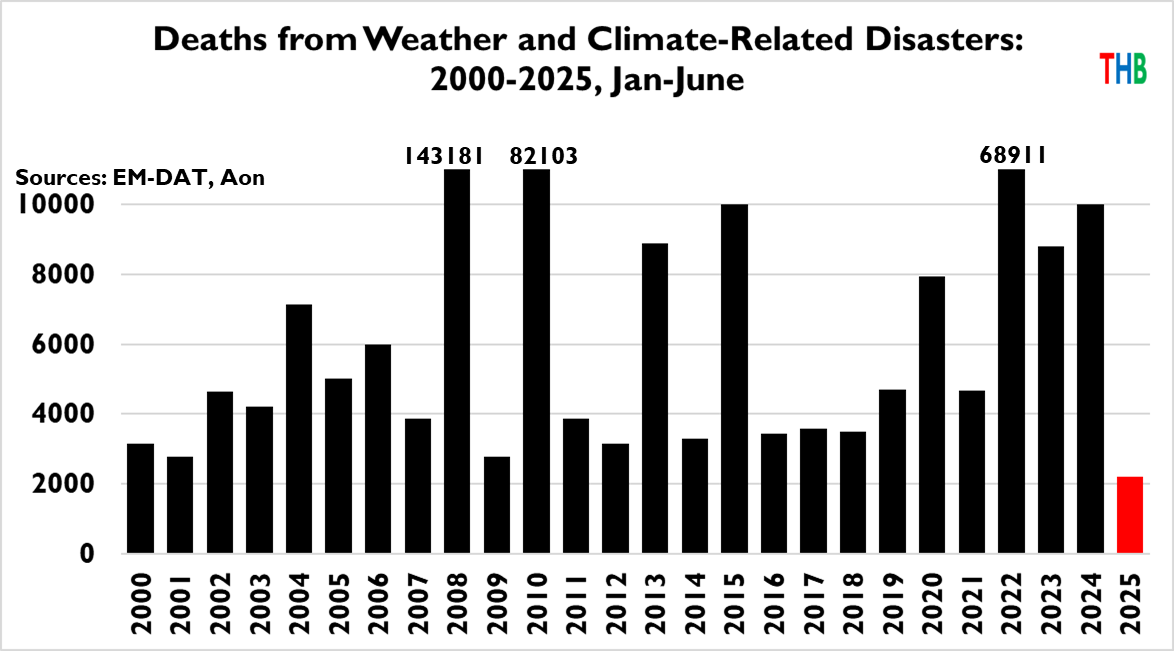

To see 2025 more clearly, I have zoomed in on the graph, shown below.

You can clearly see that 2025 comes in well below any year of the past 25 years. Thus, we can conclude with some confidence that the first half of 2025 has seen the fewest deaths related to extreme weather of any January-June this century.

