An important new paper published this week in Nature Communications looks at the historical record of fire in North America — A fire deficit persists across diverse North American forests despite recent increases in area burned. Parks et al. find that large fires of recent decades in North America are not unprecedented:

Our study of 1851 tree-ring fire-scar sites and contemporary fire perimeters across the United States and Canada reveals a substantial, persistent fire deficit from 1984–2022 in many forest and woodland ecosystems, despite recent increases in burning. Contemporary fire occurrence is still far below historical (1600–1880) levels at NAFSN [North American tree-ring Fire-Scar Network] sites despite multiple large and ‘record-breaking’ recent fire years, such as 2020 in the western United States. Individual years with particularly widespread fire during the 1984–2022 period were not unprecedented in comparison with the active fire regimes of the historical period across most of the study region. Historically, fires in particularly active fire years were spatially more widespread and ubiquitous compared to fires burning during active contemporary years.

I’ll get back to the paper’s important findings in a moment, but first let’s take a look at comments from the paper’s peer review file, which Nature Communicationshelpfully publishes alongside the paper.

Reviewer 2 asks the authors to change their emphasis, lest their results get “used by deniers”:

I see this paper as potentially being used by deniers of climate change impacts. Consider if possible some rephrasing here to put even more emphasis on impact rather than on burned area.

The authors respond as they must in contemporary climate science:

We share the concern that climate change deniers may misuse our findings.

Note how the authors subtly recast Reviewer 2’s concern about “use” of the paper to a more appropriate concern about “misuse.” Of course, concerns about how one’s political opponents might use or misuse a paper should have no bearing on peer review — ideally, but not in today’s climate science. Ironically, this paper performs no analysis of changes in climate or climate impacts, making the Reviewer 2’s concern all the more inappropriate.

Even so, the paper made it through peer review. However, this vignette illustrates the ever-present political overlay on climate research — Do not give oxygen to climate deniers!

Now back to the paper.

The authors start by asking an important question (emphasis added):

[A]verage annual area burned since the late 19th and early- to mid-20th centuries is generally less than that experienced under historical fire regimes across many North American forests, resulting in a widespread 20th century ‘fire deficit’ relative to earlier time periods. However, area burned by wildfire has increased across much of North America over the last few decades. Over this time period (mid-1980s—present), several regions have experienced individual years with exceptionally high area burned, leading to questions about whether recent fire years are unprecedented. As area burned has increased rapidly since the mid-1980s in parts of North America, is it possible that the fire deficit has been reduced or eliminated?

