A few days ago the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued a new rule that rescinded the 2009 Endangerment Finding that found that six greenhouse gases emitted from autos posed risks to health and welfare. Also eliminated by the EPA decision are a set of regulations governing emissions from light vehicles and trucks that followed directly from the Endangerment Finding.

You can read background leading up to the ruling — here, here, and here. I’ve spent the past few days reading the rule and associated documents, and have prepared an initial set of questions and answers on arguments in the rule that stood out to me as important.

Online discussion of the rule that I’ve seen suggests hyperbolically that it is either the end of all U.S. climate policy or alternatively the greatest regulatory rollback in U.S. history. I don’t align with either view. While the final rule is much stronger than I anticipated, based on EPA’s early arguments, I still think that it has a good chance of being struck down, but it might be close.

What the rule does offer is an opportunity for Congress — to at least clarify the language of Clean Air Act, but perhaps more significantly to open up a debate over what a common-sense, bipartisan approach to greenhouse gas policy might look like in legislation.

With that, let’s go to the FAQs . . .

What is the “endangerment finding” debate about anyway?

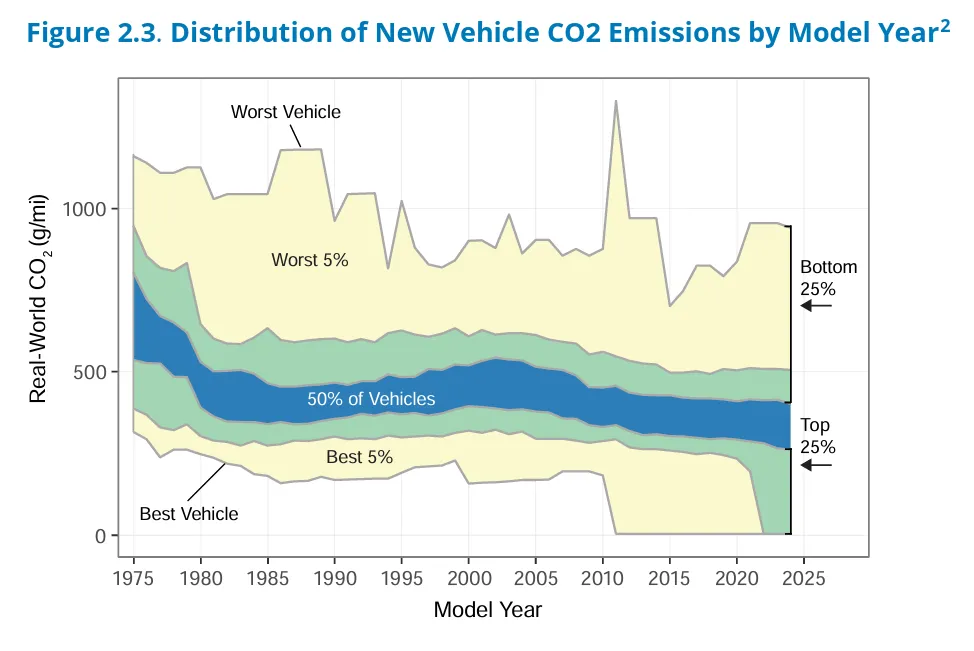

The entire debate over the Endangerment Finding is based on interpretations of the meaning of a 112-word paragraph in the Clean Air Act., shown in full below.

The EPA determines that CAA section 202(a)(1) does not authorize the Agency to prescribe emission standards in response to global climate change concerns for multiple reasons, including the best reading of the statutory terms “air pollution,” “cause,” “contribute,” and “reasonably be anticipated to endanger.” This statutory interpretation is corroborated by application of the major questions doctrine. The EPA further determines that GHG emission standards for new motor vehicles and engines do not impact in any material way the public health and welfare concerns identified in the Administrator’s prior findings in 2009.

EPA argues that legal judgments since the issuance of the 2009 endangerment finding call for a reinterpretation of the language of CAA Section 202(a)(1), and in ways that it argues that are the “best reading” of the intent of Congress when the legislation was enacted.

