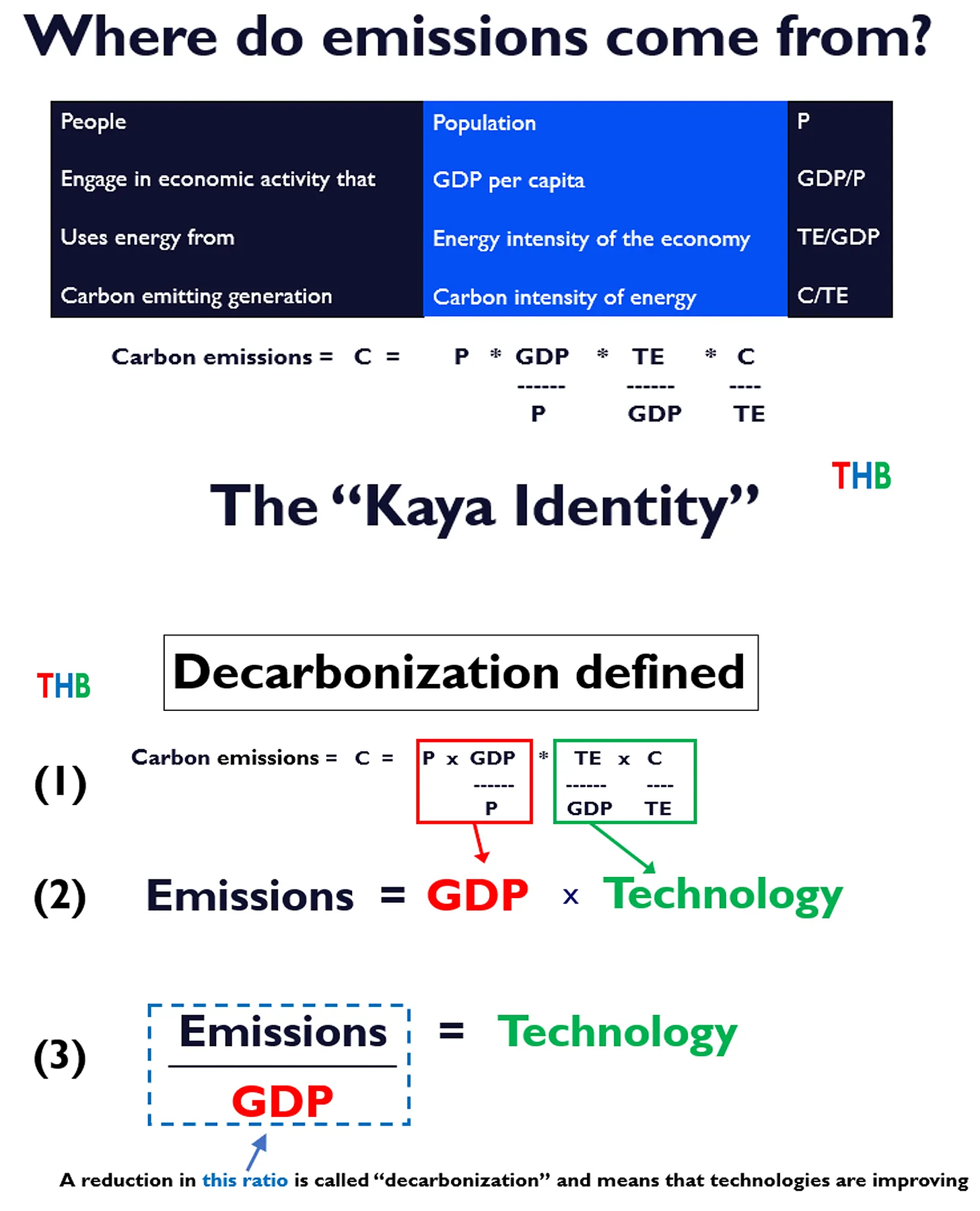

Last month here at THB, I used the “Kaya Identity” to explain the concept of decarbonization, which refers to a reduction in the ratio of carbon dioxide emissions to GDP. I showed data at the global level, which indicates that the world as a whole not only remains far off the pace of decarbonization that would be consistent with the Paris Agreement targets, but that there is little evidence that climate policy is having any discernible effect on decarbonization at the global scale.

