Adaptation to climate has long been disparaged by climate advocates. Adaptation has been framed as an avoidable cost of the failure to mitigate, fundamentally limited in its effectiveness in reducing climate impacts, and an obstacle to efforts to promote emissions reductions.

In a major new paper, published as a pre-print, we have a new analysis of adaptation — Burgess et al., The Economics of Climate Adaptation Optimism — that makes the case that the narratives promoted by climate advocates, found across the academic literature, and in the assessments of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), “often invert reality.”

Specifically, we argue:

Mitigation remains a crucial long-term goal for society—the Earth will continue to warm until emissions reach net zero. However, adaptation—especially via economic development—is the dominant proximate driver of many, if not most, climate-sensitive societal outcomes. Adaptation and development have led to broad long-term improvements in crop yields, affluence, damage and death rates from climate-related hazards, and mortality from violence and self-harm, despite these outcomes’ marginal sensitivities to climate. This success, despite limited attention and resource allocation, underscores the potential of adaptation to reduce climate risks, and the importance of prioritizing economic development in solutions to climate change.

Adaptation and mitigation are not trade-offs — or at least they should not be framed as trade-offs — as each influences outcomes on incommensurable scales of space and time.

Costs and benefits of adaptation efforts are closely matched in time and space. Consequently, we show that adaptation’s benefits to climate-sensitive outcomes often exceed those of mitigation by orders of magnitude on small-to-medium space and time scales. This can make markets and local governance powerful allies of adaptation. Mitigation efforts that provide immediate economic benefits—such as improving energy efficiency and deploying cheap renewables—have similar advantages. In contrast, mitigation efforts that pose short-term or local costs face cross-regional and intergenerational coordination challenges, due to their diffuse benefits in time and space. Costly mitigation efforts might also undermine adaptation, given the strong link between adaptation and development.

We define adaptation broadly:

We use a broad outcome-based definition of adaptation, including any policy, investment, technology, behavior or institutional change that—regardless of intent—measurably improves climate-sensitive outcomes (e.g., mortality, economic damages, crop yields). This includes both targeted risk-reduction (e.g., building codes, levees, urban cooling, early warning, air-conditioning access, and grid reliability) and broad human development that lowers vulnerability (e.g., infrastructure quality, health systems, education, and general poverty reduction) and is typically associated with affluence.

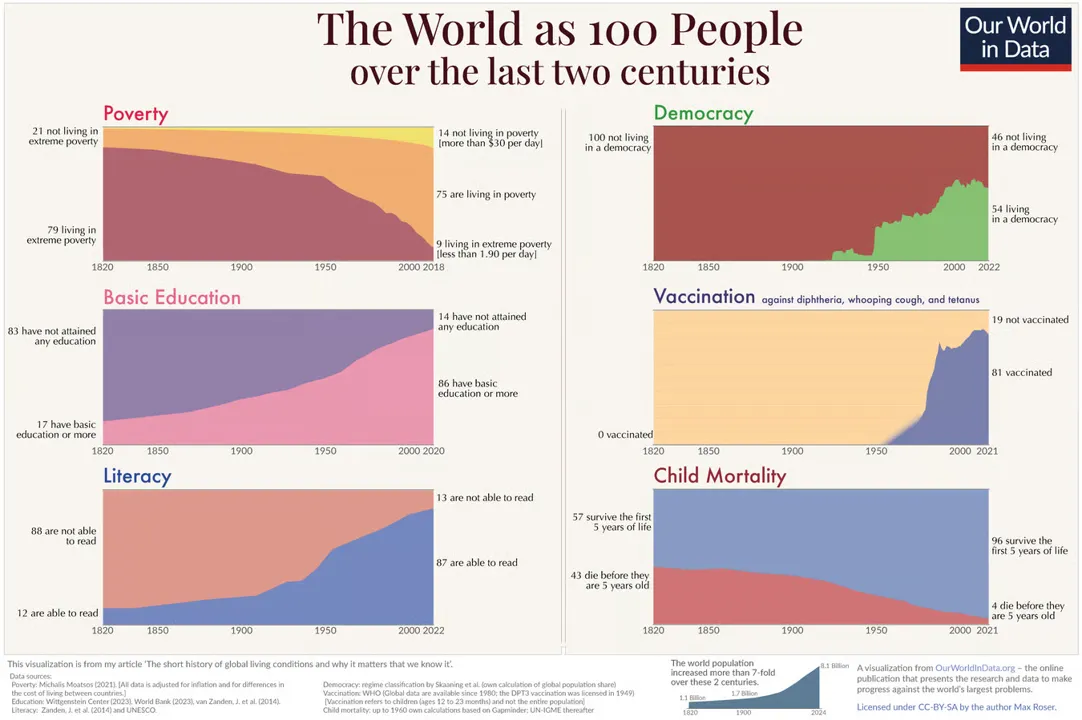

Across an incredibly wide range of metrics, humanity has successfully adapted itself to life on planet Earth in ways that show undeniable improvement, with considerable room for greater improvements. We include a wide range of such metrics in our paper, similar to the excellent visualization below from Our World in Data.

A big part of our paper involves mathematically formalizing our thinking about how adaptation influences outcomes. That section will appeal to economists and the more math-inclinded readers.

