On Friday June 28, the Supreme Court issued their 6-3 ruling in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, overturning the deference to administrative agencies established in the Chevron v. Environmental Protection Agency ruling in 1984. So far opinions vary on how big a change this will ultimately be (courts have not been relying much on Chevron deference in the past 8 years) and whether the change will be beneficial or costly.

With the caveat that I am not a lawyer but am a regulatory economist, this ruling realigns the division of labor between courts and Congress to make that division of labor more consistent with the separation of powers delineated in the Constitution. The political theory of beneficial separation of powers and the economic theory of beneficial specialization and division of labor coincide to align incentives and promote accountability to voters. Here I’m going to make economic arguments supporting that claim grounded in a game-theoretic model. For an excellent legal analysis that I find extremely persuasive I recommend Case Western Law School’s Jonathan Adler on the ruling:

Going forward, courts will continue to uphold reasonable agency interpretations of regulatory statutes, particularly when the subject matter is technical or complex, and agencies will still exercise broad swaths of policy discretion, as the Loper Bright opinion expressly contemplates. Yet agencies will have to spend more time considering and showing how their desired approach to a given statute best conforms to the relevant text and will be less able to alter or reverse long-standing statutory interpretations without going back to Congress. Where statutes have been on the books for decades without meaningful amendment or revision, this will make it more difficult for agencies to adjust to changing circumstances. The big question will thus be whether Congress gets the message and responds with more frequent legislating (something about which Chris Walker and I have some thoughts).

The core of the Loper Bright ruling on Chevron deference hinges on the role of the Administrative Procedure Act. The Administrative Procedure Act (APA) of 1946 is a key piece of legislation in U.S. administrative law that establishes the framework for how federal administrative agencies propose and establish regulations (and most states have adopted versions of it). It was designed to ensure fairness, transparency, and public participation in the rulemaking process, as well as to provide a means for judicial review of agency actions.

Two of the APA’s most important provisions are notice-and-comment rulemaking and procedures for judicial review. Agencies must publish a notice of proposed rulemaking in the Federal Register and provide the public with an opportunity to comment on the proposed rule, usually through written submissions. After considering the public comments, agencies must publish the final rule in the Federal Register, along with a statement of the basis and purpose of the rule. The APA also provides for judicial review of agency actions, ensuring that they are not arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with the law. Courts can review both procedural and substantive aspects of agency decisions, including reviewing the agency’s compliance with statutory requirements and whether the agency has adequately explained its decision.

There’s an extremely useful literature in institutional political economy on administrative procedure. The core of this literature, called McNollGast as a neologism of the three co-authors’ names, examines the incentive effects of the use of procedural requirements as political control. The seminal paper, “Administrative Procedures as Instruments of Political Control” (McCubbins, Noll, and Weingast, JLEO 1987) explores the question of the delegation of policy-making authority to bureaucratic agencies and the mechanisms available to elected officials to control and monitor these agencies to ensure compliance with their policy goals.

They model legislative delegation to agencies as a principal-agent problem inherent in the relationship between elected officials (principals) and bureaucratic agencies (agents). The principal-agent problem arises because bureaucrats, who possess specialized knowledge and are not subject to direct electoral control, may pursue their own interests rather than those of the elected officials. This divergence of interests creates a need for mechanisms to align the actions of bureaucrats with the policy preferences of elected officials.

Administrative procedures are an institutional way to foster that alignment because they are designed to structure the decision-making environment within agencies, thereby limiting the range of feasible policy actions and ensuring that agencies remain responsive to the interests of elected officials and their constituents. Procedures such as notice-and-comment rulemaking, public participation requirements, and judicial review standards are used to mitigate information asymmetries and enfranchise important political constituencies in the decision-making process. These procedures enable elected officials to ensure that their policy preferences are carried out without requiring constant monitoring and intervention, thereby providing a cost-effective solution to the principal-agent problem in democratic governance.

In the Loper Bright ruling, the Court decided that agency interpretations of statutes are not entitled to deference in situations where the agency interpretation of law differs from the statutory interpretation on which a court would otherwise rule. The Court emphasized that under the Administrative Procedure Act, it is the responsibility of the courts to interpret the law, not the agencies, and that ambiguity itself is not delegation.