The Kaya Identity and decarbonization are defined in the image below. A reduction in the ratio of carbon dioxide emissions to GDP indicates progress in the deployment of technologies of energy consumption and production.

Today I share a deeper dive into decarbonization, looking at specific countries.1 Here is my methodology:

- Data on carbon dioxide emissions from energy 1990 to 2022 is from the Energy Institute Statistical Review of World Energy 2023.

- GDP data (PPP) comes from the World Bank.

- I focus on the top 20 emitters in 2022, who together represent ~83% of global carbon dioxide emissions from energy and ~72% of global GDP.2

- I calculate annual rates of decarbonization from 1992, when the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change (FCCC) was introduced at the Rio Earth Summit, and from 2015, when the Paris Agreement was adopted.

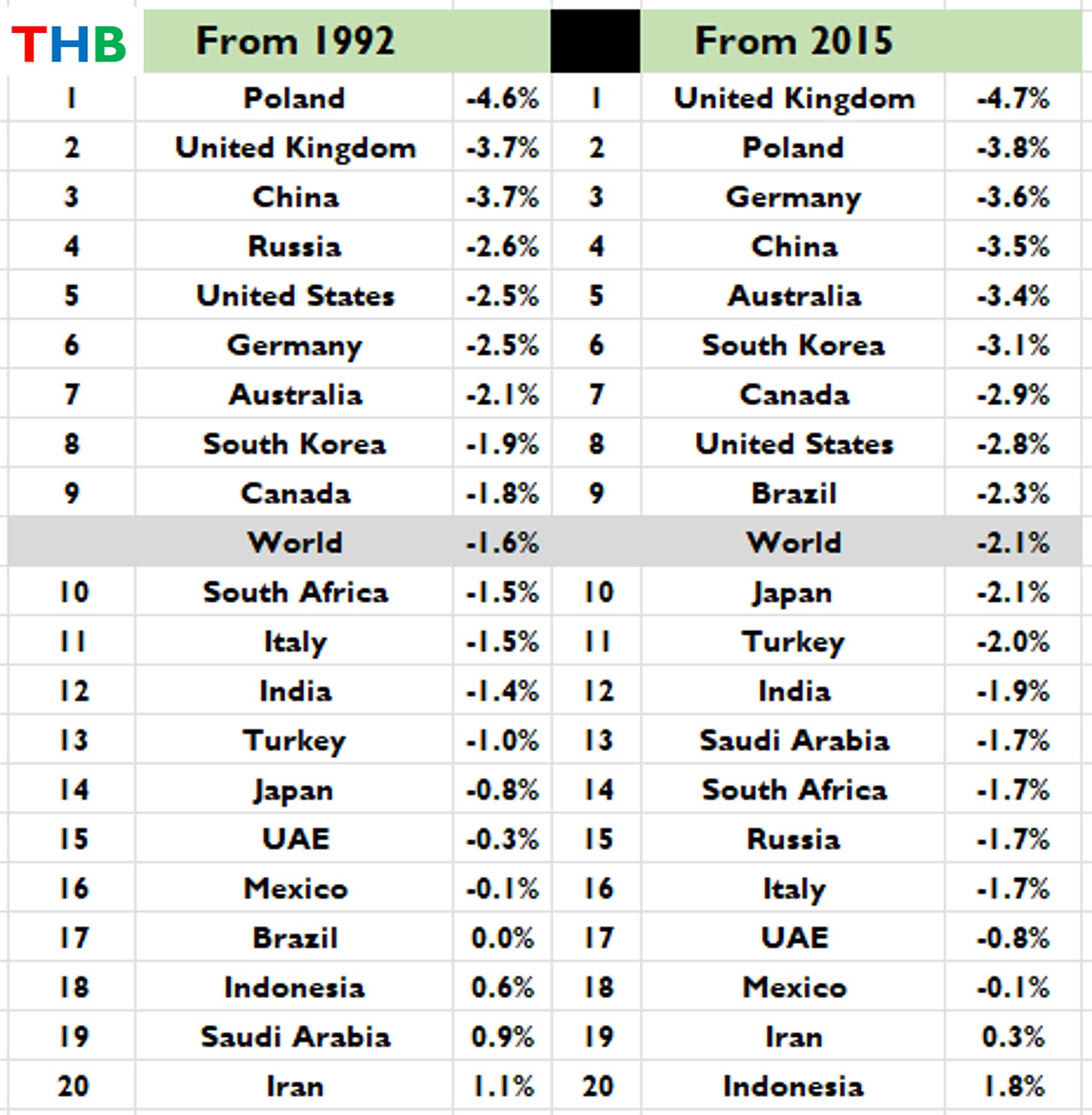

Below are the tables showing decarbonization rates over these two periods for the 20 countries.

