Over the past few years, I have watched my parents, family, and friends retreat from online spaces. They used to comment on political issues online; now they just lurk.

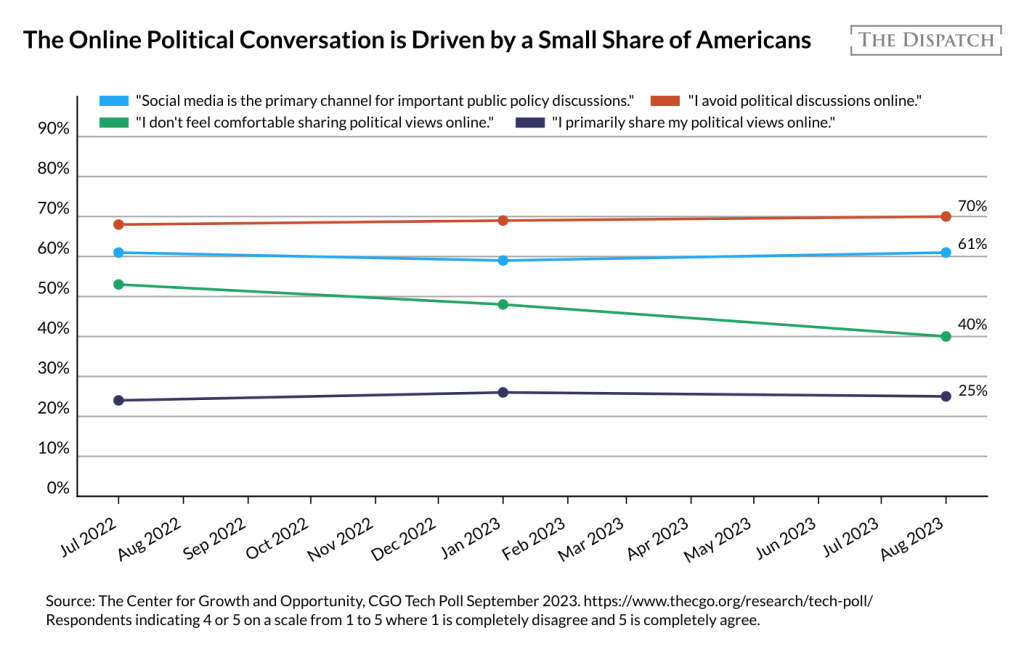

So a couple of years back, while working at the Center for Growth and Opportunity at Utah State University (CGO), I made sure we asked a series of questions about tech use when we ran our biannual tech poll. We gave participants four statements and asked them to indicate how much they agreed or disagreed with the statement. Here are the statements:

- “I feel comfortable sharing my political views on social media.”

- “Social media platforms have become the primary channel by which important public policy conversations are taking place.”

- “I primarily use social media to share my political beliefs with others.”

- “I avoid political conversations online.”

The results were what I expected and have remained persistent over subsequent polls. Over two-thirds (70 percent) of people actively avoid political conversations online. While people increasingly feel comfortable sharing political ideas online, for the vast majority, social media is not where they share political ideas (75 percent). If they are doing it, they are doing it in casual settings. But more than likely, they are mostly silent on these topics.

The findings from CGO’s tech polling aren’t unique. Pew also recorded a similar trend when it polled voters just before the 2020 election. Some 70 percent of U.S. social media users never or rarely posted about political and social issues. Rather, a small group, just 9 percent, is talking about politics all the time. And this group tends to lean either very Democrat or very Republican. Moderates are underrepresented in social media.

Political content isn’t the only area where a small group is vocal. Power laws dominate the overall production of what you see online. For example:

- The most prolific 10 percent of Reddit users create 80 percent of all the content.

- Dr. Itai Himelboim, assistant professor at the University of Georgia Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication, found that “about 2 percent of those who start discussion threads attract about 50 percent of the replies.”

- An analysis of Reddit found that the top 1 percent of users wrote 40 percent of the comments.

- NPR disabled comments on its website after finding that more than half of all comments in a three-month period came from just 2,600 users. In some months, the service cost NPR twice what was budgeted, and served a small part of its overall audience.

- Wikipedia too is largely the product of a small minority, as 77 percent of entries are written by 1 percent of users.

- Although the stat is from an older report, 8 percent of internet users account for 85 percent of ad clicks.

Most of what you see online, therefore, is often a loud, small, partisan minority. In turn, this group can misshape an individual’s perception of the general public, leading to the misconception that some beliefs are more common than they really are. Production inequality on the internet skews the discourse, making it seem as though the public is far more divided than it actually is.