Chevron’s presumption is misguided because agencies have no special competence in resolving statutory ambiguities. Courts do. The Framers anticipated that courts would often confront statutory ambiguities and expected that courts would resolve them by exercising independent legal judgment. Chevron gravely erred in concluding that the inquiry is fundamentally different just because an administrative interpretation is in play. The very point of the traditional tools of statutory construction is to resolve statutory ambiguities. That is no less true when the ambiguity is about the scope of an agency’s own power—perhaps the occasion on which abdication in favor of the agency is least appropriate. (Loper Bright v. Raimondo 2024, p. 5)

The APA thus codifies for agency cases the unremarkable, yet elemental proposition reflected by judicial practice dating back to Marbury: that courts decide legal questions by applying their own judgment. It specifies that courts, not agencies, will decide “all relevant questions of law” arising on review of agency action, §706 (emphasis added)—even those involving ambiguous laws—and set aside any such action inconsistent with the law as they interpret it. And it prescribes no deferential standard for courts to employ in answering those legal questions. That omission is telling, because Section 706 does mandate that judicial review of agency policymaking and factfinding be deferential. See §706(2)(A) (agency action to be set aside if “arbitrary, capricious, [or] an abuse of discretion”); §706(2)(E) (agency factfinding in formal proceedings to be set aside if “unsupported by substantial evidence”). (Loper Bright v. Raimondo 2024, p. 22)

The majority opinion highlighted that statutory ambiguities should not be seen as implicit delegations of law-interpreting power to agencies. Instead, courts are equipped and expected to resolve these ambiguities using traditional tools of statutory construction, which do not amount to policymaking.

Finally, the view that interpretation of ambiguous statutory provisions amounts to policymaking suited for political actors rather than courts is especially mistaken because it rests on a profound misconception of the judicial role. Resolution of statutory ambiguities involves legal interpretation, and that task does not suddenly become policymaking just because a court has an “agency to fall back on.” Kisor, 588 U. S., at 575. Courts interpret statutes, no matter the context, based on the traditional tools of statutory construction, not individual policy preferences. To stay out of discretionary policymaking left to the political branches, judges need only fulfill their obligations under the APA to independently identify and respect such delegations of authority, police the outer statutory boundaries of those delegations, and ensure that agencies exercise their discretion consistent with the APA. By forcing courts to instead pretend that ambiguities are necessarily delegations, Chevron prevents judges from judging. (Loper Bright v. Raimondo 2024, pp. 6-7)

The dissent, written by Justice Kagan, argued that the majority’s decision overturns a well-established precedent that has been relied upon for decades. The dissent emphasized the importance of Chevron in ensuring that agencies, with their expertise and policy-making roles, have the authority to interpret ambiguous statutes. This deference is based on the presumption that Congress intends for agencies to fill in the gaps of regulatory schemes.