Poland — a surprise to me — occupies the top of the table for 1992 to 2022 and sits at second place since the adoption of the Paris Agreement. Nine of the 20 countries exceed the global average rate of decarbonization in each period, with Brazil replacing Russia in the more recent period since the Paris Agreement. Since adoption of the Paris Agreement, two of these 20 countries are not decarbonizing at all, and instead their economies have become more carbon intensive — Iran and Indonesia.

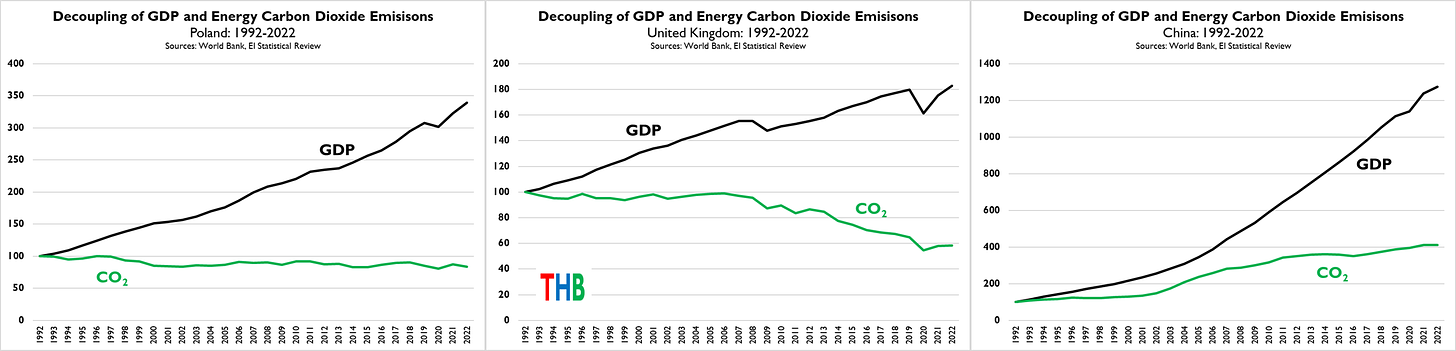

We can get a better sense of what is going on in individual countries by examining emissions and GDP separately, as shown in the figure below for Poland, the United Kingdom, and China. Note that each figure has a different vertical axis range.

From these graphs we can see that:

- Poland’s high rate of decarbonization is a result of its strong economic growth accompanied by a slight decline in emissions, more than tripling its economy with no increase in emissions.

- The UK’s higher rate of decarbonization was due to a large (~40%) reduction in emissions since 2007 (due to the 2008 Climate Change Act? Brexit?). The UK would have a significantly higher rate of decarbonization with greater economic growth, which trails far behind Poland and far, far behind China — Although that would raise the question whether higher economic growth would have required greater emissions.

- China’s high rate of decarbonization was due to a rate of economic growth that far exceeded its growth in emissions, at a rate of more than 3 to 1.3

No country has achieved rates of decarbonization remotely consistent with the targets of the Paris Agreement, such as net-zero by 2050. To meet aggressive targets for deep decarbonization requires very high rates of decarbonization — Consider that achieving an 80% reduction in global emissions by 2050 implies a rate of decarbonization from ~7% to ~9% per year, for annual global economic growth of 2% or 3%. That is basically a quadrupling of the rate of global decarbonization since the adoption of the Paris Agreement.4

The data shared above does not allow for identifying the possible effects of climate policies on rates of decarbonization, however this dataset will allow us to explore this issue. That will be the subject of a future post.

This analysis is based on methods that I discuss in depth in The Climate Fix, which is available as a PDF here to THB paid subscribers. A focus on decarbonization offers the most straightforward approach to evaluating the effects of climate policies focused on meeting emissions targets.

This is a post from Roger’s Substack, The Honest Broker. Please consider subscribing here.