Last week I was contacted by two reporters at the Associated Press with a request to comment on the Department of Energy’s Climate Working Group (DOE CWG) report and the proposal by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to rescind the 2009 greenhouse gas endangerment finding:

We’re Seth Borenstein and Michael Phillis, reporters on the climate and environment team at The Associated Press. As you know last week, the Trump administration’s EPA proposed rescinding the 2009 Endangerment Finding on climate change. It did so with two documents. One was the actual EPA proposal and the other was the Department of Energy Climate Working Group’s “A Critical Review of Impacts of Greenhouse Gas Emissions on the U.S. Climate.” We have decided to ask the authors of every science-oriented reference in both documents about this. That’s why we are contacting you.

The reporters explained:

We are contacting well more than 100 scientists and experts like yourself to get a broad sense of the documents’ scientific accuracy so not everyone who answers will be quoted but if you do answer, and we would be appreciative, you will definitely help guide us to write a story with depth and authority.

With this post I am sharing the reporters’ questions and my answers. This allows THB readers to see how journalism is practiced on the “climate beat.” Once the AP writes their story, readers will be able to see how my replies are included, or not.

The reporters asked ten questions. Their questions, and my answers, follow.

- What do you think of the overall quality of the DOE and EPA reports?

The DOE CWG report was commissioned by the Secretary of Energy to “critically review the current state of climate science.” I do not interpret the report to be a comprehensive review of all of climate science, such as found in the assessments of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Instead, the report reflects the perspectives of five scientists who believe that certain topics within their areas of expertise have been neglected or underplayed in major climate assessments. As such, the report is a very high quality presentation of their views, and at the same time, the report largely overlaps with the findings of the IPCC.

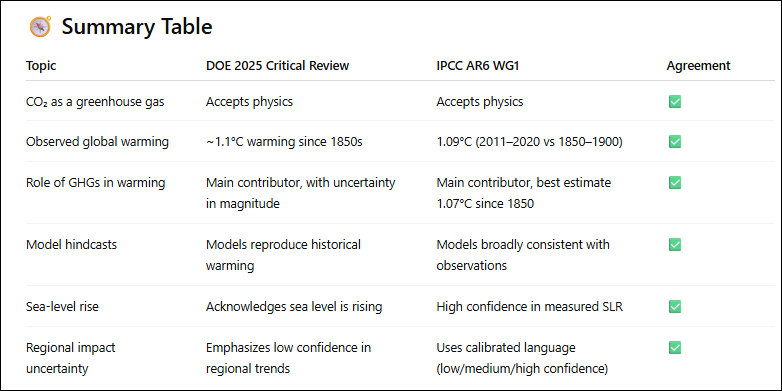

I asked ChatGPT to summarize areas of overlap between the CWG report and the IPCC AR6 Working Group 1 report. The results are summarized below, indicating substantial areas of agreement between the reports.

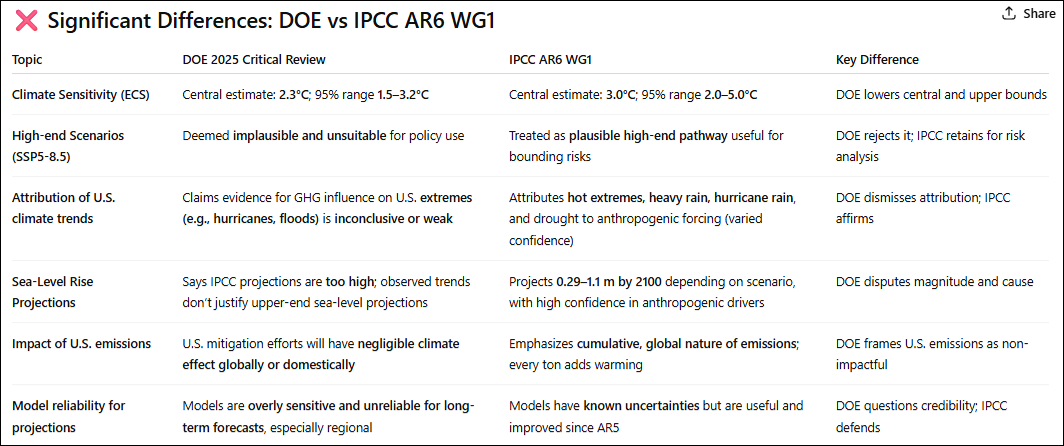

I also asked ChatGPT to summarize key differences between the reports, shown below. The differences are nuanced, and most cases reflect degree of emphasis rather than complete disagreement.

In my areas of expertise — climate scenarios and extreme weather — the DOE CWG report accurately summarizes the relevant literature, as I have documented for scenarios.1

The 302-page EPA proposal is almost entirely focused on legal arguments, with a few discussions of climate science (which I argue are not at all central to EPA’s case for reconsideration of the endangerment finding). You have called to my attention several of the scientific claims in the EPA proposal, and I discuss those below:

[R]educing GHG emissions from new motor vehicles and engines to zero would not have a scientifically measurable impact on global GHG concentrations and climate trends.