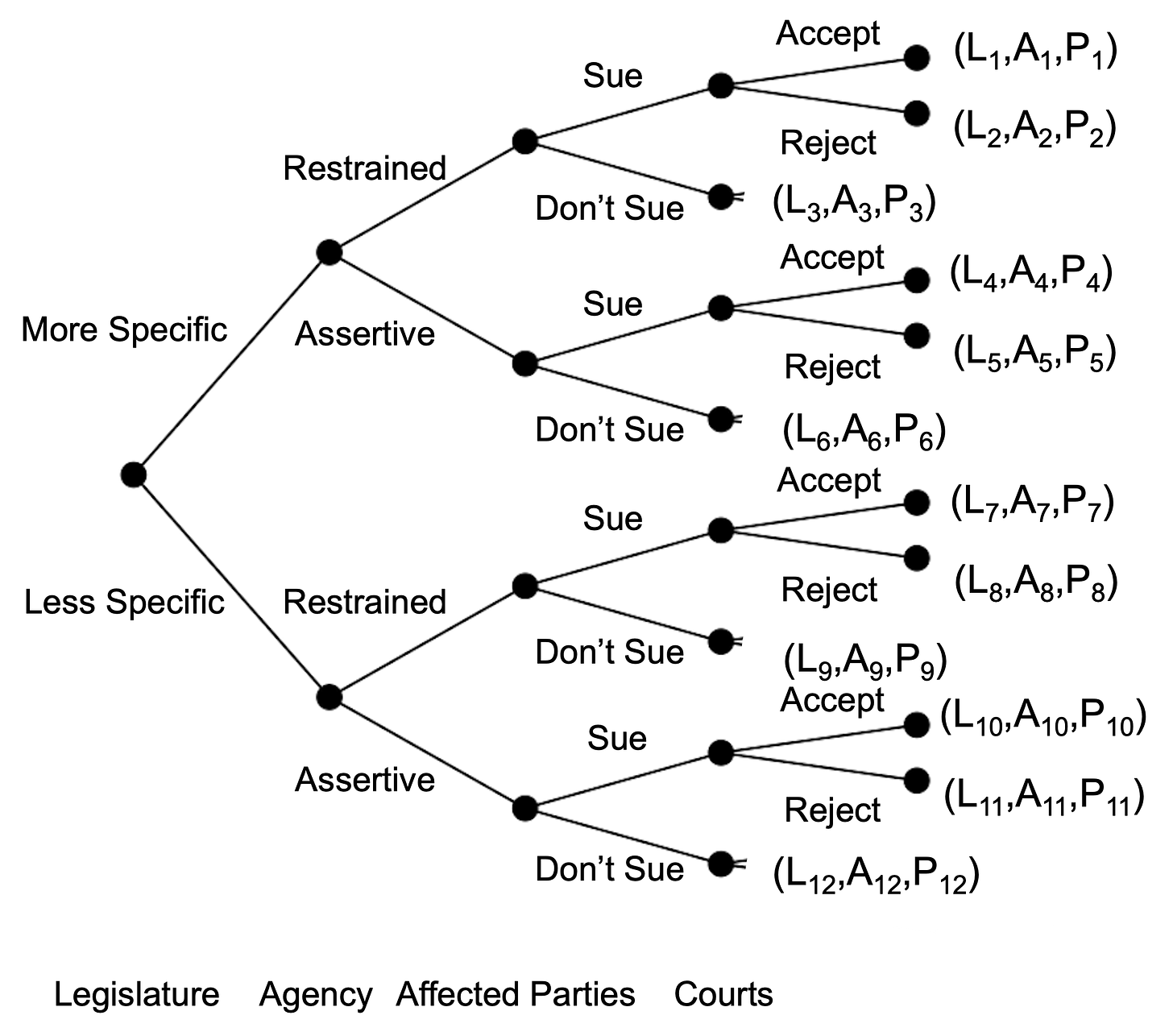

I want to apply a game theoretic analysis that models the strategies and payoffs to the various parties in the situation to examine whether this ruling make the regulatory process incentive compatible in the way McNollGast laid out in their principal-agent framing of the problem. The model I’ve constructed here is an intertemporal, sequential, extensive form game with four players (and with their strategies in parentheses):

- Legislature (more specific, less specific)

- Administrative agency (assertive interpretation, restrained interpretation)

- Affected party (sue, don’t sue)

- Court (accept agency interpretation, reject agency interpretation)

The course of action is that the legislature writes a statute with some delegation to an administrative agency, the agency formulates regulations (within the APA procedures), an affected party can choose to sue the agency, and a court hearing the lawsuit chooses to accept the agency’s statutory interpretation or not. Taking into account the outcomes without a lawsuit there are 12 possible outcomes, with payoff vectors for the three players in each outcome(L_i, A_j, P_k).

Some simplifying assumptions: One important one is that I am interpreting the agency payoff as the value to the agency of their perception of their work, NOT as the value (benefit-cost) of the regulation they implement; that assumption may or may not make a huge difference and it would be an empirical question that varies by agency. I’m going to assume that the affected parties are reactive and do not have any strategy other than to respond to regulations with lawsuits. This means I am abstracting from an important part of the process: the notice and comment period at the core of the APA, which provides a forum for criticism and an opportunity for the agency to modify its rules to incorporate the comments it is required to consider. It also means I am abstracting from the public choice analysis of affected parties lobbying to influence legislation and its interpretation. I’m also assuming away the purported “chaotic transition with lots of lawsuits” because the ruling explicitly stated that existing regulations will be grandfathered in to the Chevron deference paradigm. Finally, I am going to talk in terms of illustrative cases and will not assign probabilities to any particular outcome, which limits what I can say but can be changed if you want to be more detailed in your thinking through these cases.