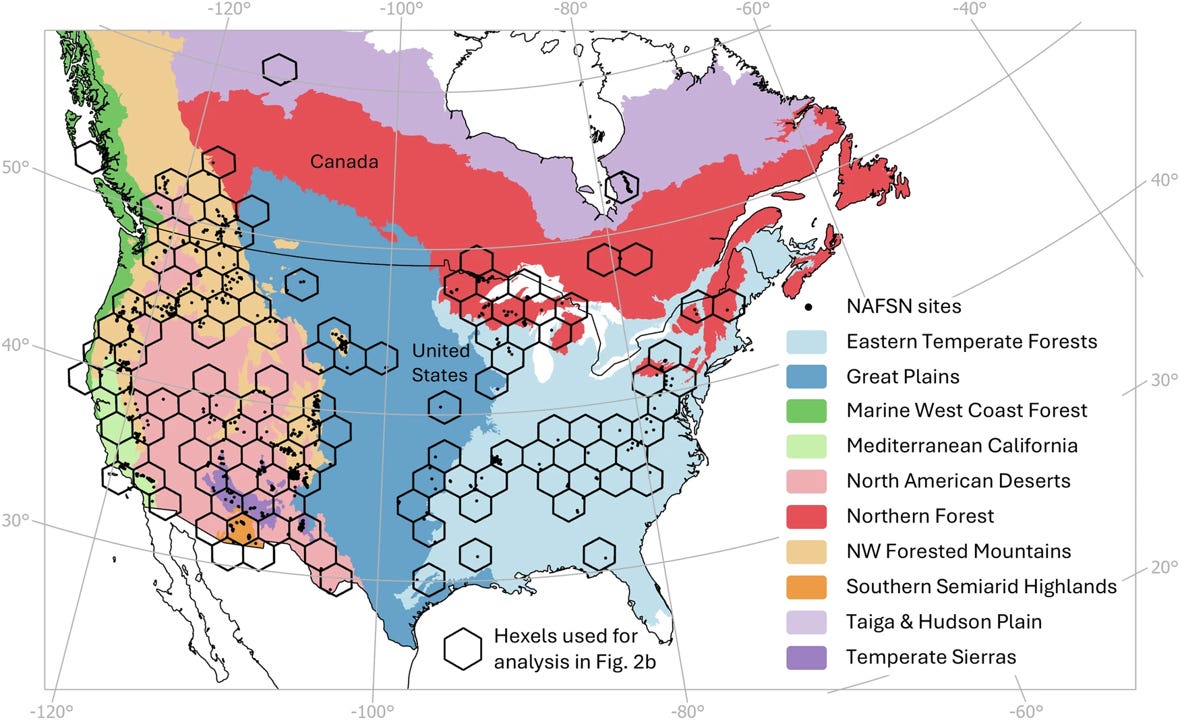

To answer this question they look at a novel dataset on tree-ring scars caused by fire. The map below shows with hexagons the areas covered by the study.

It is not often that I am reading a scientific paper and encounter results that make me say — “Wow!”. This is one of those cases:

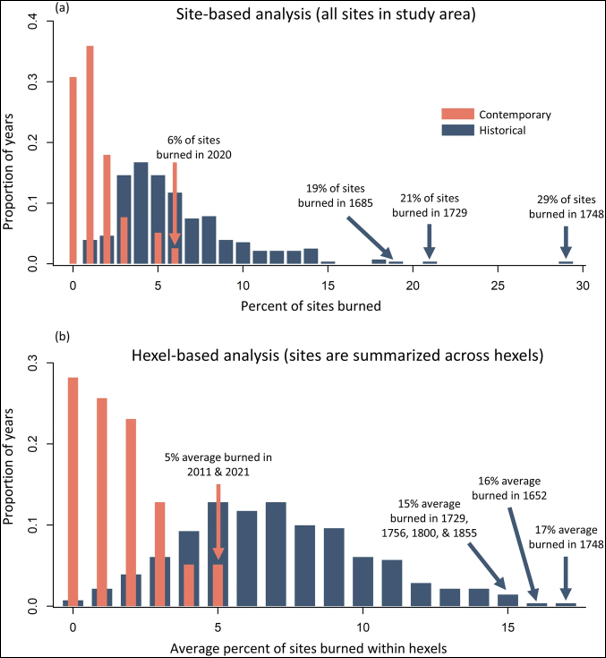

The year 2020 had the highest percent of sites recording fire in the contemporary time period, with 6% of NAFSN sites burned. This percentage is far below the 29% burned in the most widespread historical fire year (1748) and equal to the average of 6% that burned per year across NAFSN sites during the historical period.

Wow!

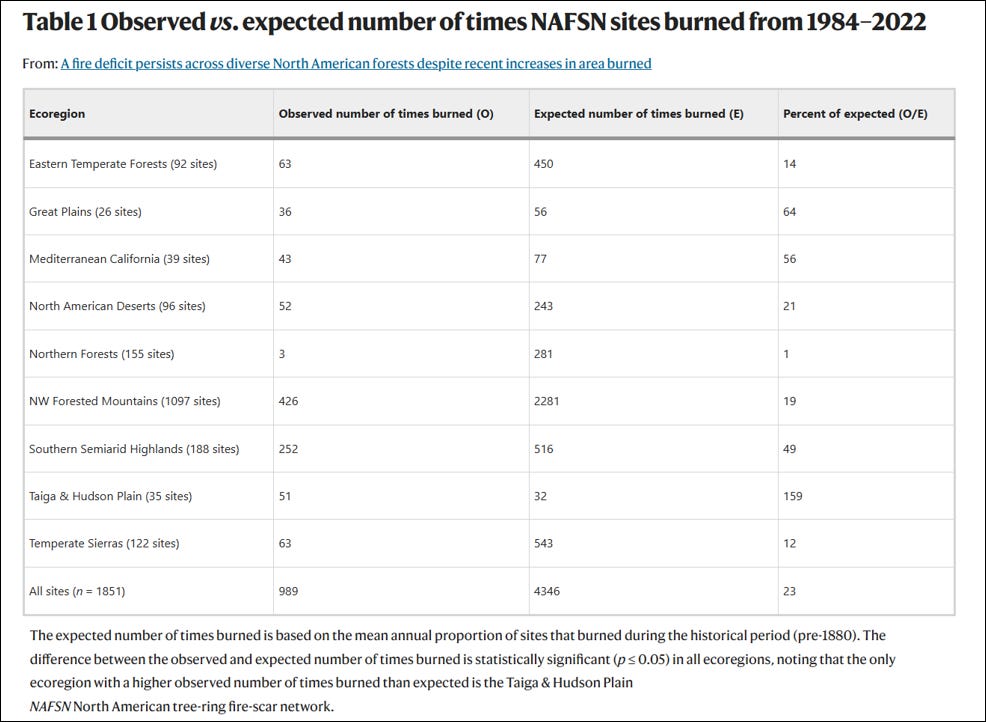

The table below shows the magnitude of the fire deficit by region, which varies a great deal. Overall, fires occurred at a rate of only 23% of that expected based on historical fires — indicating a huge accumulated deficit.

