26 years ago, Virginia Postrel published The Future and Its Enemies, which I still consider one of the most insightful books of our time. The book’s subtitle, The Growing Conflict Over Creativity, Enterprise, and Progress, has become even more relevant since 1998.

Virginia gave a presentation on the ideas in her book at the Progress Conference in Berkeley last weekend, which I attended and spoke at. Sponsored by the Roots of Progress Institute and other co-sponsors, this gathering was everything I had hoped for—interesting, thoughtful presentations and discussions with curious people interested in ideas and their consequences for humanity. The mix of formal presentations and spontaneous conversations was enlivening, aided by the ease and comfort of the different spaces at Lighthaven.

The broad theme of The Future and Its Enemies is that people can have two general dispositions about the future: stasis and dynamism:

How we feel about the evolving future tells us who we are as individuals and as a civilization: Do we search for stasis—a regulated, engineered world? Or do we embrace dynamism—a world of constant creation, discovery, and competition? Do we value stability and control, or evolution and learning? … Do we think that progress requires a central blueprint, or do we see it as a decentralized, evolutionary process? … These two poles, stasis and dynamism, increasingly define our political, intellectual, and cultural landscape. (Postrel 1998, p. xiv)

The book presents a compelling argument about the dynamic nature of progress and innovation, contrasting these two fundamental mindsets. Even before developing the theme, Postrel’s observation has a profound kind of “now that I’ve seen it I can’t unsee it” essence.

Stasis

Stasists, who prefer control, predictability, and central planning, resist change due to their desire for order and fear of uncertainty. Stasis is a widespread disposition toward stability and certainty, which evolutionary psychology would suggest is deeply grounded in human nature.

On one stasist extreme, reactionaries value the past more than either the present or the unknown future, and they want a return to the idyllic past. Such romanticism pre-dates Jean-Jacques Rousseau, but his work inspired deep objections to urbanization and industrialization in the early 19th century, objections that persist and retain their Rousseauian traits to this day. In an odd twist of strange intellectual bedfellows, today’s new right nationalist and Catholic integralist movements are compatible with Rousseau’s invocation to reject cosmopolitanism, innovation, and progress in favor of this romanticized, fictional, Utopian past.

On the other extreme, stasis shows up as a desire for control. Stasists seek predictability, order, and control over complex systems—especially in the face of uncertainty brought by innovation and technological progress.

When thinking about economic growth, stasis does not mean a zero growth rate, but rather a known, predictable process of change leading to growth. That desire breeds a desire for control of technological, economic, and social systems to make the process of change predictable. It manifests as technocracy: decisions about social, economic, and technological issues are made by experts rather than left to the decentralized, adaptive processes of markets and individuals.

In Postrel’s context, technocracy emerges as a stasist solution to the uncertainty and perceived chaos of dynamism. Stasists believe that by entrusting authority to technical experts—whether they be scientists, engineers, economists, or bureaucrats—society can better predict and manage outcomes, ensuring safety, fairness, and order. The technocratic approach assumes that with the right data and expertise, a centralized authority can optimize decisions for the greater good.

The Party of Life

In contrast, dynamists embrace the open-ended nature of progress, supporting experimentation, adaptation, and decentralized decision-making. Dynamism mirrors evolutionary processes in nature, where change is constant and progress emerges through decentralized, adaptive responses to the environment. This dynamic process, much like evolution itself, cannot be controlled or predicted centrally. There is no telos, no known, shared outcome toward which evolutionary processes drive.

Postrel’s emphasis on decentralized evolutionary processes uses Hayek’s concept of dispersed knowledge: knowledge is diffused across individuals and no single authority can possess or process all of the information necessary to manage complex systems.

Hayek argued that decentralized decision-making is more effective because individuals on the ground—those with direct experience—are best positioned to respond to local conditions and adapt accordingly. Postrel builds on this idea by suggesting that dynamism thrives in systems where authority is similarly dispersed, allowing for experimentation, trial and error, and the organic emergence of solutions, much like evolutionary processes.

Chapter 2 of The Future and Its Enemies is titled “The Party of Life”, evoking the open-ended evolutionary processes that characterize dynamism. It also suggests a curiosity, an openness to new ideas, that is an essential input to and a fundamental aspect of progress.

Technological Invention and Innovation

Postrel’s argument about dynamism, evolutionary processes, and dispersed knowledge has direct relevance to technological change. She suggests that technological progress, much like biological evolution, is unpredictable and emerges through decentralized innovation rather than central planning, mirroring Hayek’s insight that no single entity can have enough knowledge to foresee or control all the variables involved in invention and innovation.

Dynamism enables a continuous process of experimentation and adaptation. New technologies often arise from individual initiatives, start-ups, and iterative trial-and-error processes in various contexts, rather than from top-down hierarchies. Because knowledge about consumer needs, resource availability, and technological potential is dispersed across society, technological progress is most effective when decision-making is equally decentralized, allowing for more flexible, diverse, and context-specific solutions to emerge.

Dynamism and Progress

A dynamist mindset is an essential catalyst for progress. Postrel’s dynamism reflects an open-ended, evolutionary approach where innovation emerges from the bottom up through the contributions of individuals operating within a system of dispersed knowledge and authority. Progress is not the product of centralized control, but of decentralized adaptability and innovation.

A dynamic approach embraces uncertainty and fosters marketplaces where technologies can evolve, compete, and improve through feedback from users and developers. Postrel’s framework suggests that just as evolutionary processes depend on variation and selection, technological progress relies on a similarly open-ended environment, where the best ideas and innovations are allowed to flourish through decentralized experimentation and adaptation.