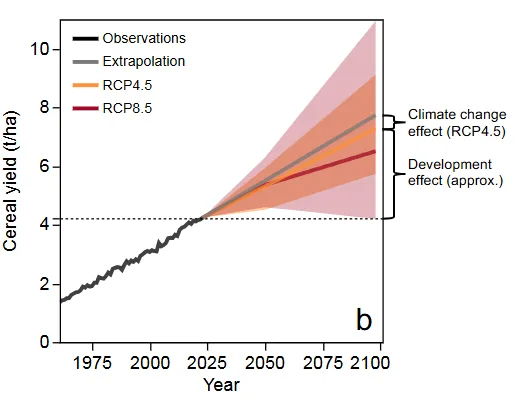

But one does not need math expertise to understand our analysis, with an example visualized in the figure below. The figure shows that the projected impact of climate change on cereal yields is dwarfed by the effect of development, based on analyses found in the literature and combined in our paper.

Note: A comparison of global cereal yields under climate change, projected by Hultgren et al., compared to 1961-2023 historical trends and a linear extrapolation (from Teixeira). Shaded regions represent 90% confidence bounds. You can also see in the figure why RCP8.5 is typically preferred in showing the marginal impact of climate change.

In this example, in the broader context of development, the projected impact of climate change is relatively small, even if marginally large. This example is more broadly representative. Beware analyses that hold society constant and just look at sensitivities to posited long-term changes in climate — trees and forests.

From our paper, we arrive at several conclusions based on the analysis:

- Development trends typically pull climate-sensitive societal outcomes in beneficialdirections faster than climate change pulls them in deleterious directions;

- The more locally one zooms in geographically, the smaller the benefits of local mitigation become, compared to adaptation;

- Costly mitigation efforts pit the interests of most people alive today against those of most people not yet born, which is politically daunting, even if it were to be judged optimal in the long view;

- If the damage and death rates from climate hazards decrease by 0.5% for every 1% increase in real GDP per capita there could be many scenarios where costly mitigation results in more harm to climate-sensitive outcomes via reduced adaptation and development than benefits via lower emissions;

- Well-intentioned but costly climate mitigation policies risk deepening the challenges faced by the world’s poor.

I have commonly encountered arguments from climate advocates — those who are not degrowthers — who suggest that a reduction in global GDP growth would be a small price to pay for emissions reductions.

In a recent social media interaction I quoted the following prompt and reply from ChatGPT:

Prompt: At the global level, assume a 1% reduction in GDP growth rate over 30 years. Estimate excess deaths for infant mortality, under-5 mortality, and all-cause mortality.

Reply: A sustained 1 percentage-point reduction in global GDP (or GDP per capita) growth over 30 years implies large compounded income losses (≈25% lower income levels by year 30). Using established income–mortality relationships, especially from child-survival research in low- and middle-income countries, this slowdown would plausibly lead to ~9–13 million excess infant deaths and ~12–18 million excess under-5 deaths globally over the period. Because under-5 deaths are included in all-cause mortality, a consistent global estimate implies ~12–44 million excess all-cause deaths over 30 years, with uncertainty driven mainly by how slower long-run growth affects adult mortality in different income settings.

GDP growth is certainly not everything, but it is something.

The implications of our analysis are clear:

Most climate-sensitive societal outcomes have been steadily improving in most regions, and economic development has been the dominant driver of these trends, making economic development a key source of climate adaptation. Given that mitigation has spatially and temporally diffuse benefits, we showed that any mitigation effort with local and immediate economic costs could have adverse immediate and local effects on climate-sensitive outcomes, in addition to their adverse effects on the economy. In contrast, adaptation and economic development have local and immediate benefits to both affluence and climate-sensitive outcomes. In this light, policymakers—who generally operate on local and near-term time scales—should strongly prefer adaptation to costly mitigation, if the policy objective is to improve climate-sensitive outcomes.

Take note however that this conclusion does not mean that reducing emissions makes no sense. To the contrary, we argue that to be effective mitigation policies should learn lessons from successes in adaptation — notably the alignment of the time and space scales of costs and benefits.

We note that there are,

. . . already-abundant approaches to reducing GHG emissions that either create immediate economic benefits or develop world-leading exportable technologies represent opportunities to advance mitigation outside of the challenging tradeoffs with development and adaptation described above.

Here is how we conclude:

Research, policy and public discourse on climate change primarily focus on mitigation (i.e., reducing GHG emissions). Academic and popular narratives are often pessimistic, sometimes verging on apocalyptic and/or Manichean.

In contrast, trends in most climate-sensitive outcomes—such as crop yields, affluence, damage and death rates from climate-related hazards, and mortality from violence and self-harm—are improving in most world regions. These improvements have been largely driven by economic development and the corresponding opportunities for better infrastructure and technology, and more effective decision making that lead to improved adaptation to climate variability and change. On policy-relevant time scales, continued improvements in these outcomes, despite climate change, will be driven predominantly by continued progress in economic development and adaptation. Even in the most optimistic GHG emissions scenarios, society will need to adapt to equally warm or warmer climates than we experience today.

Therefore, climate change research and policy should place greater emphasis on adaptation and economic development. Adaptation and mitigation should be viewed as complementary approaches to addressing climate change, addressing different aspects of the problem on different space and time scales. However, the importance of economic development to innovation, climate-sensitive outcomes and broader well-being calls for cautious approaches to costly climate policies, and ambitious approaches to R&D. Links between economic development, environmental sustainability and human well-being should remain a priority for future research.

You can read the whole pre-print here: Burgess et al. The economics of climate adaptation optimism. It will be submitted for publication soon.