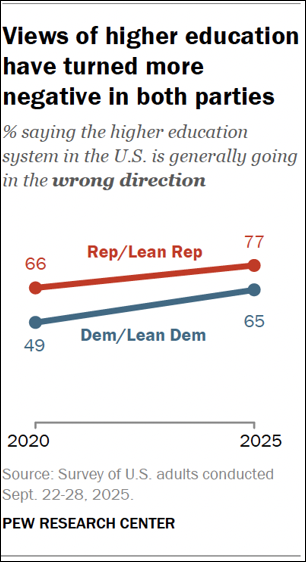

The bad news for U.S. universities keeps on coming. Last week, Pew Research released the results of a September 2025 poll showing that increasingly large majorities of Republicans and Democrats believe that the country’s higher education system is moving in the wrong direction.

In this broader context of public dissatisfaction with universities, the Trump Administration has offered nine universities an opportunity to sign on to a new “Compact for Academic Excellence in Higher Education” — with a deadline of today to agree to its terms, in order to continue to receive federal funding. So far, six of the nine universities have rejected the offer.

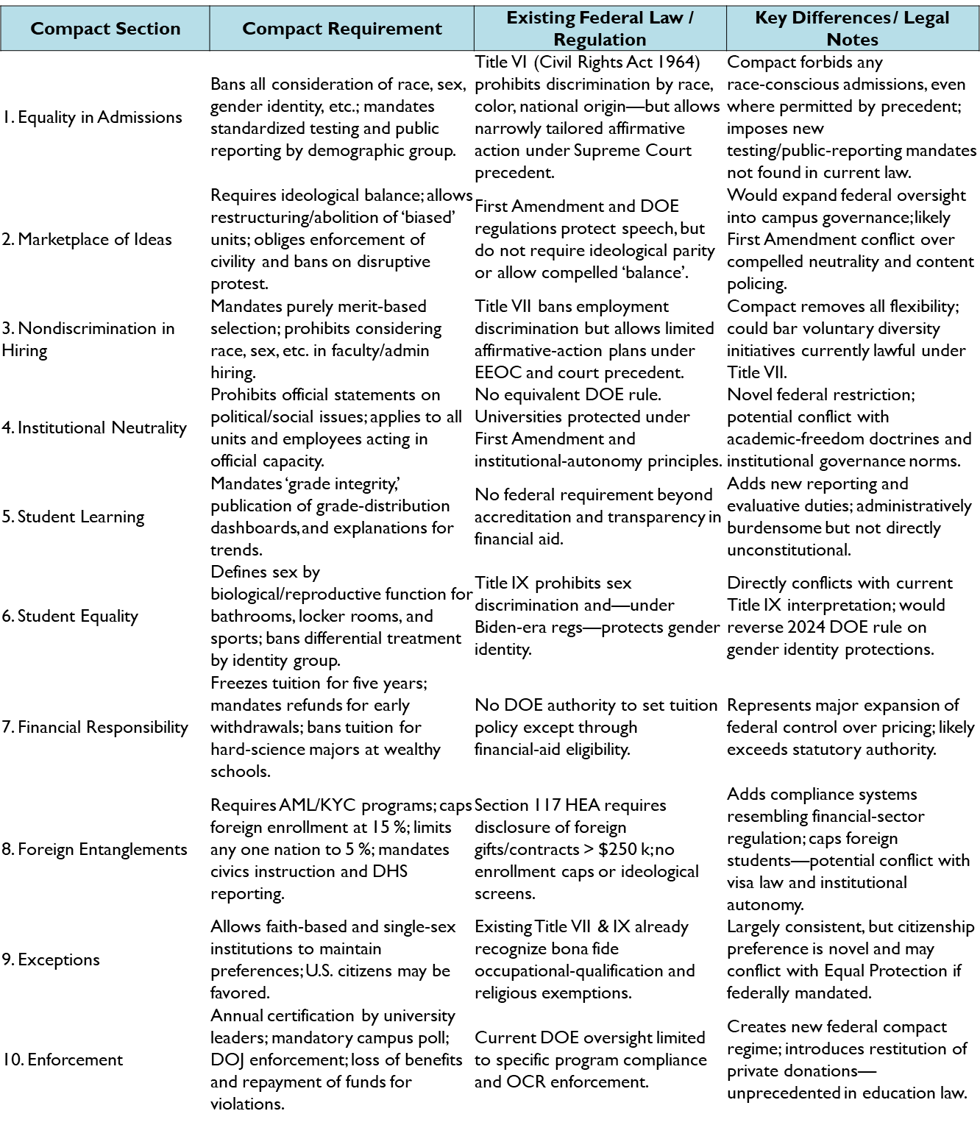

As there is plenty of discussion of the proposed Compact, much of it apparently unburdened by knowledge of what it actually says, I have enlisted my trusty research assistant ChatGPT to produce the summary table below, distilling the ten requirements of the Compact.