The figure below puts rates of contemporary fire occurrence into historical context with histograms showing the contemporary fire distribution (in orange) versus historical (in dark blue). You don’t need to be a statistician to see the incredible shift in the distribution, indicating the large fire deficit.

What caused the fire deficit? Parks et al. explain:

Our evidence indicates that, even under a warming climate, the rate at which NAFSN sites burned in recent decades has been much lower than historical rates across most of the continent. We attribute this disparity to aggressive fire suppression, disruption of traditional burning, and forest loss and fragmentation from land development and other land uses (e.g., conversion of forests and woodlands to agriculture). Although the substantial reduction in contemporary fire activity compared to historical time periods may seem desirable, it has greatly altered forest composition, structure, and continuity, in many respects adversely.

The large fire deficit is thus human caused. The authors note that human-caused changes to forests resulting from fire suppression have led to more severe fires when they do occur:

In many western North American forests, particularly those represented by the tree-ring fire-scar sites analyzed here, heavy fuel loads and increased fuel continuity have developed because of fire exclusion, thereby increasing fire severity when forests inevitably burn. Contemporary fires include more high-severity fire (i.e., high tree mortality) as a proportion of total area burned, and high-severity patches are becoming larger and more connected. . . Therefore, even though less fire is occurring than expected under a historical fire regime, contemporary fires are likely unprecedented when viewed through the lens of their severity and ecological impacts.

The large human influence on forests does not mean that the climate has not changed in ways that also influence fires, but it does mean that the management (intentional or not) of ecosystems has played a much larger role in shaping fire behavior than has any plausible effect of greenhouse gas emissions on climatic conditions that favor fire.

This is obvious via some simple math — Consider Figure 2a above which shows that 6% of sites burned in 2020. Let’s just assume that without changes in climate caused by greenhouse gas emissions this number would have been just 3%. So in this thought experiment climate change doubled the number of sites burned.

However, in the absence of contemporary changes in climate, 29% of sites burned in 1748. That means that human changes to forest ecosystems were about an order of magnitude more important than assumed human-caused changes in climate (i.e., 29%-to-3% versus 3%-to-6%).

Of course, this thought experiment dramatically overstates the expected role that changes in climate play in fire occurrence — meaning that in the real world forest management is certainly much more than an order-of-magnitude more important. The implications for the popular parlor game of pointing to “climate” as a cause of recent fires are thus profound — we are missing the forest for the trees.

Parks et al. suggest that North America needs more — much more — fire on the landscape (emphasis added):

Specific actions include substantial increases (10- to 100-fold) in prescribed fire, mechanical thinning combined with prescribed fire, and managing fire as an ecosystem process in locations and times of year when it is safe to do so. Such preemptive actions will increase the probability that future unplanned fires will be less disruptive to society and forest ecosystems (i.e., lower severity fire), thereby allowing us to better co-exist with fire, as did traditional societies long before the disruption of historical fire regimes.

Parks et al. recognize explicitly that their findings run counter to a popular narrative (somewhat ironically, that some of the paper’s coauthors have helped to promote) that climate change is fueling an unprecedented increase in fires, and by extension, that we should expect less fire in a world with mitigation policy success.

Many studies have reported increases in area burned associated with a warming climate over the last few decades across much of North America. Considering these studies, forest managers and the general public may be surprised to learn that a significant fire deficit persists in many forested ecosystems even as contemporary socio-economic fire impacts are increasing.

Climate change is of course real and poses risks. Accelerated decarbonization of the economy makes good sense for many reasons beyond just climate change.

However, modulating future forest fires is not among those reasons that make good sense. There is no carbon dioxide emissions control knob that can be used to moderate fire occurrence or severity (as some seem to believe).

In fact, the incredible fire deficit across almost all North American landscapes suggests — as Parks et al. argue — that the best way to moderate future fires is through better forest management, including much more fire.

This post was originally pubished on Roger’s Substack, The Honest Broker. If you enjoyed this piece, please consider subscribing here.