On Tuesday this week the U.S.-China Science and Technology Agreement (STA) is due to expire unless the U.S. and China can agree on its extension. Today I provide some background on the agreement, why it is now being debated, and my view on what should happen next.

STAs are a common tool of science diplomacy. The U.S. has more than 60 STAs with countries around the world, overseen by the State Department, which explains:

These agreements, and their associated expert meetings, strengthen international cooperation in scientific areas aligned with American interests, ensure open data practices, promote reciprocity, extend U.S. norms and principles, and protect American intellectual property.

We recognize that not every country shares American values – in fact, some attempt to illicitly acquire America’s intellectual property and proprietary information. As such, STC works with foreign allies and federally funded scientists to ensure the United States rightfully reaps the benefits of international science and technology cooperation and that those with whom we cooperate adhere to the rules-based order. STC monitors worldwide trends in science and technology to retain U.S. advantages over strategic competitors and improve our understanding of how they may influence—or undermine—American strategies and programs.

According to a 2021 study, at that time China had 52 STAs and 64 other cooperative agreements with countries around the world. “Science diplomacy” is low hanging diplomatic fruit for both the U.S. and for China.

The U.S.-China STA was first signed in 1979 and originally emphasized agricultural research and development. The STA was the first agreement between the countries following the normalization of relations in January of that year.

Over the decades that followed, the agreement was renewed every five years, most recently in 2018, with the scope of cooperation generally expanding. In 2023, when the STA was again due to be renewed, the U.S. and China agreed only to a six month extension, in order to re-negotiate its provisions, and in March, 2024 another six-month extension was agreed — which expires tomorrow.

The agreement reflects a longstanding U.S. policy of engagement with China on science and technology. Historically, science diplomacy has been seen as an opportune way for countries — even adversaries and competitors — to collaborate and connect.

The Congressional Research Service explains how the U.S. viewed the agreement through the Obama administration:

The STA was a part of U.S. strategy at the time to build ties with China to counter the influence of the Soviet Union. During the 1980s and 1990s, U.S. strategy shifted and science and technology (S&T) ties became part of a broader U.S. effort to integrate China into the global system and influence its development trajectory and behavior. President Barack Obama expanded S&T ties with China to address global challenges, such as health, energy, and climate.

Under the Trump administration, the U.S. shifted towards a stance of “decoupling” from China — defined as efforts to separate the world’s two largest economies. The Biden administration has continued with a similar stance. It is unclear what position a potential Harris administration might take — In Washington, DC, “decoupling” has bipartisan support, but it also has bipartisan opposition.

Setting aside the wisdom or practicality of decoupling, it is the political context in which the STA is being reconsidered and renegotiated, and explains why the U.S.-China STA — after more than 45 years — is now the subject of debate.(1)

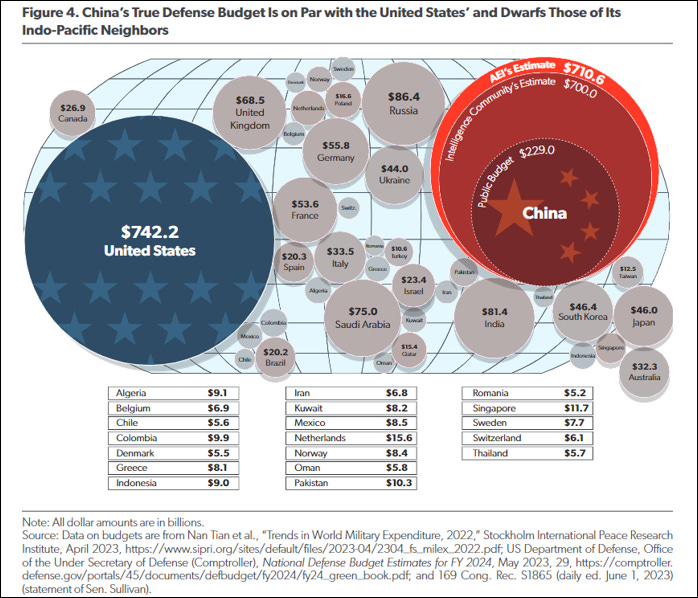

Back in 1979, China’s economy was one tenth the size of the U.S. economy and its role in global research and development was exceedingly small. Today, China’s GDP is more than $18 trillion, trailing only the U.S. at more than $27 trillion. China is today a research and development powerhouse. In addition, China’s spending on defense is of a similar magnitude to that of the U.S., according to an AEI report earlier this year.

