The U.S. National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) currently has a study committee on Attribution of Extreme Weather and Climate Events and their Impacts. In this series — Weather Attribution Alchemy — I have previously discussed the committee’s many conflicts of interest. Today I discuss a crucial scientific question at the center of the committee’s work, which was raised last week by Noah Diffenbaugh, of Stanford University, in an online information gathering session of the committee.

Diffenbaugh, who is not on the committee but was invited to share his views, asked the following question:1

“I think something that is worthwhile for the committee to grapple with is the broad question of whether single event attribution is even possible at all, from a scientific point of view.”

Diffenbaugh said the quite part out loud. If single event attribution is not possible, then the legal strategy first formulated in a 2012 La Jolla Workshop focused on holding fossil fuel companies accountable for the occurrence of specific weather events and the damage that results completely falls apart — see Workshop on Climate Accountability, Public Opinion, and Legal Strategies.2

There is a lot of confusion about single extreme event attribution. So let’s carefully define what it means.

The IPCC Glossary defines attribution:

Attribution is defined as the process of evaluating the relative contributions of multiple causal factors to a change or event with an assessment of confidence.

The NASEM explains, “attribution refers to causation.” Legal experts have explained that “causation is the Holy Grail of climate litigation” because, in principle, establishing the causes of an extreme weather event (or of making the event more intense) can then be used to assign responsibility to those whose actions caused the event, and thus potentially establish legal liability and compensation.3

As several scientists active in climate litigation explain:

[P]recisely quantifying whose emissions have caused damage to whom, and how much, is critical to advance emerging legal discussions about how courts might apportion liability among the world’s emitters (Burger et al., 2020). Climate change attribution work has long been motivated by the possibility of being used for liability claims . . .

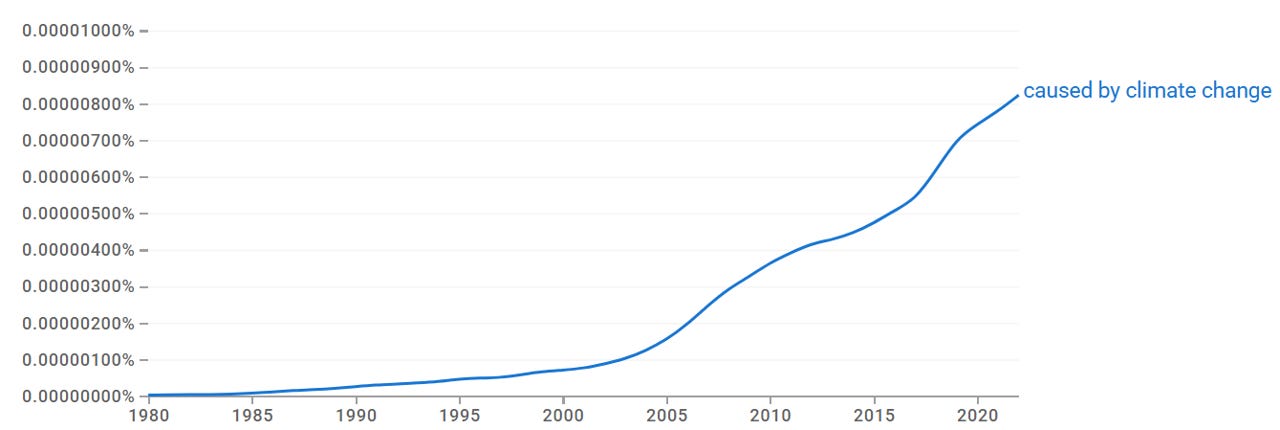

The push for climate litigation against fossil fuel companies is the sole motivating factor behind the rise of the subfield of single extreme event attribution — an example of what I have recently called tactical science.

The fundamental problem with single extreme event attribution — and its a big one — is that it is not scientifically possible, and explaining why this is so is straightforward.

The World Meteorological Organization defines weather:4

Weather is the state of the atmosphere at a particular time, as defined by the various meteorological elements, including temperature, precipitation, atmospheric pressure, wind and humidity.

Single extreme event attribution thus seeks to identify the relative contributions of multiple causal factors to the state of the atmosphere at a particular time. In this context, an specific event is a weather phenomenon that causes damage — a hurricane, a flood, a heat wave, and so on. The litigation motivation necessitates that damage has occurred.

It is critical not to conflate single event attribution with the IPCC’s longstanding framework of detection and attribution of changes in the statistics of weather and climate variables.

The IPCC’s detection and attribution of change follows directly and logically from the IPCC’s definition of climate change:

A change in the state of the climate that can be identified (e.g., by using statistical tests) by changes in the mean and/or the variability of its properties and that persists for an extended period, typically decades or longer.

