Ten years ago today I published a post at my sport governance blog, The Least Thing, that explored who had a greater chance of “going pro” — the men’s NCAA Division 1 basketball player or the PhD graduate seeking a tenure track job in a university? At the time it was a fun exploration of an interesting comparison.

In 2025, the comparison has taken on a deeper meaning.

Here is what I concluded in 2015:

Overall, the NCAA Division I basketball player has about a 3.5 times greater chance of playing professionally (at some level) than does the PhD in landing a job as a professor. The bottom line here is that the job market consequences of playing NCAA basketball are pretty similar to those of getting a PhD. Lots of people want to go pro, some are successful, but many are not.

Earlier this week I saw a news article in Nature that asked:

How many PhDs does the world need? Doctoral graduates vastly outnumber jobs in academia

That motivated me to update my analysis, a decade later, leading me to some broader considerations, reflected in this post.

The NCAA tracks the numbers of its players who go on to play professionally, and concluded in its 2024 report on men’s basketball players:

We estimate that 48% of the 2023 Division I draft cohort will compete professionally (NBA, G-League or internationally) in their first year post college (calculated as [46+540]/1,226). We also estimate that 63% of the 2023 draft cohort from the five Division I conferences with autonomous governance (ACC, Big Ten, Big 12, Pac-12 and SEC) will play professionally somewhere during the 2023-24 season (calculated as [31+111]/226).

For just the NBA — perhaps the equivalent to landing an R1 tenure-track faculty position — the odds of going pro are substantially less:

We estimate that 3.8% of draft-eligible Division I players were chosen in the 2023 NBA draft (46/1,226). Additionally, approximately 13.7% of draft-eligible players from the five Division I conferences with autonomous governance (ACC, Big Ten, Big 12, Pac-12 and SEC) were drafted by the NBA in 2023 (31/226).

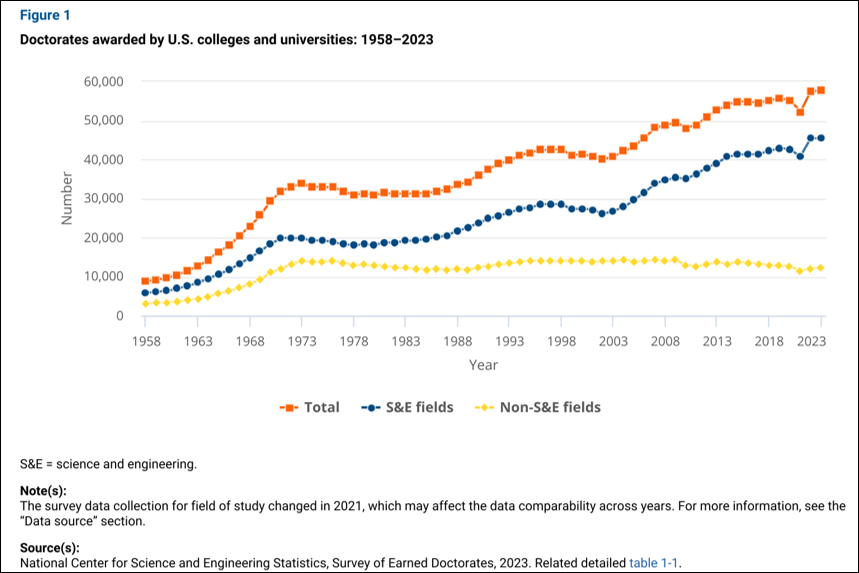

Let’s next take a look at U.S. PhD graduates and how many of them secure tenure-track faculty positions. According to the U.S. National Science Foundation, in 2023 U.S. universities graduated almost 58,000 PhDs, of which, ~46,000 were in fields of science and engineering. PhD production has increased steadily since the late-1980s, following a pause of about two decades, as you can see below.

NSF reports that a smaller proportion of newly-minted PhDs are starting their careers in academia (in non-postdoc positions, postdocs are decreasing also):

Doctorate recipients have shifted away from non-postdoc academic employment over time. In 2023, 34% of doctorate recipients with definite non-postdoc employment commitments in the United States reported that their principal job would be in academia, down from 54% in 2003. The proportion of doctorate recipients who reported non-postdoc employment commitments in academia in 2023 was highest in non-S&E fields (61%) and lowest in engineering (10%) and physical sciences (12%).

Many more PhD recipients are going to the private sector, with almost two third of PhDs in engineering and the physical sciences taking industry positions:

In contrast to the decline in definite non-postdoc employment commitments in academia, the proportion of doctorate recipients with non-postdoc commitments in industry or business in the United States more than doubled since 2003, comprising close to half (47%) of all 2023 doctorate recipient employment commitments.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the U.S. economy is expected to add more than 1 million new private sector, STEM jobs over the next decade. Not all of these will necessarily be PhDs, but many of them will be — meaning that continued production of PhDs and immigration of highly trained workers will be essential to keeping the U.S. economy humming along.

You can see from the numbers above that there is a bit of a conundrum here — the production of PhDs that will land in industry positions requires tenure-track faculty in universities to train them. A decrease in tenure-track faculty positions (whether intentially caused by policy or not) will necessarily have the effect of reducing the nation’s ability to produce highly skilled scientists and engineers.

Roy et al. 2024 looked at engineering PhDs and their odds of securing a tenure-track faculty position:

How likely are engineering PhD graduates to get a tenure-track faculty position in the United States? To answer this question, we analyzed aggregated yearly data on PhD graduates and tenure-track/tenured faculty members across all engineering disciplines from 2006 to 2021, obtained from the American Society of Engineering Education. The average likelihood for securing a tenure-track faculty position for engineering overall during this 16-year period was 12.4% (range = 10.9–18.5%), implying that roughly 1 in 8 PhD graduates attain such positions.

If anything, over the past decade the odds of becoming a tenure-track faculty member have become much longer than the odds of a NCAA Division 1 men’s basketball player going pro. I was surpised when I first learned this a decade ago.

Alone, this interesting fact might not signify much, as PhDs can certainly do as much for the world in the private sector as they can in academia. However, given the current turmoil in federal support for universities and STEM research and development, an intentional dismantling of the nation’s scientific capabilities is not without risk.

Vice President JD Vance has said that “universities are the enemy” and President Donald Trump echoed these comments:

We are going to choke off the money to schools that aid the Marxist assault on our American heritage and on Western civilization itself. The days of subsidizing communist indoctrination in our colleges will soon be over.

Universities, some of them at least, have gotten the message:

In their scramble to counter the Trump administration’s recent moves, universities have tried to tell elected officials and the public that they make important contributions to the country’s health and prosperity. They have also sought to frame university-based research as imperative to the nation’s future, especially as China gains global influence.

There is plenty of blame to go around for how MAGA Republicans and universities came to be at odds — which I discussed is some historical detail last week. There is also some truth in MAGA critiques and also in university responses. Pointing fingers and whataboutism is however not going to get science education or public R&D back on course. It is time for adults in the room (Hello Congress?) to assert themselves.

There is a reason why the NBA is the most incredible basketball league in the world. It is not because all Division 1 athletes go pro, but because of strong university commitments to athletics (love ‘em or hate ‘em) that produce the world’s best basketball players and an NBA that embraces the very best talent from overseas.

Policy makers should pay attention, or else the U.S. economy risks suffering the consequences of a lack of readily available PhD talent for indurties who need it, compromising innovation and growth. Universities can certainly do better training PhDs for careers in industry and policy makers can do better in supporting the U.S. R&D ecosystem.

Improve it, don’t burn it all down. This should be a slam dunk.