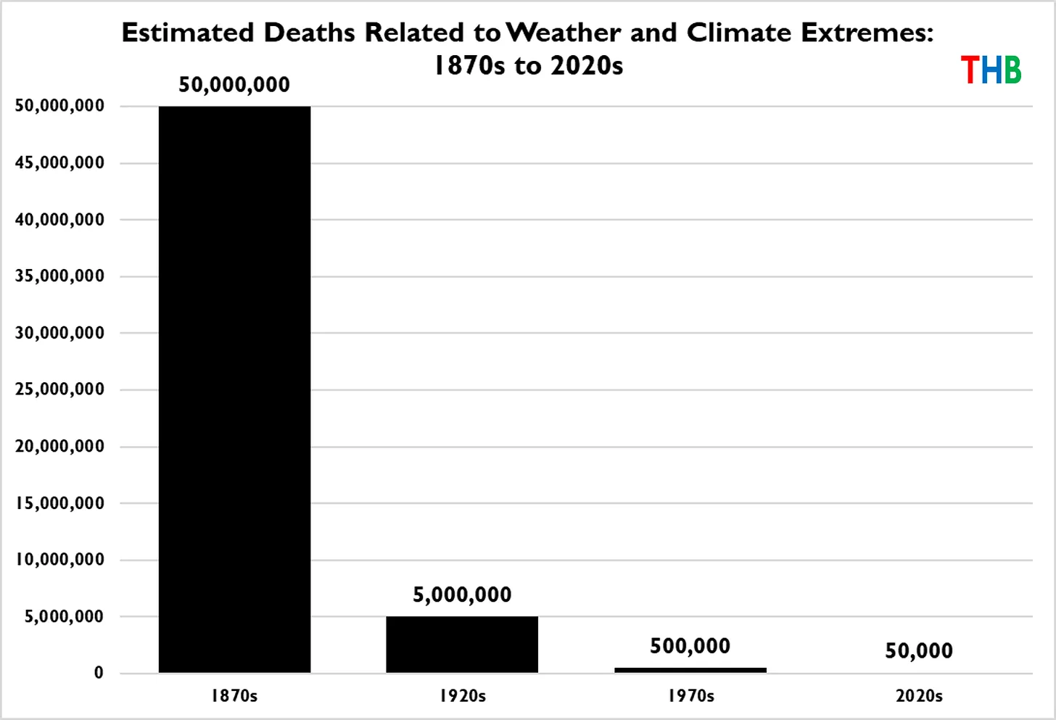

I’d go so far as to suggest that it is likely that the first half of 2025 has seen the fewest deaths related to extreme weather of any half year in recorded human history, given how large losses were in decades and centuries past, as you can see below.

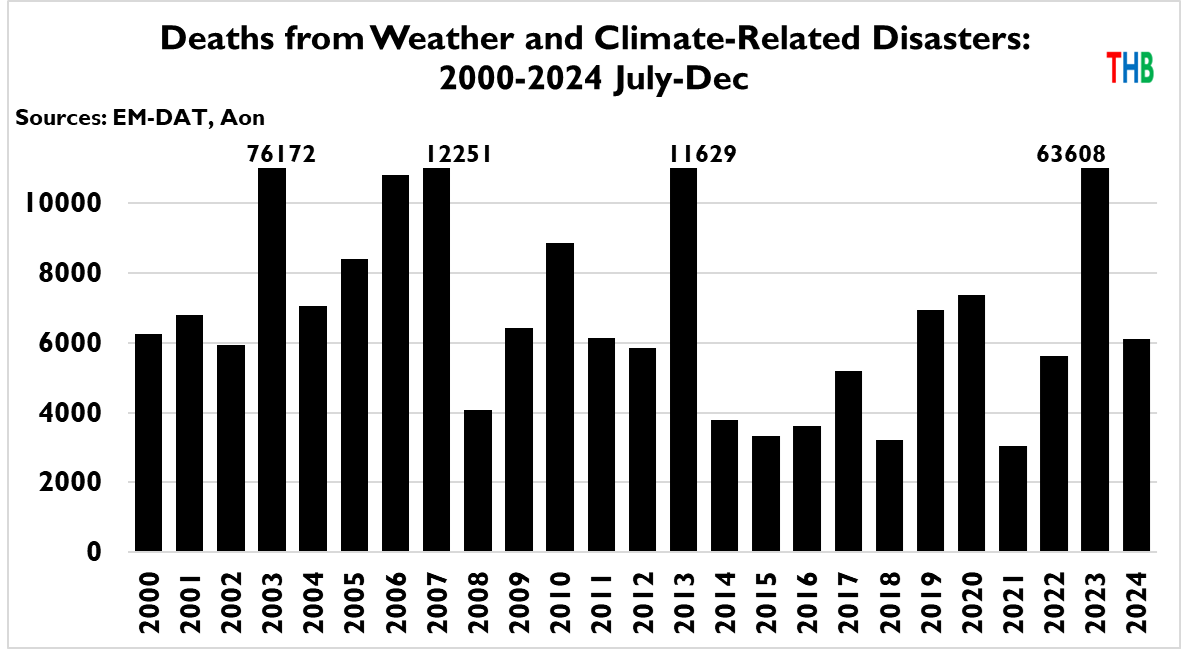

The put the 2025 first half numbers into context, we can also look at deaths in the second half of each year this century, shown below and zoomed in as above.

The first half disaster deaths of 2025 are also lower than any second half deaths in any year this century.

Some additional context:

- This century, during Jan-Jun ~408,000 people died related to extreme weather;

- During Jul- Dec the total is ~288,000;

- In 2000 (July 2000 to June, 2001), the global death rate related to extreme weather was ~1.4 people per million;

- in 2025 (July 2024 to June 2025), the global death rate related to extreme weather was ~0.9 people per million.

- The decrease in global death rates related to extreme weather from 2000 to 2025 was ~60%;

Of course large losses of life related to extreme weather are still possible — and perhaps even likely if we do not emphasize disaster risk reduction.

However, make no mistake — the incredible progress in the reduction of overall deaths from disasters and the even more dramatic reduction in death rates is one of the most incredible accomplishments of humanity on this volatile planet, experiencing change and variability in extreme weather.

You probably haven’t heard much, if anything, about this very good news.

One reason for that is a climate advocacy industry who views their mission as scaring us about the weather to motoivate political change.