That means the model structure is:

This structure allows us to identify the pathway that has opened Chevron deference to criticism as well as the pathway that is consistent with the ruling. The way you approach a sequential game-theoretic model is to solve backwards. Here I am not going to assign probablilities and generate a full closed-form solution, but will rather use the game-theoretic logic to illustrate how the Loper Bright ruling could change incentives and outcomes.

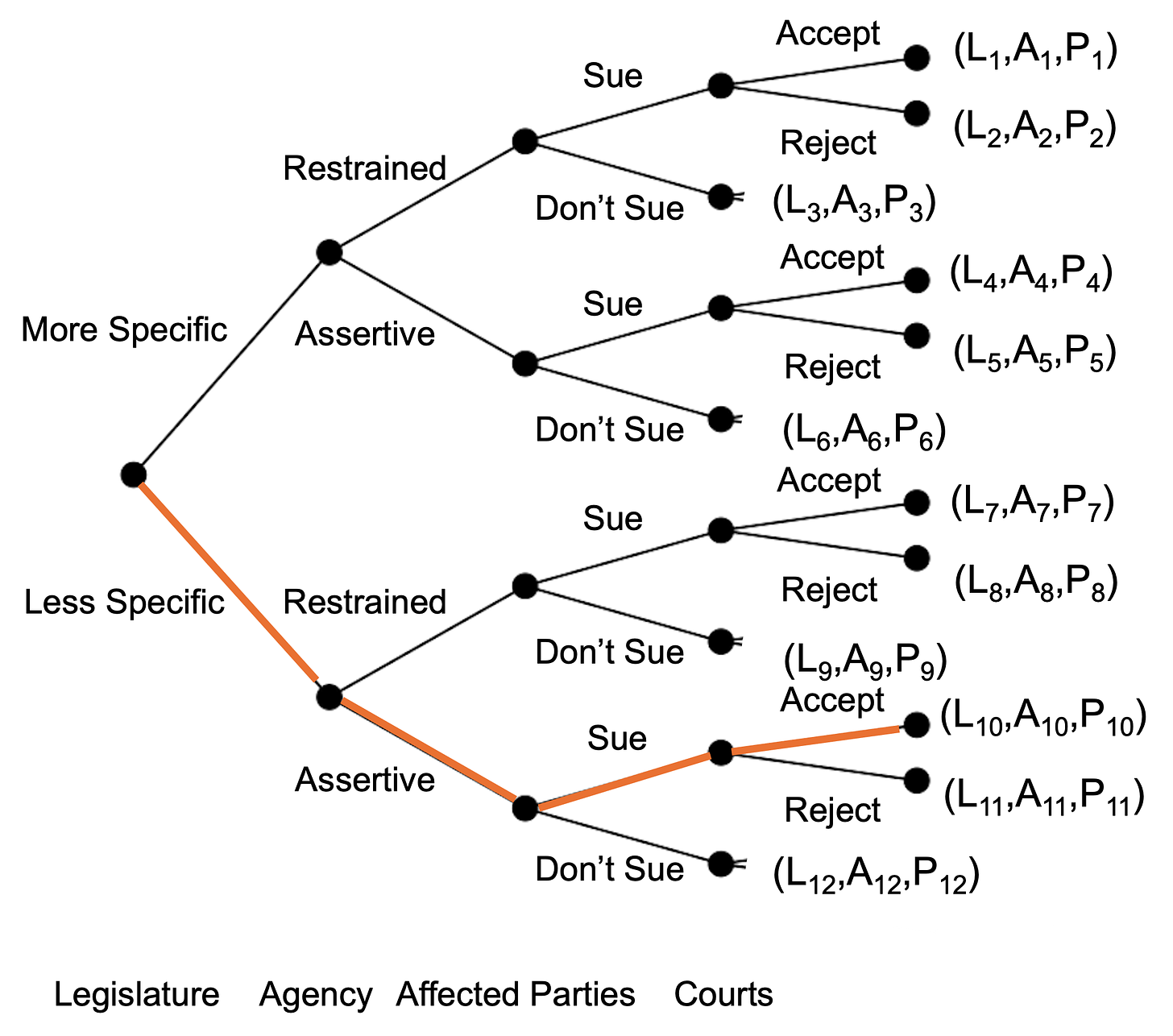

This case illustrates the Chevron deference outcome in the orange path, in which courts are constrained to accept agency interpretation in cases where they would otherwise reject it, leading to payoff vector 10. At the margin that constraint gives agencies an incentive to be more assertive and less restrained in interpreting the statute to implement their mission more broadly. Solving backwards, think about how Congress has written law in the past several years — single-party-driven omnibus bills rather than specific, targeted legislation focusing on single issues and arising out of a process of bargaining, negotiation, and amendment. In that context and with an incentive to avoid difficult votes that might affect their reelection, the legislature in this model has an incentive to write regulatory statutes that are less specific (in other words, L_10 has been greater than L_1 through L_6, and A_10 is also higher because they have expanded scope).

You can also use this game structure to focus your thinking and reach different conclusions from mine about the course of lawmaking and delegation over the past 40 years. I think the orange path is the most realistic representation of Chevron deference’s consequences and incentives to the participants.

