The implausibly extreme and hugely popular climate scenario RCP8.5 made it into President Trump’s executive order last week on “Restoring Gold Standard Science.” Ironically, the Trump administration’s characterization of RCP8.5 did not quite reach the “gold standard,” and maybe not even a “bronze standard. “

The EO states:

[Federal a]gencies have used Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) scenario 8.5 to assess the potential effects of climate change in a “higher” warming scenario. RCP 8.5 is a worst-case scenario based on highly unlikely assumptions like end-of-century coal use exceeding estimates of recoverable coal reserves. Scientists have warned that presenting RCP 8.5 as a likely outcome is misleading.

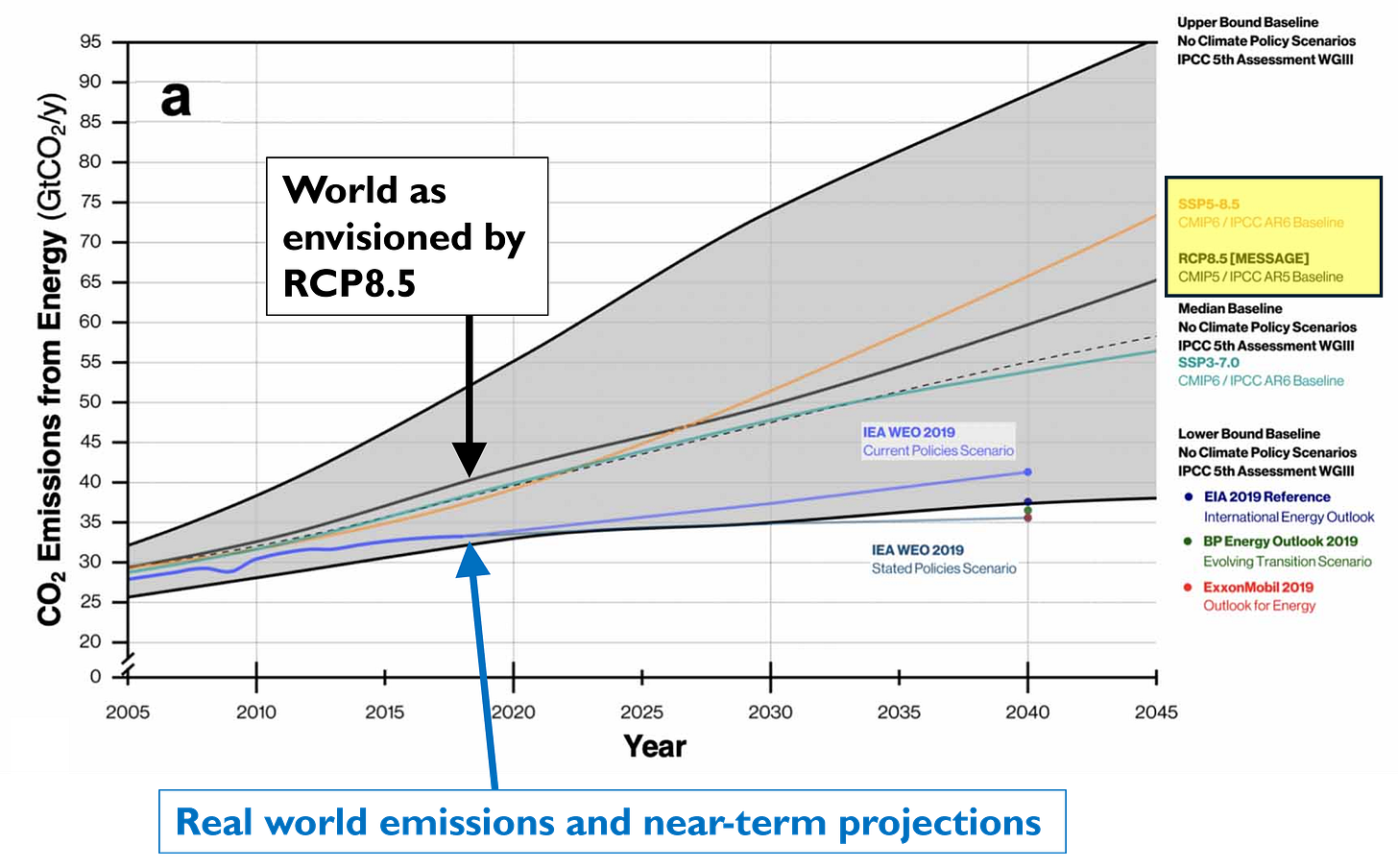

RCP8.5 is not simply “highly unlikely” — it is falsified, meaning that its emissions trajectory is already well out of step with reality. We showed this conclusively in Burgess et al. 2021, from which the annotated figure below comes from.

The gap between the black arrow (RCP8.5) and the blue arrow (reality) indicates that RCP8.5 is not just unlikely, but impossible — it is already wildly wrong. Since we published that paper, that gap between RCP8.5 and reality has only grown larger (stay tuned on that!).