For example, last week, CNN’s Harry Enten lamented (emphasis added):

Climate activists have failed to make the case on climate change. Despite all the bad weather, just 40% of Americans are greatly worried about climate change. The same as in 2000. The % who worry about being a natural disaster victim has dropped from 38% in 2006 to 32% now.

Enten apparently views the job of climate activists is to make people “greatly worried” about climate change. Enten is far from alone in this view.

A media association called Covering Climate Now similarly lamented (emphasis added):

Americans Are Concerned About Climate Change—but They Should Be Afraid. Americans still don’t comprehend how imminent, dangerous, and far-reaching the threat is—and journalists are partly to blame.

Covering Climate Now quotes an climate activist in academia to highlight their worry-generating mission:

“I constantly make the point that only 29 percent are very worried, when it should be 100 percent. This reflects [climate change’s] lack of salience for most Americans. There are many who are not deniers, but do not adequately understand the risks, that the impacts are here and now, and the urgency of action.”

Below are some of the 500+ media outlets who have endorsed the Covering Climate Now mission of getting 100% of us very worried about climate change by promoting alarm about extreme weather:

- ABC News

- American Geophysical Union’s Eos Magazine

- Bloomberg

- The Boston Globe

- Christian Science Monitor

- Harvard Business Review

- Miami Herald

- NBC News

- PBS Newshour

- The Weather Channel

- CBS News

Climate advocacy focused on scaring people about their impending doom due to extreme weather is also typically accompanied with a parallel appeal, encouraging them to repent. It is no exaggeration to call this climate evangelism.

Climate evangelism was the explicit message shared last week on LinkedIn by Katheryn Hayhoe, lead scientist of The Nature Conservancy and former head of the U.S. National Climate Assessment.6

Hayhoe quoted and endorsed Pope Leo’s sermon of last week:

“We must pray for the conversion of so many people, inside and out of the church, who still don’t recognize the urgency of caring for our common home. We see so many natural disasters in the world, nearly every day and in so many countries, that are in part caused by the excesses of being human, with our lifestyle.”

Hayhoe argued that the climate movement needs more evangelists like Pope Leo to scare people about the weather to increase support for climate policies (emphasis in original):

After disaster hits, it’s natural for people to ask: What just happened? But unless someone helps connect the dots between that event and climate change, most people won’t link the two—no matter how extreme the weather was.

A new global study looking at nearly 72,000 people across 68 countries found that just experiencing extreme weather wasn’t enough to increase people’s support for climate policies. What did make a difference? Understanding that climate change played a role in making the event worse.

Climate change did it. There is no need for science, for data, for logic. Connect the dots. Spread the good word.

Here is the theory of change at work here: Extreme weather is viewed as resource for creating an atmosphere of fear among the general population. Fear will lead people to demand changes in energy policies that are promised to reduce the risks of weather disasters, and thus address their fears. Research, assessments (like the IPCC), and researchers that don’t play along are viewed to be problematic.

Not only do opinion polls show that this theory of change is misguided as politics, so too does the real world. In contrast to apocalyptic sermons, at no point in human history have humans had less risk of death related to extreme weather and climate. Understanding why that is so is central to keeping that trend moving forward into the future.

Smart energy and climate policies, as I’ve long argued, make good sense. Climate evangelism centered on scaring people about the weather does not make sense — in politics, policy, or science.

1 What can I say? I’m a nerd. Aon has a history of using questionable methods for estimating total economic losses, so I always rely on Munich Re and Swiss Re, whose first-half 2025 recaps have yet to be released. However, there are some positive signs that Aon may be back on track.

2 I see that CRED has newly added an important warning to its database homepage: “Pre-2000 data is particularly subject to reporting biases.” One has to enter a separate portal to access the pre-2000 data. Well done CRED.

3 Specifically in the EM-DAT categories: climatological, meteorological, and hydrological.

4 July entries in EM-DAT do not appear to be yet complete, which likely accounts for the difference.

5 EM-DAT has treated temperature-related deaths inconsistently, which is one reason that here at THB I gave the dataset a yellow light — Use caution. It is appropriate to track excess deaths related to heat and cold extremes, but they should not be lumped in with direct deaths from floods and storms. Far more people die related to anomalously cold conditions than anomolously hot conditions.

6 Hayhoe, while head of the US NCA, once explained on social media that she would never cite my work in the assessment, after blocking me on all platforms. I’m sure she is a perfectly nice person with sincere beliefs, but how such a committed activist rose to the head of the NCA is worth some thought, particularly given the NCA’s total neglect of our widely-cited research.