With the end of the war against COVID-19 now in sight, the National Science Foundation has become a battleground in the fight over the future of federal science funding. Tucked away in President Biden’s $2.3 trillion infrastructure plan is a $50 billion funding increase for the National Science Foundation (NSF) — over $40 billion more than the agency’s annual budget.

The Biden plan is a nod to Sen. Schumer’s Endless Frontier Act, released last year and under consideration again this week. The bill calls for $100 billion to create a new directorate within NSF focused on technology innovation and a regional technology hub program focused on “key technology fields of the future.” It has proved controversial, since NSF’s primary purpose is basic science funding, rather than technological development. Some scientists worry that the plan could dilute NSF’s core mission and create tensions within the agency.

Such debates over the structure of NSF are nothing new. On the contrary, they rehearse a dispute that took place over 75 years ago in the lead up to NSF’s creation, as the country was emerging from another war in which the federal government’s role in science and technology proved decisive: World War II. This history offers lessons policymakers should heed today.

The NSF was the brainchild of Vannevar Bush, President Franklin Roosevelt’s science advisor. Bush oversaw the nation’s wartime research, which enjoyed unprecedented levels of federal funding. Bush wanted to ensure that such support would continue during peacetime. Accordingly, at the request of the president, he prepared a report, “Science—the Endless Frontier,” calling for a National Research Foundation to fund science to spur innovation.

In fact, Bush suggested the idea of the report to the president himself, in an effort to gain the upper hand in an ongoing debate. The debate was with Sen. Harley M. Kilgore, who had been calling for the creation of a National Science Foundation to address the nation’s most pressing problems. Bush was an East Coast Republican, Kilgore a New Deal Democrat from West Virginia. And while both wanted to keep government involved in science, they disagreed about how.

Bush wanted the new agency to fund basic science, Kilgore, applied research and development. Bush believed that funds should be rewarded on a meritocratic basis, Kilgore preferred a geographical distribution. Bush wanted research to be free of government “control.” For this reason, he proposed that the agency director be appointed by representatives of the scientific community; Kilgore wanted the director to be appointed by the president. Bush’s system of “support without control” was designed to leave science free to flourish, insulating it from political interference and practical pressures. Kilgore’s system, by contrast, was designed to steer science toward solving practical problems, ensuring political accountability and social utility.

After five years of congressional debate and a presidential veto, the National Science Foundation was created in 1950. Despite Kilgore’s name, the NSF would use federal dollars to fund basic research in the nation’s universities, as Bush proposed. But the director would be appointed by the president, as Kilgore proposed.

So who won?

Although the NSF director is appointed by the president, the agency’s organizational structure clearly bears the imprint of Bush’s plan. Moreover, both the idea that government should support basic science to stimulate innovation and the system of federal grants for “extramural” research have since become bedrocks of U.S. R&D policy. For this reason, it is often said that Bush — and not Kilgore — wrote the playbook for federal science funding in the modern era. But this isn’t quite right.

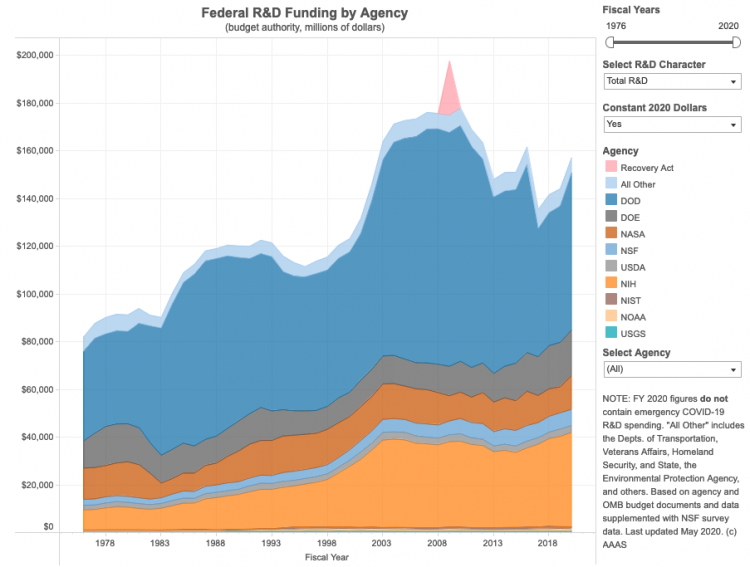

Bush had wanted his science agency to oversee all government research. Yet, by the time of its creation, the NSF was only one of many federal agencies that funded science — and hardly the largest. Rather, the Department of Defense, the Atomic Energy Commission, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and the National Institutes of Health would come to dominate federal research. Thus, rather than a clearing house for all federal science, the NSF was “only a puny partner in an institutionally pluralist federal research establishment,” as historian Daniel Kevles put it.

This research establishment emerged in the 19th century in response to practical government needs — collecting demographic information, improving mineral extraction and agriculture, charting the country’s waters and mapping public lands. Despite Bush’s paeans to basic science, the post-war decades continued — even accelerated — this trend. Under pressure from Cold War priorities, federal funding skewed heavily toward applied research and development after the war, most dramatically illustrated by the Apollo Program.

Federal funding also skewed heavily towards defense, exemplified by the creation of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency in 1958 in response to Sputnik. But Bush, while recognizing a role for military research, had wanted most federal research to be transferred over to civilian hands. He worried that defense research would be excessively utilitarian in focus. Such worries would be vindicated when, in 1967, the Defense Department released an influential report that took a dim view of the “cost-effectiveness” of “undirected research.”

Later in the century, private-sector R&D spending would begin to outpace federal. Today, industry vastly outspends government — a complete reversal of what Bush wanted. The problem, he said, was that industry is “generally inhibited” by the “constant pressure of commercial necessity.” And, indeed, almost all private-sector R&D funding today goes to product development, rather than basic research. As a result, the U.S. R&D system overall overwhelmingly prioritizes technology over science.

What lessons might this history offer policymakers today?

There’s an emerging consensus in Washington, reflected in Sen. Schumer’s bill, that stimulating innovation requires spending more federal money on technology (rather than science) and distributing these funds geographically. Set aside the irony that the Endless Frontier Act is named after Bush’s report, while being based around these two pillars of Kilgore’s plan. It may well be time to give Kilgore a fair hearing — at least when it comes to geography.

The meritocratic system championed by Bush has resulted in federal funds remaining concentrated in a few regions of the country with prominent research institutions and a disparate share of high-paying jobs. This has bad economic and political consequences. But it may well be bad for science, too. Science tends to flourish in a pluralistic environment, not one dominated by entrenched institutions.

What about prioritizing applied research and development over basic science? This is not a new idea. We’ve been trying it for as long as the federal government has been funding research. If we really want to change course on U.S. R&D policy, we should follow Kilgore on geography, but Bush on basic science. That is, we should diversify federal funds geographically, while also prioritizing basic science. NSF would be a natural place to start.