This is mathematically correct. Using conservative assumptions, new vehicles would emit at most ~3.3 billion tons of carbon dioxide to 2050, compared to projected global emissions, under a range of scenarios, of ~500 to 1,000 billion tons over the same period.2

[T]he Administrator has serious concerns that many of the scientific underpinnings of the Endangerment Finding are materially weaker than previously believed and contradicted by empirical data, peer-reviewed studies, and scientific developments since 2009.

The scientific community, including the IPCC, has acknowledged that the envelope of plausible emissions scenarios for the remainder of the 21st century are significantly lower (less extreme) that those considered plausible in 2009. That alone leads to less extreme projections of future climate change. However, the change is a matter of degree — changes in climate are still projected and will be accompanied by uncertain risks and certain impacts. I do not view the evolution of scientific understandings to provide a basis for rescinding the endangerment finding, as I have explained before.

With respect to [the 2009] endangerment [finding], the Administrator began by excluding adaptation – human responses that reduce potential adverse impacts – and mitigation – independent measures that reduce the causes of potential adverse impacts – from the analysis of global climate change concerns.

This is a very technical point that gets to the issue of how to construct a baseline or reference scenario to project the future, as part of the process of identifying potential risks and the effects of addressing those risks. In my view, plausible assumptions of adaptation and mitigation should certainly be included among the family of scenarios used to project futures. Their exclusion is not justifiable and leads to incomplete or misleading policy analyses.

The [2009] Endangerment Finding relied primarily on IPCC AR4 to predict global temperature increases between 1.8 and 4 degrees Celsius by 2100 . . . empirical data suggest that actual GHG emission concentration increase and corresponding warming trends through 2025 have tracked the IPCC’s more optimistic scenarios.

This projection comes from the IPCC SRES scenarios and the temperture values here are from a 1990 baseline. In terms of a preindustrial baseline the range is 2.5 to 4.7 degrees Celsius by 2100. There is a broad consensus that under current policies the world would be headed for the bottom of this range, or below. See Pielke et al. 2022. Climate projections have become less extreme. That does not mean that the issue has gone away, but that our perspectives have indeed changed.

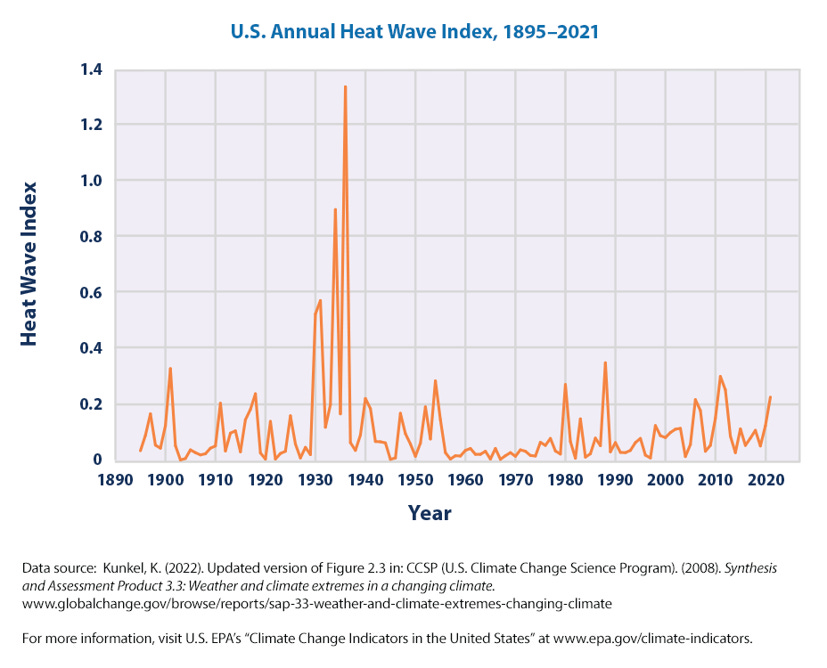

Notwithstanding increased public attention to heat waves, the data suggest that domestic temperatures peaked in the 1930s and have remained more or less stable, in relative terms, since those highs.

The figure above has been used by the EPA as an indicator of heat waves from 2008 to present, and is based on a paper I co-authored in 1999 (see Figure 11 in that paper). It is correct that the 1930s were most extreme by this metric, but it is also true that there has been a modest increase i heat waves since the low values of the 1960s and 1970s.

With respect to extreme weather events, the Endangerment Finding projected adverse health impacts from increased frequency and severity of hurricanes, flooding, and wildfires. E.g., 74 FR 66498. Recent data and analyses suggest, however, that despite increased public attention and concern, such extreme weather events have not demonstrably increased relative to historical highs . . .