In particular, EPA relies heavily on the Supreme Court’s 2024 Loper Bright decision that ended Chevron deference to federal agencies. EPA quotes from that decision to argue that:

the scope of an agency’s own power” is determined not by deference to asserted expertise, but by “the best reading of the statute,” which is fixed at the time of enactment. Loper Bright Enters. v. Raimondo, 603 U.S. 369, 400-01 (2024)

My view is that Congressional legislation is often imprecise and imprecision can grow over a half century or more. Loper Bright does ask more of Congress to be both precise and current. In some respects the ambiguities of the Clean Air Act are nothng more than political Rorschach tests — I’ll return to Congress way down below.

What emissions regulations are eliminated by this rule?

EPA lists the following regulations that are eliminated due to its new rule:

Vehicle Greenhouse Gas Rulemakings Affected by this Action. The final rule rescinds EPA GHG emission standards and related regulatory provisions for light-, medium-, and heavy-duty vehicles and engines promulgated pursuant to the 2009 Endangerment Finding, including the following rulemakings:

Light-Duty Vehicle Greenhouse Gas Standards

- Model Year (MY) 2012–2016 Light-Duty Vehicle GHG Standards

- Joint EPA–National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (NHTSA) standards establishing federal GHG emission limits for passenger cars and light trucks.

- MY 2017 and Later Light-Duty Vehicle GHG Standards

- EPA standards tightening GHG emission requirements beyond MY 2016.

- MY 2023–2026 Light-Duty Vehicle GHG Standards

- Revisions to national GHG standards for passenger cars and light trucks beyond MY2022.

- MY 2027 and Later Light-Duty Multi-Pollutant Standards (GHG Provisions)

- Tightening GHG emission requirements beyond MY 2027.

Medium- and Heavy-Duty Vehicle and Engine GHG Standards

- Phase 1 Medium- and Heavy-Duty Vehicle GHG Standards

- Initial federal GHG standards for heavy-duty engines and vehicles.

- Phase 2 Medium- and Heavy-Duty Vehicle and Engine GHG Standards (Through MY 2027)

- Expanded GHG standards covering tractors, vocational vehicles, heavy-duty pickups and vans, and trailers.

- Phase 3 Medium- and Heavy-Duty Vehicle GHG Standards (MY 2027 and Beyond)

- GHG standards applicable to later model years, including early phases extending into the 2030s.

What effect have these regulations listed above had on greenhouse gas emissions?

According to the EPA 2024 Automotive Trends Report, trends in U.S. auto fleet fuel economy and emissions fall into three distinct periods:

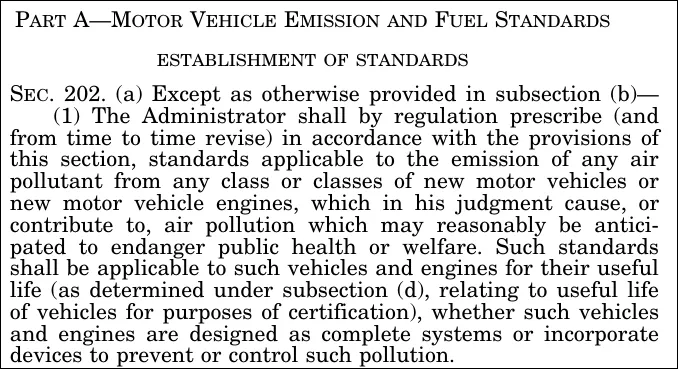

The magnitude of changes in annual CO2 emissions and fuel economy tend to be small relative to longer, multi-year trends. Figure 2.2 [above] shows fleetwide estimated real-world CO2 emissions and fuel economy for model years 1975–2023. Over this timeframe there have been three basic phases: 1) a rapid improvement of CO2 emissions and fuel economy between 1975 and 1987, 2) a period of slowly increasing CO2 emissions and decreasing fuel economy through 2004, and 3) decreasing CO2 emissions and increasing fuel economy through the current model year.

You can see in the figure above that the most recent of those three periods began well before the Endangerment Finding was published in 2009, and has followed a more-or-less linear improvement since about 2004. (Note that there is a suggestion of an inflection point in about 2022, but just 2 years of data.)

