In 2024, Nature published “The Economic Commitment of Climate Change,” by Kotz et al. (KLW24). A press release accompanying the paper’s publication announced that it projected enormous future GDP losses due to climate change, much more than almost all other studies:

Even if CO2 emissions were to be drastically cut down starting today, the world economy is already committed to an income reduction of 19% until 2050 due to climate change, a new study published in “Nature” finds. These damages are six times larger than the mitigation costs needed to limit global warming to two degrees.

The paper’s extreme results got a lot of attention — According to CarbonBrief, in all of 2024, KLW24 was the second most mentioned climate paper in the media.

Some went far beyond the paper’s claims. The Washington Post explained (incorrectly) that the paper showed why food prices were up last summer:

In March, a study from scientists at the European Central Bank and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research found that rising temperatures could add as much as 1.2 percentage points to annual global inflation by 2035. The effects are taking shape already: Drought in Europe is devastating olive harvests. Heavy rains and extreme heat in West Africa are causing cocoa plants to rot. Wildfires, floods and more frequent weather disasters are pushing insurance costs up, too.

Much more important than the media frenzy, KLW24 quickly found its way into important policy settings, including the U.S. Congressional Budget Office, the OECD, the World Bank, and the UK Office for Budget Responsibility.

Most importantly, the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), a consortium of more than 100 central banks from around the world, adopted the study’s results into a new official NGFS “damage function” to project the future costs of climate change, and thus shape how governments and businesses think about and respond to climate change.

Gregory Hopper, of the Bank Policy Institute (BPI), explains the outsized influence of the NGFS:

It is essential to recognize that the NGFS is not just another international organization or NGO. The NGFS is a forum for the world’s central banks and other regulators to agree on a common set of climate risk principles, even if they disagree with others, and also a workstream to develop a common climate toolkit that can be used for bank supervision of the climate risks of banks. Central banks and other regulators, including some of the world’s most important regulators, rely on NGFS output. Essentially, central banks and other regulators create the climate methodologies they use for bank supervision, but they present them through the NGFS.

Given its wide reach and impact, it seems obvious that the methodologies used by the NGFS should be accurate and unbiased.

We now know, however, that KLW24 and its application in policy by the NGFS and others are fatally flawed. Today, I discuss these flaws and their broader implications for climate research and policy.1

In a response to KLW24 published last week in Nature, Bearpark et al. (BHH25) showed that correcting inaccurate data from Uzbekistan in KLW24 reduces their estimate of projected 2100 damages due to climate change by about two thirds. This correction makes their damage estimates not statistically different from zero throughout the century. Making matters worse, these projections also employ the implausibly extreme RCP8.5 scenario.

On its own, BHH25 is devastating to KLW24. But that is just the start.

BPI’s Hopper has written a comprehensive critique of KLW24 – A Flawed Analysis With Massive Economic Consequences.2

Hopper’s analysis points out that the magnitude of Kotz et al.’s projected damage is driven largely by estimated effects of up to 10 years of lags in a variable that measures the annual change in temperature multiplied by the annual average temperature, where the estimated coefficients on these lags don’t decrease over time. In other words, KLW24 estimate that a year-to-year change in temperature has an equally large effect seven years later as it does in the present year. Adding these lagged effects up across years is what produces such large projected overall damages.

Hopper suggests that this seems so economically counterintuitive that it requires a very strong statistical justification to believe. Hopper concludes:

The statistical procedure used [in KLW24] to justify the new [NGFS] damage model is arbitrary and could easily have produced a damage function that would have predicted much smaller losses of global real income. Those much smaller loss projections should not be taken seriously either. In our assessment of the damage function, we found very limited statistical evidence for any causation between the climate variables and material economic damage and no statistical evidence for the purported influence of the temperature variables that drive almost all the economic damage.

Our findings are consistent with the current state of academic damage function research, which is highly uncertain at this point. One recent academic paper tested 800 plausible specifications of climate damage functions, finding that damages ranged from large economic benefits to large economic losses. With no academic consensus on climate damage functions, it is unclear why the NGFS would adopt the results of a single academic paper, especially given the massive ramifications for global economic growth.

Hopper says that he alerted the paper’s authors and journal editors of the problems he identified with the paper:

I sent the paper to the lead author and the Nature editors, even offered to submit a “Matters Arising” [comment] or whatever they wanted, but they never replied.

A similar critique to Hopper’s was published this week in Nature by Schötz, which concluded (emphasis added):

We find that their analysis underestimates uncertainty owing to large, unaccounted-for spatial correlations on the subnational level, rendering their results statistically insignificant when properly corrected. Thus, their study does not provide the robust empirical evidence needed to inform climate policy.

Serious problems with KLW24 were actually identified in the paper’s peer review process, but they were not addressed and the paper was published anyway.

One reviewer, near the end of the peer-review process, warned presciently:

I have a hard time in believing the results, which seem unintuitively large given damages aren’t perfectly persistent. . . Yet, it is worth probing further the possible sources of bias, because we know from the experience with Burke, Hsiang and Miguel (2015 in Nature) that publishing numbers in high-impact journals, which subsequently essentially get discredited,3 can create a lot of confusion.

Indeed. KLW24 was published in a high impact journal, with eye-popping numbers, has been adopted in many policy settings, and is now discredited.

For their part, the authors of KLW24 have written a new “do over” paper, published as a preprint, that introduces new data and new methods to arrive at results somewhat similar to those in the original paper. The new pre-print is a tacit admission by its authors that they have accepted that the original analysis no longer has merit. They needed to introduce new methods in the “do over” to arrive at similar results.