It is certainly possible to assess observational data and determine that a change in the statistics associated with weather and climate phenomena has been detected and to identify the relative contributions of multiple causal factors underlying that change, including the emissions of greenhouse gases.

Climate change is not a cause of extreme weather any more than a change in a baseball player’s batting average causes home runs.

In weather forecasting, scientists have long recognized that forecasts of the weather — the state of the atmosphere — diverge significantly over 10 days or so into the future based on even very small changes in the initial conditions that are input to the forecasting model.

This divergence is not just a characteristic of forecasts from models, but it is also a characteristic of the real world. When humans alter the earth system — whether through carbon dioxide emissions, particulate air pollution, land surface changes, and myriad other actions — we change the conditions which influence the state of the atmosphere, and thus the future evolution of the state of the atmosphere.5

How much weather is there? In other words, how many atmospheric states are possible? One answer to this question was provided by van den Dool 1994, who asked how long it would take to observe an analogous weather pattern — (like the one in the image above) in the Northern Hemisphere — to one selected at random. His answer:

[I]t would take a library of order 1030 years to find 2 observed flows that match to within current observational error over a large area such as the Northern Hemisphere.

That is 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 years!

Because humans alter the Earth system in ways that influence the state of the atmosphere, the weather that we are experiencing today is different than it would have been had there been no people on the planet. In that sense, the specific weather events that occur are indeed caused6 by a wide range of human activities, but not in any deterministic or predictable sense.7

Studies seeking to perform specific extreme event attribution dance around this reality by ignoring the chaotic nature of the atmosphere. For instance, such research commonly assumes that the state of the atmosphere observed for a specific extreme event would have been identical with and without the historical emission of greenhouse gases. Such studies also, almost universally, ignore all other human influences on the climate system that alter the state of the atmosphere.8

For instance, a recent study of 2019 Hurricane Dorian modeled how the hurricane evolved as it made landfall in North Carolina and compared the modeled real storm to a counterfactual model of Dorian with pre-industrial sea surface temperatures fed into the model. That study concluded:

[A]nthropogenic climate change increased the likelihood of Hurricane Dorian’s extreme 3-hourly rainfall amounts and total accumulated rainfall by 8%–18% and 5%–10%

This conclusion is scientifically incorrect.

Hurricane Dorian would not have occurred in a world without human influences on the climate — perhaps another hurricane would have occurred that day or perhaps no hurricane at all. We can say with absolute certainty that due to human influences on the climate system, the atmospheric state in the Northern Hemisphere in late August, 2019 would have been different than the one that we observed.

The study of Dorian is thus a simple sensitivity analysis of the modeled behavior of an actual storm to prescribed lower sea surface temperatures in the model — which may be scientifically interesting, but it can say nothing about the cause of Dorian or its intensity. To quote a funny commercial — That’s not how this works, that’s not how any of this works.

To use an analogy — such studies are similar to asking what color your eyes would be if your mom had married that good-looking Swedish guy she met in college instead of your actual father. We could ask genetic experts to perform many studies and to develop probabalistic models of eye color outcomes based on you mother’s genes and those of the handsome Swede. But that person wouldn’t be you! The question doesn’t make sense.

The climate community well knows that specific extreme event attribution is not possible. In its 2016 report on event attribution the NASEM explained:

Event attribution questions are often posed in terms of a specific actual event, but definitive attribution of a specific event in a deterministic manner is generally not possible.

This is absolutely correct.

The IPCC’s detection and attribution framework will continue to remain the state of the art for identifying changes in extreme weather events and identifying why those changes have occurred. Efforts to identify the causes of specific extreme weather events will forever remain alchemy.

This post was originally posted on Roger’s Substack, The Honest Broker. If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing here.

1 Just after 3:06 in the video of the event.

2 The 2012 La Jolla workshop was organized by the Union of Concerned Scientists, which had a member on the current NASEM “scientific” study of attribution and whose job at UCS is to advance climate litigation. She was recently replaced on the committee.

3 The notion of causality in law is fascinating and does not neatly align with notions of causality in science — probably worth its own post sometime. For today, a common sense understanding of causality will suffice.

4 The IPCC Glossary does not define weather, a curious oversight.

5 It is an interesting research question as to how large any such human activity must be to alter “initial conditions” such that future atmospheric states evolve differently than they would have in the absence of the perturbation. See Pielke Sr. and colleagues for a related discussion.

6 The relevant concept here is “chaotic causality.”

7 There is a significant literature consistent with the arguments of this post, which is largely ignored in the event attribution literature, for instance: Trenberth et al. 2015, Faranda et al. 2020, Zhang et al. 2021, Seager et al. 2022, Terray and Bador 2025, Ye et al. 2025, Plavcová et al. 2025.