Stasis Hinders Progress

This perspective also suggests that attempts to control or slow technological change through regulation or centralized authority tend to stifle innovation. The economic historian Deirdre McCloskey frames this dynamism as equality of permission, permission to experiment, to tinker, to try new things, to “have a go” as she often says:

It should be simply an equality of permission, or allowance, or approval of a general right to do, to enter in the race as an adult, what Adam Smith proposed in 1776 as “the obvious and simple system of natural liberty.” Wherever you start in the race, or wherever the betting might predict you will end it, under a liberal equality of permission you may, as the sporting British put it, “have a go.” (McCloskey 2024, p. 9)

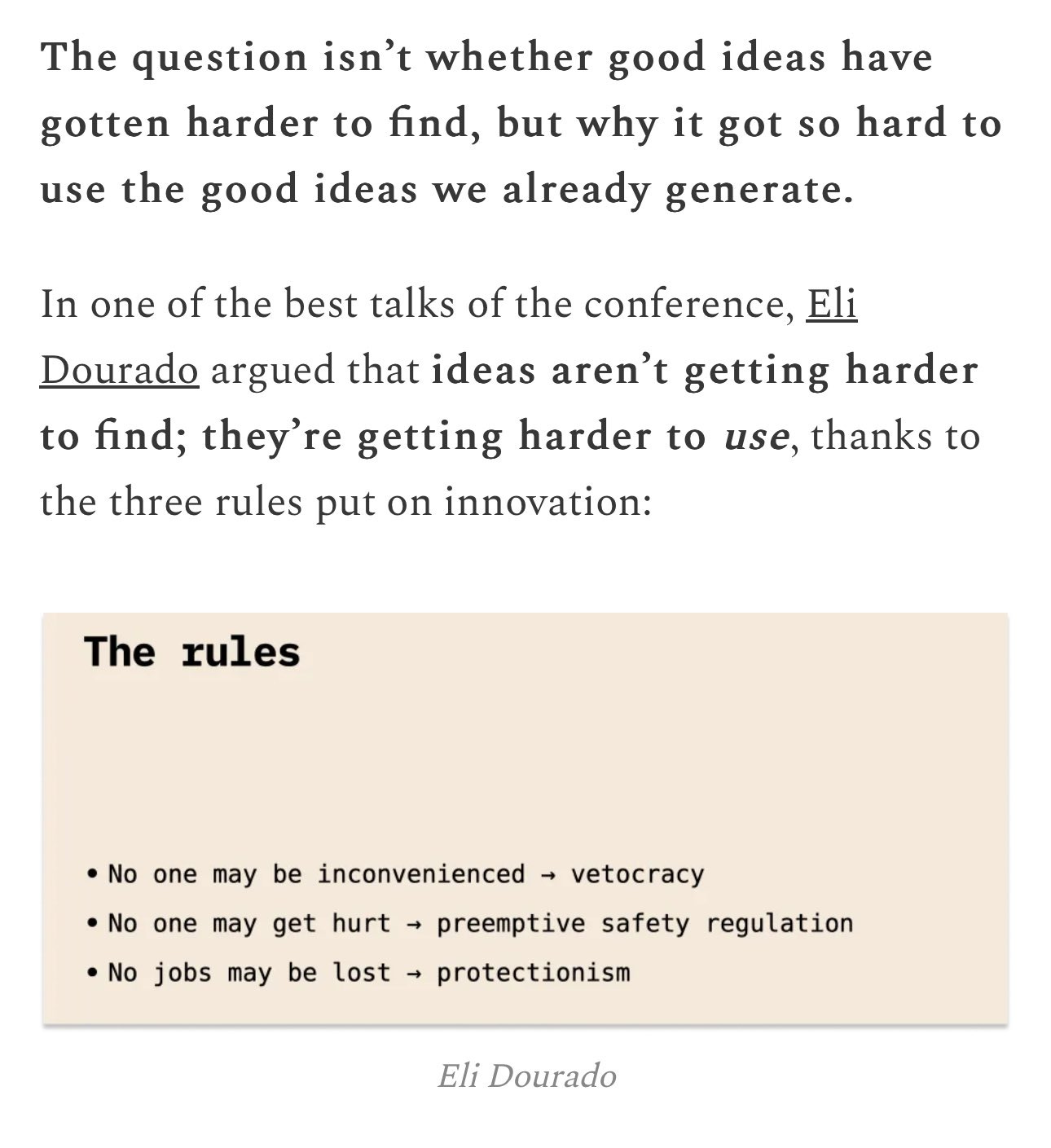

Regulation and centralized authority as a drag on progress also relate to another theme of the Progress Conference: are ideas getting harder to find? Packy McCormick has a really great essay from the conference on that question (and one of my highlights of the weekend was meeting him), What Do You Do With an Idea? He highlighted the argument that ideas themselves are not scarce, but that many past innovations remain untapped due to regulatory, economic, and cultural barriers. In this claim he draws on another great talk from the conference, from Eli Dorado of the Abundance Institute (disclosure: I am a Fellow at the Abundance Institute and a big Eli stan from way back when he was a graduate student): ideas are harder to use because of overly-precautionary formal and informal rules:

Source: What Do You Do With an Idea?

Overly prescriptive rules are barriers to building, innovation, and experimentation using the ideas we have, which also stifles our generation of new ideas. We can’t use ideas because we have moved so far away from McCloskey’s equality of permission. Using ideas and creating new ones requiers reducing regulatory hurdles and creating an environment where both old and new ideas can be built and scaled into meaningful, substantive innovations. [Note: I have more to say about Packy’s essay that I will save for the future.]

Equality of permission enables ideas to beget more ideas. Dynamism as a mindset and equality of permission as an institutional stance are pillars of progress.

This article was originally published on Lynne’s Substack, Knowledge Problem. If you enjoyed this piece, please consider subscribing here.