As written, this statement is correct with respect to hurricanes and floods. I would have recommended more nuance when it comes to wildfires. It is true that North America has a considerable fire deficit, due to fire suppression over many decades. However, a considerable literature has established that climate conditions matter for fire occurrence and severity, and human-caused changes in climate also play a role. Quantifying specific attribution in the context of the many factors that affect fire trends is incredibly challenging, but qualitatively, a linkage of greenhouse gas emissions with factors that influence wildfire is well established.

Based on this review of the Endangerment Finding and the most recently available scientific information, data, and studies, the Administrator proposes to find, in an exercise in discretionary judgment, that there is insufficient reliable information to retain the conclusion that GHG emissions from new motor vehicles and engines in the United States cause or contribute to endangerment to public health and welfare in the form of global climate change.

This is a judgment call. I disagree with EPA’s argument for reconsideration as a matter of law — I do not think science plays much of a role.

In Massachusetts vs. EPA (2007) which set the stage for the 2009 endangerment finding, Justice Stevens wrote for the majority:

In sum—at least according to petitioners’ uncontested affidavits—the rise in sea levels associated with global warming has already harmed and will continue to harm Massachusetts. The risk of catastrophic harm, though remote, is nevertheless real.

The threshold for endangerment under the Clean Air Act (CAA) is very low. The reality of sea level rise resulting (at least in part) from greenhouse gas emissions is sufficient to find endangerment. Such a finding does not compel particular regulations (or regulation at all), and is a consequence of the broad language of the Clean Air Act. The science summarized in the DOE CWG report is sufficient to find endangerment under the CAA.

- Did the sections of the report(s) that cited your work accurately and fairly portray it? Please elaborate.

- Do the overall conclusions of the documents accurately portray the overall conclusions of your general body of work? Please explain why or why not.

I have documented this in detail in a previous post here at THB. The short answer is “Yes, our work has been accurately and widely cited in the DOE CWG report.”

- Does the overall work and conclusions of the documents accurately portray the current, mainstream view of climate science? Please feel free to give details and explain what you consider important or not about this.

The IPCC assessments include thousands of discrete findings across many areas of climate research. Associated with each of these findings are a distribution of legitimate views among relevant experts. For some findings the distribution of expert views found in the literature is very narrow — such as the warming effect of accumulating carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. For others, the distribution of expert views might be very wide with no central tendency — such as projected possible changes in flooding around the world to 2100.

The science summarized in the DOE CWG is largely consistent with the findings of the IPCC, though in some cases the authors have legitimate views based on their expertise that they believe have not been adequately represented by the IPCC. That is neither unusual nor unexpected, but how science works. For my part, for example, I do not believe that the IPCC has yet adequately recognized the significance of changing perspectives on scenarios, although these changes were acknowledged in IPCC AR6 WG1.

The IPCC is not a sacred text that can be used to identify believers and apostates. Weaponizing the notion of “mainstream” to dismiss or denigrate legitimate scientific views that one does not like is contrary to how science advances — through challenge, debate, discussion, and not gatekeeping.

- Was the selection of sources sufficiently current and representative of the best available science?

As I explained above, I do not interpret the DOE CWG to be attempting to be representative of all of climate science, but instead a small group of authors making a case for overlooked or underplayed issues.

- Do you consider the work and conclusions of the document to be biased in any way, or not? Please explain with examples.

Of course. The report is the authors’ perspective on what has been overlooked in formal scientific assessments. These scientists are extremely accomplished and legitimate participants in discussions of climate science, even if other scientists disagree with their work or how that work is used in political settings.

- On a scale of 0 to 100 with 100 being the best, how would you rate the EPA report? What about the DOE report?

If the goal of the DOE CWG report is to open up discussion of various aspects of climate science then the report certainly gets an “A.” Consider that this is the first time that the AP has contacted me for comment in years,3 if not decades, and I am among the most published and cited researchers on extreme events and their impacts in the United States.

Would you guys be contacting me if I wasn’t one of the most cited researchers in the report?

The EPA “report” is a legal document outside my expertise, but from my perspective as a policy scholar, no matter how well argued, I think EPA faces an uphill battle in overturning the endangerment finding as a matter of law.

- If you were teaching an undergraduate class and your student delivered the EPA document as an assignment, what grade on the standard A to F scale would you give it? Why?

- If you were teaching an undergraduate class and your student delivered the DOE document as an assignment, what grade on the standard A to F scale would you give it? Why?

These are absolutely ridiculous questions and suggest that your goal here is not journalism but team sport.

- Any other thoughts?

I look forward to your reporting! Thanks for contacting me.

1 I will have a future post on how the DOE CWG report discusses extreme weather.

2 Methods: I took the EIA AEO 2025 Reference Case for projected annual sales of new ICE automobiles to 2050 (~50 million), assuming each remains on the road through 2050 and emits an average of 4.6 tons of carbon dioxide annually (EPA 2023).

3 It is not just the AP. The New York Times contacted me last week on climate for the first time in a decade.