It is an interesting thought experiment to ask what it would take for the real world to “catch up” to RCP8.5. Setting aside the real-world plausibility of such a “catch-up” scenario, as a matter of simple math, starting in 2025 that new scenario would have to be much more aggressive than RCP8.5, and thus even more extreme. If RCP8.5 is implausible, then a new, catch-up-to-RCP8.5 scenario would necessarily be even more implausible.

Climate scientist Zeke Hausfather dismissed the Trump administration’s claims about RCP8.5, by stating that the research community has moved on, and in the process he was no doubt sub-Tweeting THB (which under no circumstances is to be engaged directly!):

Its bizarre, particularly coming after there has been a real shift in [RCP8.5] use post-AR6 due to recognition of the changing likelihoods of high emissions scenarios. Its almost like science is self-correcting.

Zeke’s nothing-to-see-here is wrong. The IPCC AR6 came out in 2021. From 2018 to 2021, Google Scholar reports 17,000 articles published using RCP8.5. From 2022 to 2025, Google Scholar reports 16,900 articles published using RCP8.5. Some shift.

The Trump administration’s characterization of RCP8.5 is not quite right, but its focus on its continued misuse is also not wrong.

With RCP8.5 out-of-date and implausible, it raises an important question: What then is a “worst case” climate scenario for use in policy?

In discussing this with colleagues, reading a bazillion RCP8.5 papers, and chatting with AI models trained on such information, I’ve come to the conclusion that a very common definition of “worst case scenario” is simply circular: The most extreme scenario developed by the IPCC-affiliated scenario community and made available for research purposes.

In labeling a scenario as “worst case” the climate community has never made a systematic, scientific effort to assess either plausibility or, at the other extreme, whether there might be even more extreme scenarios that might be plausibly “worser.”

Worst case scenarios are important for policy and planning because they allow for stress testing of proposed and enacted decisions against low probability but plausible outcomes that policy makers might wish to consider in robust policy making, resilient to a highly uncertain future. However, consideration of an impossible or extremely improbable scenario could lead to wasted effort, misplaced resources, and poorly-informed decision making.

Careful consideration of worst-case scenarios is thus crucially important and must mean more than simply — the most extreme scenario I have at my disposal.

In 2009, climate scientist Steve Schneider wrote an essay in Nature describing a “worst case scenario” with a 2100 carbon dioxide concentrations of 1000 parts-per-million (ppm) and approaching a temperature increase of 7 degrees Celsius. Schneider’s “worst case” was even more extreme than RCP8.5 — which had yet to enter the scene — and seemed to be based on the fact that 1000 is a nice round number, close to the most extreme scearnio then available (A1FI).

But why stop at 1000 ppm and 7C by 2100? Surely 1500 ppm and 10C would be much worse? I could go on, inventing ever-more-worser scenarios. But this exercise would obviously be useless from the perspective of reliably informing decision making.

Then there is also the matter of “worse” with respect to what? As Mike Hulme has argued:

“[T]here are some futures beyond 1.5 degrees C (or even 2 degrees C) that are more desirable than other futures which do not exceed these warming thresholds. We should not mistake one set for the other.”

Is a worst case climate scenario defined by temperatures alone or, alternatively, human outcomes like health, wealth, equity, and so on? Who gets to decide?

Consider that RCP8.5 has large temperature increases, but in a world that is assumed to be fantastically wealthy. Is that a better or worse case than a scenario with massive global poverty and inequity but much lower change in temperatures?

It turns out that defining a “worst case scenario” is not a bloodless technical exercise, but a deeply value-laden process that must recognize that different people will value different outcomes differently. That makes the characterization of a “worst case outcome” inevitably political, and the product of discussion, disagreement, debate, and negotiation. There are many legitimate perspectives on what constitutes “worst case.”

Politics enters such an exercise in other ways as well. With respect to projected temperature changes, climate advocates will want to legitimize the most extreme scenario they can, thus bringing extreme outcomes into the policy discussion — one explanation for the staying power of RCP8.5. At the same time, those opposed to action on climate will want to exclude as many extreme outcomes as possible, thus restricting discussion of plausible futures to those much more benign. These differing persepctives inevitably get mixed up with technical discussions of sceanrio plausibility.

Remarkably, there is almost no critical discussion of “worst case scenarios” in climate science or policy. Nor is there acknowledgement of the inherent political nature of such discussions. Instead, the “worst case scenario” is simply the one that a small group of climate cientists assemble for purposes of climate modeling, and then shows up in scenario databases, ready to be plugged into the next study and shape important discussions about policy.

Definition of a “worst case” scenario (or scenarios) for policy planning should not come from a directive from the Trump (or any) administration. Equally, they should not come from a narrowly empaneled group of scientific or technical experts. The broader community — including experts, policy makers, stakeholders, citizens — needs to take more seriously the political dimensions of scenario planning for climate policy, and create institutions and processes that keep scenarios up-to-date and societally legitimate.

The political importance associated with climate scenarios means that those holding a tight grip on their creation today will be unlikely to open up that process to a more democratic approach to thinking about our collective futures and the different paths ahead.

This post was originally published on The Honest Broker. If you enjoyed this piece, please consider subscribing here.