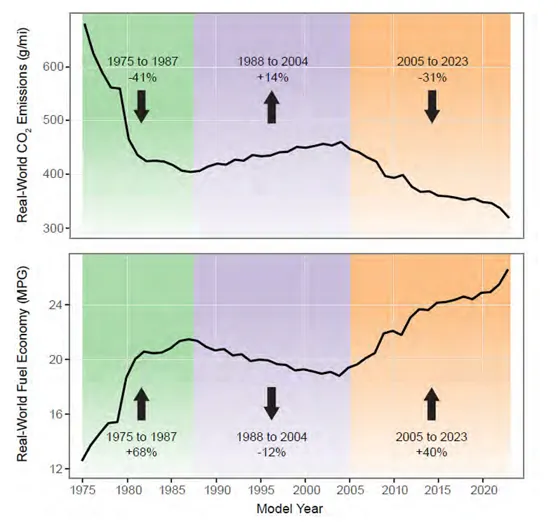

The figure below shows the distribution of CO2 emissions across new vehicles by model year. There is a slow but steady improvement over the past 50 years, and the emergence of EVs is obvious. However, there are few signs of a major step change in the fat part of the curve (i.e., middle 50%).

There are valid arguments to have about the technological chicken and the regulatory egg. There is little doubt that federal regulations since the 1970s have contributed to increased fuel economy, including those implemented following issuance of the endangerment finding — see for instance Knittell 2011, Kiler and Lynn 2015, Allcott and Wozny 2012.

One thing we can be certain of, whatever carbon dioxide emissions reductions have resulted from these regulations, they are tiny in a global context and consistent with the longer-term record of improvements in fuel economy under CAFE standards.

Wait, isn’t this issue about climate science?

That’s what the New York Times and other climate advocates (including the American Geophysical Union and American Meteorological Society) would like us to believe.

Here is the NYT a few days ago:

By scrapping the finding, the Trump administration is essentially disputing the overwhelming scientific consensus on climate change. The vast majority of scientists say the Earth is rapidly and dangerously warming, which is fueling more powerful storms, killing coral reefs, melting glaciers and causing countless other destructive impacts.

Well, no.

EPA is very clear that its decision to rescind the Endangerment Finding and associated regulations is based entirely on legal arguments and not any novel scientific claims about climate.

EPA abandoned its earlier suggestion that it would rely on an “alternative rationale” from the Department of Energy’s Climate Working Group (CWG):

As the EPA does not adopt or rely on the proposed scientific alternative rationale in this final action, the Agency does not need to, and is not legally required to, summarize or respond to comments that address that unfinalized alternative as we consider those comments to be out of scope of this rulemaking. Therefore, comments related to climate science are out of scope of this rulemaking. This includes, but is not limited to, comments on the Department of Energy’s (DOE) Climate Working Group (CWG). [emphasis added]

This was a smart decision by EPA, as I’ve explained here at THB.

However, we should continue to expect climate advocates in the science community to continue to assert loudly that their scientific authority trumps the law and democracy, and thus dictates policy. The EPA’s actions may well not survive legal review, but that won’t be because of arguments about climate science or appeals to scientific authority.

Does EPA call climate change a hoax?

Actually no. EPA sticks to its legal arguments in its response to comments:

While commenters may or may not identify a global problem to be addressed, that does not mean Congress gave authority to the EPA in CAA section 202(a)(1).

What is the core of EPA’s legal argument?

I’m no lawyer, of course, but as a policy guy, here is how I’d boil down the EPA argument:

- EPA argues that GHGs must satisfy the same legal standards for regulation as other types of pollutants.

Put simply, regardless whether GHGs are “air pollutants” as defined in CAA section 302(g), they must satisfy the same standard as any other emitted “air pollutant” by causing or contributing to “air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare.

EPA argues that the regulation of automobile emissions is not allowed under the Clean Air Act because the harm from those emissions is far too small to endanger public health or welfare. They run some numbers:

[R]etaining a GHG emission standards program for vehicles and engines would result in a 0.007 (0.005-0.009) °C impact on projected GMST [Global Mean Surface temperature] through 2050 and 0.019 (0.012-0.027) °C impact on projected GMST through 2100. Retention would result in a 0.05 (0.03-0.053) cm impact on projected GSLR [Global Sea Level Rise] from 2027 to 2050 and 0.7 (0.20-2.39) cm impact on projected GSLR from 2027 to 2100.