The Massachusetts Instituteof Technology (MIT) was the first institution to reject the Compact. MIT’s president, Sally Kornbluth, explained the decision in a letter to the Secretary of Education, Linda McMahon, noting that MIT already operates under a mission that shares many values in common with the proposed Compact.

At the same time, she noted that the Compact imposes unacceptable limits on academic freedom:

These values and other MIT practices meet or exceed many standards outlined in the document you sent. We freely choose these values because they’re right, and we live by them because they support our mission – work of immense value to the prosperity, competitiveness, health and security of the United States. And of course, MIT abides by the law.

The document also includes principles with which we disagree, including those that would restrict freedom of expression and our independence as an institution. And fundamentally, the premise of the document is inconsistent with our core belief that scientific funding should be based on scientific merit alone.

In our view, America’s leadership in science and innovation depends on independent thinking and open competition for excellence. In that free marketplace of ideas, the people of MIT gladly compete with the very best, without preferences. Therefore, with respect, we cannot support the proposed approach to addressing the issues facing higher education.

I agree with this stance — the proposed Compact includes some proposals that few would find objectionable and others that I cannot see any university leader accepting.

To get a sense of why it is problematic for a university to accept government oversight of its teaching and research, jump into a time machine with me to an alternate universe in spring 2029. Gavin Newsom has just been elected president in a landslide, bringing with him majorities in the House and the Senate.

His appointee to lead the Department of Education, Zohran Mamdami, has just announced an update to the government-university Compact — emphasizing preferential admissions for certain students, mandatory DEI programming, and a litmus test on research to ensure that it conforms with the administration’s policy goals in areas such as climate and wealth redistribution.

The U.S. does not need a new compact for higher education, because it already has one that has been in place for the past 80 years. As I’ve often argued (and lived as well), in recent decades universities have not held up their end of the social contract.

The existing contract needs to be repaired not jettisoned, which requires university-led reform, and not heavy-handed federal intervention. If universities want to operate with independence, then they must demonstrate that they can use that independence to fulfill their roles in serving all of society. The Trump administration should encourage internal reform and give universities the space they need to lead.

What is that longstanding social contract that I’ve been referring to?

Thirty years ago last month Rad Byerly (RIP) and I wrote an essay in Science that argued that the social contract established as post-World War 2 U.S. science policy was showing signs of strain.

We explained in The Changing Ecology of United States Science:

In this essay we address the “ecology of science” (1), that is, the relation of the world-leading institution of science in the United States-scientists, organizations, and culture-to its societal environment. Interaction between science and the rest of society has followed a paradigm, a social contract (2), codified in Vannevar Bush’s seminal 1945 report, “Science: The Endless Frontier” (3). The contract provided that in return for federal support and relative autonomy, “the researcher was obligated to produce and share knowledge freely to benefit-in mostly unspecified and long-term ways-the public good” (4, p. 4).

A major ecological function of the social contract is to shape the expectations of both science and society. Science expects autonomy and support. Society expects substantial benefits based on the justifications scientists offer for federal support.

Our 1995 diagnosis of strains on the social contract reads remarkably current in 2025:

Changes in the ecology of science may render the contract unsustainable; with the Cold War ended, science is adapted to an obsolete environment. Other environmental changes include (i) a dissatisfied public ready to reduce the federal government’s size and reach; (ii) deficit-reduction strains on funding, leading to many program reductions; (iii) increasing public awareness of problems that neither science nor government has resolved, including racism, drug abuse, breakdown of community, and crime; and (iv) two decades of decay in real wages, leading to politics focused on the grievances of the middle class. Science competes for funds that otherwise might address such problems directly. Problem resolution will become increasingly important in justifying support for science. Legislatures challenge research universities to contribute more to society, to better educate undergraduates, and to study practical problems.