Hopper had a look at the new version of the analysis and is not impressed:

Changing to a specification of the model in response to a damning data error when that specification should have equally been included in the previous version, but was not, should engender serious skepticism about the methodology and results. Commenting in the Washington Post, Solomon Hsiang said: “Science doesn’t work by changing the setup of an experiment to get the answer you want. This approach is antithetical to science.” . . . The revised climate damage model is even more flawed than the original, since the statistical problems remain and it now appears that the model update was cherry-picked to reach a pre-determined conclusion.

Ouch.

It is worth noting that the timeline raises some serious questions.

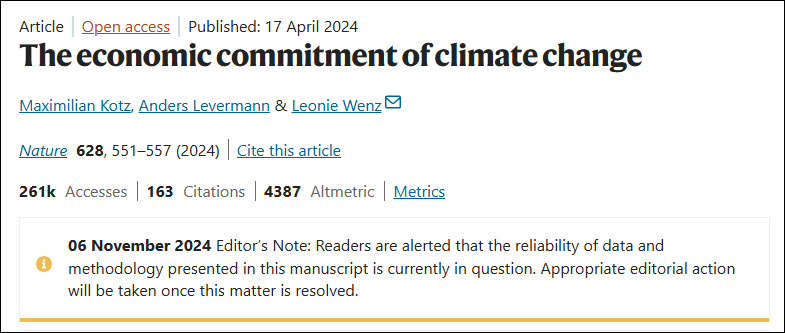

- KLW24 was published 17 April 2024.

- Schötz submitted his critique to Nature on 8 May 2024 and it was published 13 August 2025.4

- BHH25 submitted their critique on 16 September 2024 and it was published 6 August 2025.

- NGFS announced their new “damage function” on 8 November 2024, six months later, working closely with the authors of KLW24.

- Two days before that, on 6 November 2024, Nature added a public warning about the reliability of KWL24 (shown above).

- Hopper posted his critique of the NGFS “damage function” (which originated in KLW24) on 9 December 2024.

- The new preprint by by the authors of KLW24 — supposedy addressing the original paper’s errors — was posted 6 August 2025., just as Nature published the BHH25 and Schötz critiques.

Whatever the reality, it sure does look like Nature delayed publishing the critiques of KLW24 until its authors had a chance to prepare a new paper and post it as a preprint. For over a year Nature has had sufficient evidence, in my judgment, to retract KLW24 — which would have been a big domino to fall with significant consequences for climate policy. Instead, BHH25 and the KWL24 new “do over” preprint were published on the same day — an amazing coincidence.

KLW24 stands intact, along with the NGFS “damage function,” despite KLW24 being comprehensively discredited. Is it simply too big to fail?

Hopper asks some good questions:

[W]e do know that the Nature warning on the model was publicly posted on the article website and the NGFS did nothing in response. Shouldn’t the central bank members of the NGFS have asked Nature or Kotz et al. what the problem was? Shouldn’t the NGFS have retracted the model if they learned of the data error?

Taken together, BHH25, Schötz, Hopper, and the “do over” preprint make for a slam-dunk case for the retraction of KLW24. This should not have been a difficult decision for Nature.

Of course, as THB readers will appreciate, journal editors have judged that even the use of a fake hurricane dataset is not worthy of retraction in climate research! Knowing the right thing to do and then doing it is sometimes problematic in scientific publishing, especially when there are likely political ramifications.

More broadly, Hopper raises some additional important questions for the NGFS:

In November 2024, central banks and other regulators across the globe, under the auspices of the NGFS, put into their climate toolkit a climate damage function that could justify more stringent climate targets for banks, fines for banks that operate in Europe and potentially additional capital. About a month after the new damage function was released, a BPI study showed that the climate damage function had some serious statistical problems. It should not have been terribly surprising then to learn the climate damage function also had a serious data error that inflated its loss numbers by about a factor of three.

What is surprising is the reaction of the NGFS. The regulators in the NGFS could have, and should have, known about the data error before putting the new model into their climate scenario toolkit. They also could have investigated and acted when the academic paper the climate damage function was based on was called into question by the academic journal that published it. But they took no action and still take no action. . .

A general review and update of NGFS model control procedures is necessary to restore faith in their climate toolkit and data.

The more troubling questions remain unanswered: did any central bank or other regulator follow up with Nature or Kotz et al. when it was publicly revealed that there was a problem with the model they use to regulate banks? If they did not, why not? Are regulators putting their thumb on the scale, targeting a pre-determined conclusion rather than using the best scientific evidence?

In this case significant errors were made in an economic analysis, the peer review process broke down, media and policy analysts were far too credulous, and the flawed analysis has been adopted as gospel in policy guidance for banks and others managing the global financial system. It is no exaggeration that the errors in KLW24 may impact all of us, to the extent that NGFS guidelines influence the actions of financial institutions.

The scandal here is not simply that a flawed study made its way through peer-review — that happens.

The scandal here is that the paper’s errors have been understood for well over a year and yet the flawed paper continues to be relied on as the basis for important policy guidance. Nature has one job — to publish good science — and it has clearly failed in this case.

As we’ve documented before, climate science — in published research and as applied in policy — has a quality control problem that risks compromising public and policy maker trust in the entire field. Episodes like this compromise trust.

Mistakes happen. What matters more is what happens next. In climate science, self-correction is not always what comes next. It should.

1 Thanks to Matt Burgess and Gregory Hopper for helpful input as I prepared this analysis.

2 Hopper provides more details in four Substack posts: one, two, three, four.

3 This footnote is from RP — See Barker 2024

4 Hopper observes: “The data problem could have been confirmed quickly, in about a day or so, depending on computer speed. Verification requires a small code change to remove Uzbekistan from the regression dataset and then a re-estimation and re-simulation of the models.”