Information scientists Kristina Lerman, Xiaoran Yan, and Xin-Zeng Wu call this feature of social networks the “majority illusion.” As they explained in a 2015 paper, “In some cases, the structure of the underlying social network can dramatically skew an individual’s local observations, making a behavior appear far more common locally than it is globally.” They continued: “As a result of this paradox, a behavior that is globally rare may be systematically overrepresented in the local neighborhoods of many people, i.e., among their friends.” In other words, our perception of what we see online often makes us overestimate the popularity of certain ideas.

Recent controversies on TikTok appear to lend credence to this deceptive notion. Last November, various outlets reported that young TikTokers were sharing Osama bin Laden’s manifesto. But when John Herrman looked into the trend, he found just “a few dozen results” for the manifesto. He concluded that it was a case of overstated virality. Just like NyQuil chicken a year earlier.

On September 15, 2022, the Food and Drug Administration published a statement warning about a new trend of cooking chicken in NyQuil. But until the statement, there were only a handful of searches for the idea on TikTok, quite literally. As first reported by Buzzfeed News, TikTok only saw five searches for NyQuil chicken on its platform the day before the FDA published its statement. By September 21, there were roughly 7,000 searches. As Lerman, Yan, and Wu explained in the original paper, the majority illusion helps to “explain why systematic biases in social perceptions, for example, of risky behavior, arise.”

This bias also goes a long way to explain why trolls have such a significant effect online. It only takes one individual to sour the digital experience for many. Indeed, just 1 percent of Reddit accounts are responsible for three-fourths of the platform’s confrontational interactions. Research from the Anti-Defamation League tracked antisemitic tweets in 2015 and found that two out of three came from just 1,600 accounts. Similarly, one report suggested that most vaccine misinformation was being spread by only 12 people.

The widely accepted interpretation has it all wrong. The internet doesn’t make people monsters. Rather, a minority of online miscreants degrade the experience for the broader community. Penn professor Ethan Mollick summarized it nicely when he said, “Political discussions are hostile because the people who like to engage in political discussion are largely hostile people. You just didn’t see it until we were all online.”

The majority illusion in all of its variants has a real-world impact. As I wrote a couple of weeks back, new research from Bailey, White, Iyengar, and Akinola once again confirms that people overestimate how often their peers engage in political debate. As they were clear to point out, “overestimating how often Americans debate strangers online significantly predicted greater hopelessness in the future of America.” Consequently, the illusion of a debate-saturated society could be unjustly diminishing Americans’ hope for the future.

The majority illusion also might be to blame for the distance that exists between political elites and the general public on key policy issues. Nate Cohn’s writeup of a poll run by the New York Times and Siena in October 2022 illustrated this:

When we started our national poll on democracy last week, David Leonhardt’s recent New York Times front-page story on threats to democracy was at the top of my mind. His article focused on two major issues: the election denial movement in the Republican Party, and undemocratic elements of American elected government like the Electoral College, gerrymandering and the Senate.

But when we got the results of our Times/Siena poll late last week, it quickly became clear these were not the threats on the minds of voters.

While 71 percent of registered voters agreed that democracy was “under threat,” only about 17 percent of voters described the threat in a way that squares with discussion in mainstream media and among experts — with a focus on Republicans, Donald J. Trump, political violence, election denial, authoritarianism, and so on.

Instead, most people described the threat to democracy in terms that would be very unfamiliar to someone concerned about election subversion or the Jan. 6 insurrection — and I’m not just talking about stop-the-steal adherents who think the last election already brought American democracy to an end.

It was corruption that people cared about, whether the “government works on behalf of the people,” rather than a more esoteric notion of democracy.

Not long ago, Derek Thompson called the majority illusion “one of the most important political ideas” for understanding our current media ecosystem, and I think he is right. Since reading about the majority illusion back in 2015, I have seen my own thinking change, as my inner voice now constantly demands I dig deeper and question what I perceive to be correct. Among the questions I try to ask: Am I overrepresenting an idea or event? Do I perceive something that is not there?

To top it off, the total number of X/Twitter users seems to have shrunk, so what gets traction on that social media site is likely to be even more niche than before. As the 2024 election season heats up, thoughtful folks of all stripes would benefit from internalizing the concept of the majority illusion. Or, to say it more simply, the Twitter electorate isn’t the real electorate.