EPA further argues that changes in temperatures and sea levels are not indicators of actual impacts.

[T]he projected impacts on GMST and GSLR are not themselves the adverse impacts on health and welfare relevant for purposes of the analysis. Rather, they are imperfect proxies for such adverse impacts

EPA emphasizes that the focus of regulation is not simply “air pollution” but “air pollution that can be reasonably anticipated to endanger health or welfare.”

[W]e conclude that CAA section 202(a)(1) requires that emission standards be capable of having a material impact on the identified danger for the Administrator to conclude that the emissions “contribute” to air pollution that may “reasonably be anticipated” to endanger public health and welfare. If controlling or eliminating the emissions would not materially impact the identified danger, the emissions do not “contribute” to the air pollution. And because the emitted “air pollutant” and the “air pollution” are defined in this context as the “six well-mixed GHGs,” the air pollution cannot “reasonably be anticipated” as endangering health or welfare in the CAA section 202(a) context if controlling or eliminating all vehicle and engine emissions would have no impact. Put another way, the inability of GHG emission standards to have any material impact demonstrates that GHG emissions from new vehicles and engines do not contribute to air pollution that endangers public health or welfare.

EPA further argues that the imposiibility of identifying benefits of the regulations, given the tiny effect on emissions and indirect path to impacts, means that “immense costs” are not allowed under the Clean Air Act.

Even if the CAA section 202(a)(1) authorized the Endangerment Finding as a standalone decision, it would be unreasonable and impermissible to retain a regulatory program that imposes immense costs while providing no material value in furtherance of a legitimate statutory objective. This alternative basis turns on the statutory language in CAA section 202(a) more generally, including the cost consideration requirements of CAA section 202(a)(2). As the Supreme Court explained in Michigan, agencies are bound to consider cost unless the statute expressly provides otherwise. Here, where the costs or regulation are certain and immense but the health and welfare value of regulation are uncertain and de minimis, it is unreasonable to maintain the GHG emissions program.

Each of these arguments is contestable as a matter of law — Another Rohrschach test. I’d much prefer that Congress resolve these issues rather than the courts, simply as a matter of good democratic practice.

Along those lines, will the EPA rule survive judicial review?

Who knows?

Cass Sunstein, who I have a lot of respect for, thinks that it will not survive, arguing, “the rescission seems more likely than not to be struck down. It is a close analogue to the Biden administration’s school loan forgiveness program, struck down by the Supreme Court.”

In fairness, Sunstein offered his views before fully taking in the final rule. Upon reading the rule, I am not convinced it would be struck down, particularly by this Supreme Court. That said, there would seem to be plenty of legal room for the Endangerment Finding to be upheld and EPA also given the latitute to revise regulations in a deregulatry direction (the social cost of carbon in Biden-era cost-benefit analyses would seen to offer a big opportunity, but I digress).

How can this mess be fixed?

Easily. Hello, Congress.

The EPA explains:

The appropriate policy response to global climate change concerns is a decision vested in Congress, and Congress did not decide the Nation’s policy response to these concerns when it enacted CAA section 202(a)(1) to address domestic air pollution problems nearly sixty years ago, or in any subsequent amendment thereto.

Setting aside the big issue of the Nation’s policy response to climate change, Congress has an opportunity to resolve the ambiguities of the 112 words of the Clean Air Act’s Section 202(a)(1) rather than leaving that to the Executive and Judicial branches. In fact, that is Congress’ job!

For Republicans, clarifying that the role of GHGs under the Clean Air Act would offer greater guidance to EPA and other regulatory agencies, and require that imposed costs result in tangible benefits to the nation. It would also eliminate the possibility of the Endangerment Finding rising from the dead on January 20, 2029.

For Democrats, opening up discussion of the CAA might offer a path forward on more comprehensive energy policies focued on affordability, competitiveness, and also decarbonization. If climate advocates are fighting over the EPA Endangerment Finding, then they have already lost.

In the big picture the Endangerment Finding and assocaited regulations are immaterial to global emissions and climate change. It is nonetheless an important issue where the future of important policies related to climate, innovation, energy, and affordability are being debated.