In U.S.-China relations, Taiwan is a central issue, which happens to produce “60 percent of the world’s semiconductor chips, a large percentage of which are highly advanced.” China is seeking to “catch up” on the technology and production of semiconductors and surpass its competitors on technology more broadly — part of Xi Jinping’s “pledge to mobilize all means at [China’s] disposal to wrest technological supremacy from the United States and other nations.”

It is easy then to see how the U.S.-China STA has morphed from a matter of science diplomacy to much higher stakes diplomacy.

Yesterday, the Financial Times reported on recent diplomatic efforts between the two nations that appear to have resulted in a thawing in relations. Sources characterized China’s top two priorities in the discussions as: “the intersection of economics, technology and security, and secondly Taiwan.”

A U.S. official characterized the discussions in terms of the countries’ different views on technology and technology transfer:

“Tech is a massive priority for them [China]. They do not accept the underlying premise of what they see as essentially the securitisation of the technology relationship when they view it as fundamentally about core economics and innovation and not about national security.”

A science and technology agreement is not a treaty requiring Senate ratification, but some in Congress have expressed an interest in much greater oversight of the agreement. The Congressional Research Service has presented — in an excellent example of honest brokering — seven non-exclusive options for the future of the STA:

- (a) renew the U.S.-China STA as is;

- (b) renew the STA and modify sub-agreements;

- (c) modify and renew the STA;

- (d) significantly rework and renegotiate the STA;

- (e) let the STA expire;

- (f) shift focus to deepen STAs with Europe, Japan, and others; and

- (g) work with allies and partners to develop a common approach to S&T work and with regard to China.

One big issue that is not being discussed (at least in public) — which we might call the panda in the room — is the origins of COVID-19 and what, if any, role the U.S.-China STA may have played in U.S. funding of, oversight (or lack thereof), or scientific collaboration in risky research on diseases. Risky pandemic research, and more generally “dual use” research and development, is exactly the sort of thing that Congress should be overseeing with much more focus and attention.

“Jaw, jaw is better than war, war.” —Winston Churchill(2)

So what should the U.S. and China do?

They should work to renegotiate the STA and not stop until they succeed.

There are some easier parts — such as, “exchange of scientists, scholars, specialists, and students; exchange of scientific, scholarly, and technological information; joint projects; joint research; and joint courses, conferences, and symposia.” If during the height of the Cold War the U.S. was able to successfully engage the Soviet Union on issues of science and technology, then it can certainly do so with China in 2024.

There are of course many complexities to be worked out over issues related to technology transfer, industrial competition and collaboration, intellectual property, trade, and more. These issues are well above the pay grade of the scientific community and will require the engagement of each nations’ leaders. This is challenging and difficult diplomatic work in normal times and is even more challenging in the bright spotlight of contested U.S. views on engagement with China.3

For my part, I support continuing the U.S.-China STA in the most robust form that can be negotiated between the two nations. In my view, its existence is much more important than the exact particulars. In general — and contrary to both Trump and Biden — I view “decoupling” to be a bad idea and it is also a bad idea in science and technology.

Ideally, the Biden administration will successfully negotiate a new five-year agreement and not another six-month extension. We should expect that there are some in Trump’s orbit who would want to just can the agreement — a horrible idea. The STA offers a timely topic for the Harris campaign to begin to articulate a muscular but practical approach to collaboration with China on issues of science and technology.

This post was originally published on Roger’s Substack, The Honest Broker. If you enjoyed the piece, please consider subscribing here.

Interestingly, even under its stance of “decoupling” the Trump administration did not cancel or even discuss (to my knowledge) the U.S.-China STA during its four years. It may be that Trump’s political appointees were not aware of it or were uninterested. Given that the attention of Congress is now on the agreement, it would be unlikely to go unnoticed in a second Trump administration.

According to Churchill’s biographer, Sir Martin Gilbert, Churchill actually said “Meeting jaw to jaw is better than war.”

A recent German government report on German-China collaboration on science and technology recommends a realpolitik approach.