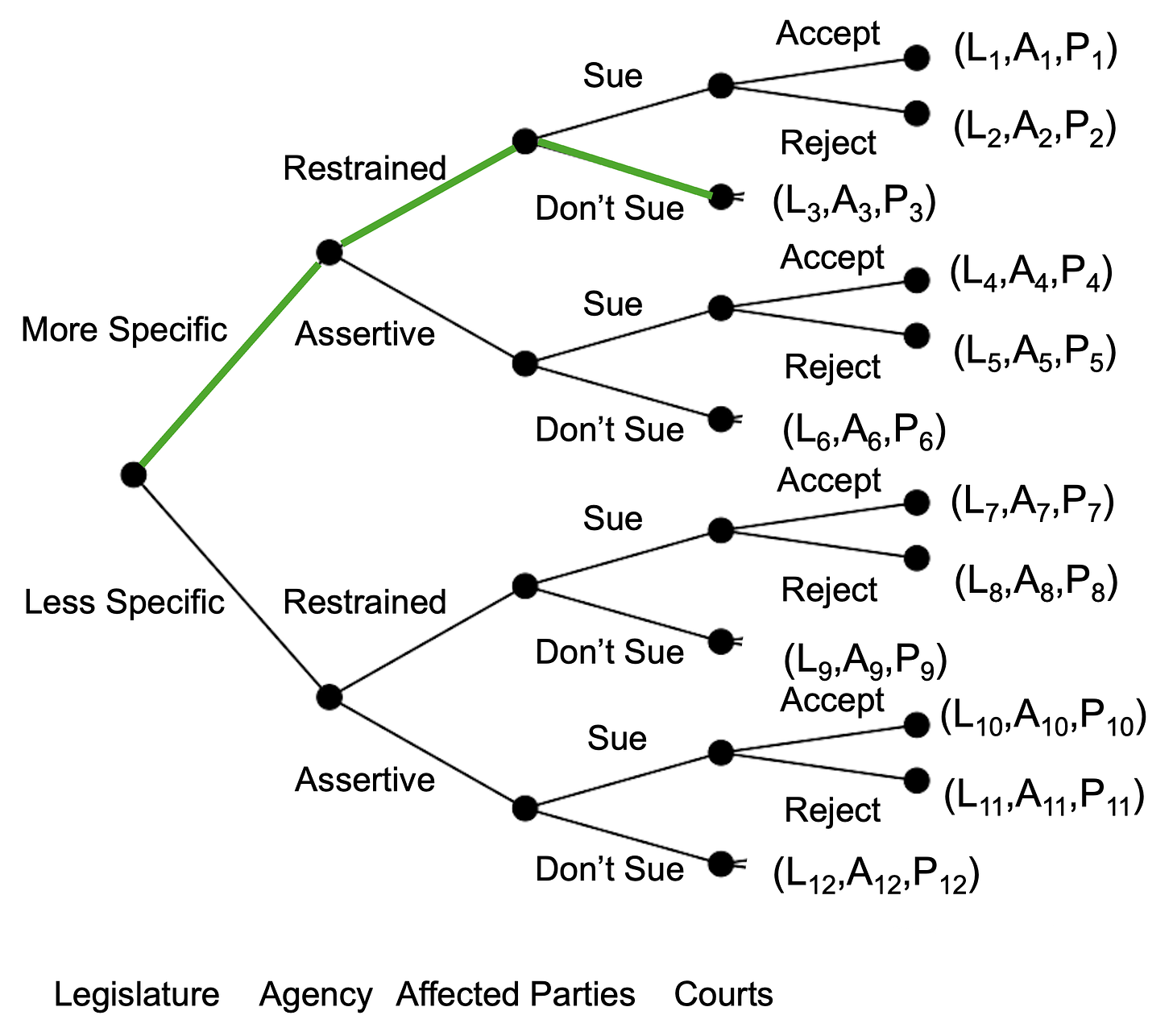

This analysis also highlights some pathways for more robust and sustainable administration that can represent the Court’s argument. In particular, solving backwards, it changes the incentives of Congress and of agencies for what they write, how they delegate, the scope of the regulation and its enforcement. Below the green path indicates my understanding of the best case scenario that the Court envisions with the Loper Bright ruling (and again you can apply this logic differently if you disagree with mine):

In this outcome, Congress faces incentives to write more specific legislation in view of its subsequent judicial interpretation. They write more specific legislation, which agencies implement in a restrained way that the affected parties find generally acceptable and don’t sue. In the payoff structure, this would mean that overall payoff vector 3 is greater than payoff vector 10. One illustrative case for this outcome could be that the productivity benefits to the affected parties is greater than the value of the change to the legislator’s election prospects plus the lost additional regulatory activity. Given the way I’ve set this up I’d probably say that if this outcome meets their expectations then (P_3 – P_10) > (L_3 – L_10) + (A_3 – A_10). It’s also possible that the growth in lawmaking leadership in Congress increases their electability, but I’m no political scientist so I’m not going there.