We explained that Vannevar Bush’s social contract rested upon three key assumptions:

First, scientific progress is essential to the national welfare. Bush formally avoided promising too much by noting that science “by itself, provides no panacea for individual, social, and economic ills,” but instead serves the national welfare “as a member of a team” (3, p. 11). In practice, however, science and society soon forgot this disclaimer and assumed that benefits would automatically follow research.

The second assumption is that science provides a reservoir of knowledge that can be applied to national needs (3, p. 12). The image of flow into a fund or reservoir is another critical metaphor of the report. “Basic research . . . provides scientific capital. It creates the fund from which the practical applications of knowledge must be drawn” (3, p. 19). Implicit in the reservoir-flow metaphor is a linear model of the relation between science and society in which social benefits occur “downstream” from the reservoir of knowledge.

The third assumption is that “scientific progress on a broad front results from the free play of free intellects, working on subjects of their own choice, in the manner dictated by their curiosity” (3, p. 12). For knowledge to flow freely, science must proceed unfettered by political or other constraints. Bush argued that because scientists can best judge science, the direction of research should be their responsibility. The reservoir isolates science from society, keeping it “pure.” On the basis of these assumptions “science is a proper concern of government” (3, p. 11) and “federal funds should be made available” (3, p. 31); that is, government should sustain the “wellspring” of knowledge.

For almost fifty years, the Cold War provided a backdrop to U.S. science policy and a compelling justification for university-based research funded by the government. The Cold War would be won through advances science and technology and universities were absolutely central to those advances. The political justification did not really even need to be made, which is a major reason why federal funding for extramural federally-funded R&D enjoyed strong bipartisan support for generations.

With the end of the Soviet Union that overriding justification for federal funding of universities disappeared in an instant. Universities were unprepared, and arguably have been struggling ever since with finding purpose in the aftermath of the Cold War.

We argued that the scientific community needed to be more accountable to societal needs and to avoid elitist isolation:

To be sustainable, science must meet two related external conditions: (i) democratic accountability, including accountability to societal goals (17), and (ii) sustained political support. (Of course, science must meet its own internal standards.)

Under democratic accountability, science is consciously guided by society’s goals rather than scientific serendipity. Good science is necessary but not sufficient; association with a societal goal is required. The Bush paradigm discourages explicit association with goals that are not those of science. Social accountability leaves to scientists a broad scope of scientific choice. Denial of accountability encourages elitist isolation.

Improved justifications will sustain political support for science because support is strengthened by performance commensurate with expectations (18), and expectations of science are a function of justifications made in the process of securing funding. By assuming the automatic generation of benefits, Bush’s social contract precludes realistic expectations of science, implying that science can solve some problems that, in fact, alone it cannot. Reliance on an outdated social contract leads to a loss of faith in science and a subsequent loss of political support.

One way to view the predicament that elite universities currently find themselves in is that in the decades since the end of the Cold War professors, administrators, and scientists have increasingly focused on serving the interests of a subset of America, and have designed universities to serve that narrowing focus.

As has been documented extensively, universities have become captured by the political left and have taken on institutional stances that are actively in opposition to those on the right and (especially) centrists.

It is no wonder that increasing shares of the population see universities as moving in the wrong direction. The Trump administration’s response is wrongheaded to be sure, but their diagnosis of a problem is not entirely wrong. [1]

Our 1995 recommendation for a path forward still makes sense in 2025, and is arguably ore timely than ever:

To achieve the vision [of a renegotiated social contract], we recommend a national debate on the future of science, eschewing defense of the status quo and putting aside current budget issues. The debate should address, with empirical evidence, the following two questions: (i) In what ways does science contribute to the national welfare? and (ii) How can science best be marshaled to assist in addressing specific societal problems? Because science affects all of society, debate should not be limited to scientists. Each forum should give equal voice to informed outsiders, seeking and answering sober critics, and welcoming growth in perspective. The academies and professional societies should lead the debates; Congress, universities, laboratories, industry, nongovernmental organizations, and individuals should participate.

Universities should say no to President Trump’s Compact, but they should at the same time say yes to reform from within.

Read more about universities and how they got where they are in the THB Series Politicization of the American University:

- Part 1 —The Problem

- Part 2 — Partisan Professors

- Part 3 — How Universities Went Off Track

- Part 4 — How to Get Rid of a Tenured Professor

- Part 5 — Fixing Universities

[1] I note with some wry humor that the University of Colorado Boulder has just advertised my former faculty position, and the job announcement includes language suggestive of a political litmus test for applicants focused on climate policy — calling for applicants committed to “sustainability and decarbonization.”