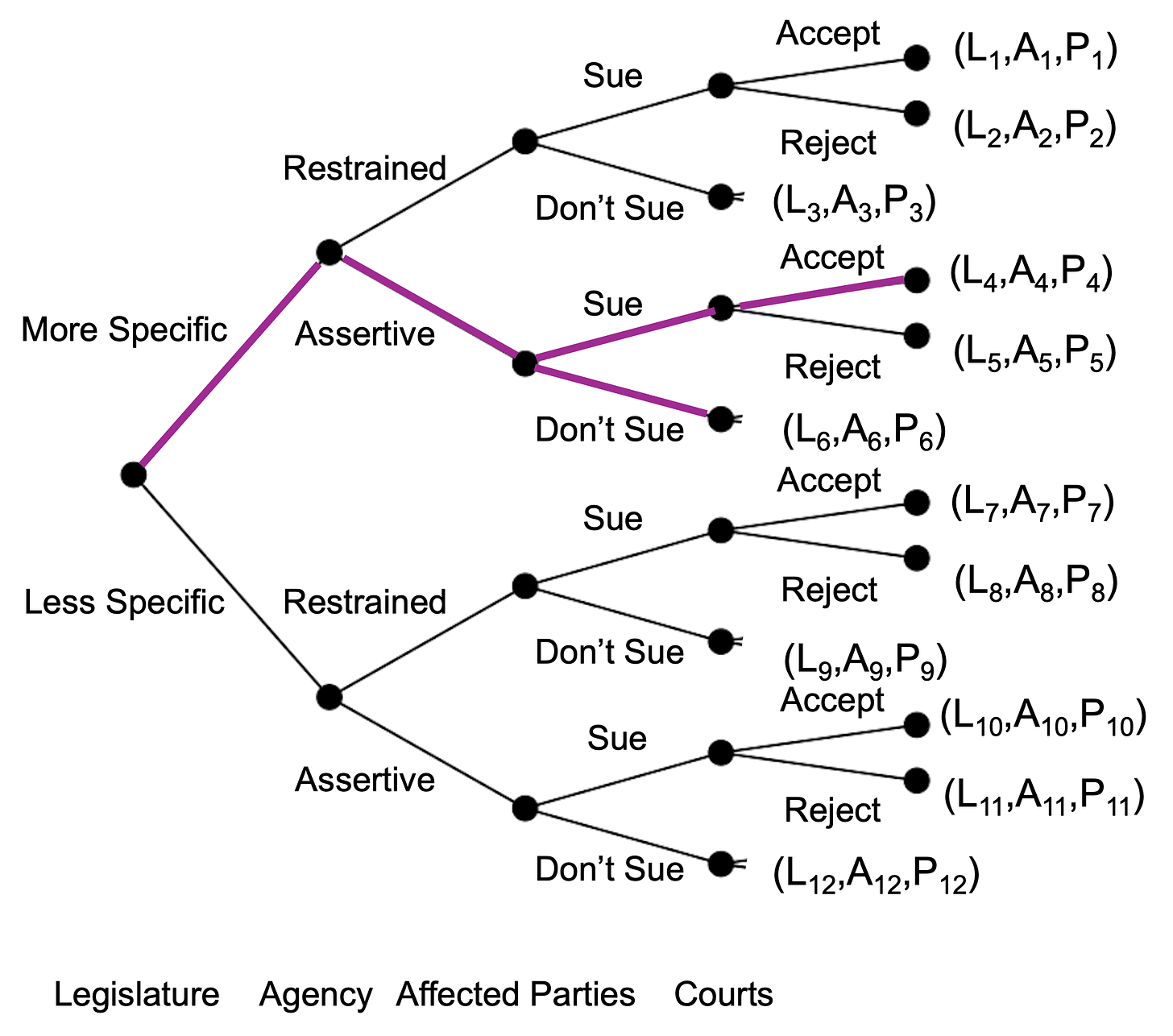

How about the case where an agency interprets the statute assertively and writes/enforces regulations accordingly? The case I have in mind is in purple below:

I understand the Court’s logic as implying that if the legislature writes statute with a view toward its ultimate court interpretation using the APA’s judicial review procedures, it would still have an incentive to write more specific regulatory legislation (in game theory language, they would like to see writing more specific statute as a dominant strategy). Given that, then the agency would choose to implement a more assertive regulation if it sees the (expected) payoffs on that branch (A_4,A_5,A_6) as greater than (A_1,A_2,A_3) (again you can do this with probabilities assigned to each outcome to be more specific). I think this purple path of outcomes is more likely than the green path.

What this game theoretic model does is help us structure our understanding of the Court’s ruling and the values they probably attach to different outcomes, past and future. Statutory interpretation will always be necessary since ex ante statute creation cannot anticipate all possible situations (this is analogous to the observation from organizational economics that we cannot ever write complete contracts, so renegotiation is unavoidable and should be accounted for ex ante). Courts do not have specialized technical expertise, and if Congress performs its rulemaking tasks well by consulting technical experts in the rulemaking process and delegating their regulatory powers more expressly to agencies, then courts can and should focus on statutory interpretation.

Separation of powers meets specialization and division of labor.

What’s required for Congress to write “better” statute? Consultation with experts during the legislative process. Collaboration with legislative colleagues from different parties and with different viewpoints on the subject. Adjudicating constructive disagreement in a pluralist setting. Passing bipartisan legislation on a stand-alone basis and not as part of an omnibus bill that incentivizes vagueness. Bargaining and negotiation in a serious lawmaking process.

The reversion to courts independently analyzing each statute to determine its meaning is likely to introduce transaction costs, all other things equal (ceteris paribus). But as my game theory analysis suggests, ceteris is not paribus, and both Congress and agencies are likely to change their strategies and their actions if they want to achieve sound regulatory policy objectives.

This post originally appeared on Lynne’s Substack, The Knowledge Problem. Please consider subscribing here.