Last week, I testified before the Senate Committee on the Budget in a hearing titled, Droughts, Dollars, and Decisions: Water Scarcity in a Changing Climate.1 The hearing was the 18th in the Committee’s series on climate change this Congress, prompting the Wall Street Journal to suggest “the old-fashioned idea that the Budget Committee ought to focus on the budget.”

The hearing could easily have been held the Senate Agriculture Committee, and indeed, almost all the questions from senators to the witnesses came from Budget Committee members who are also on the Agriculture Committee.

I was invited to testify on what the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) says about drought — and I focused my testimony on the finding of the IPCC Sixth Assessment (AR6) Working Group 1 (WG1). I always appreciate the opportunity to testify before Congress, and I thank Senators Whitehouse and Grassley for the opportunity.2

Aside from my testimony, there was essentially no discussion of climate change — it was mostly about local farming and urban water management, both crucially important. All the witnesses were excellent, and the Senators asked some worthwhile questions.

Some tidbits I left with from the other witnesses:

- Despite a large increase in population, Southern California has cut its water consumption by about half since the 1970s.

- Almost all of the world’s carrot seeds are produced in the high desert of Oregon.

- Despite variability and changes in U.S. climate, agricultural productivity has continued to increase, and with no end in sight.

My testimony focused on summarizing what the IPCC AR6 Working Group 1 said about drought, with a focus on the United States (specifically, North America).

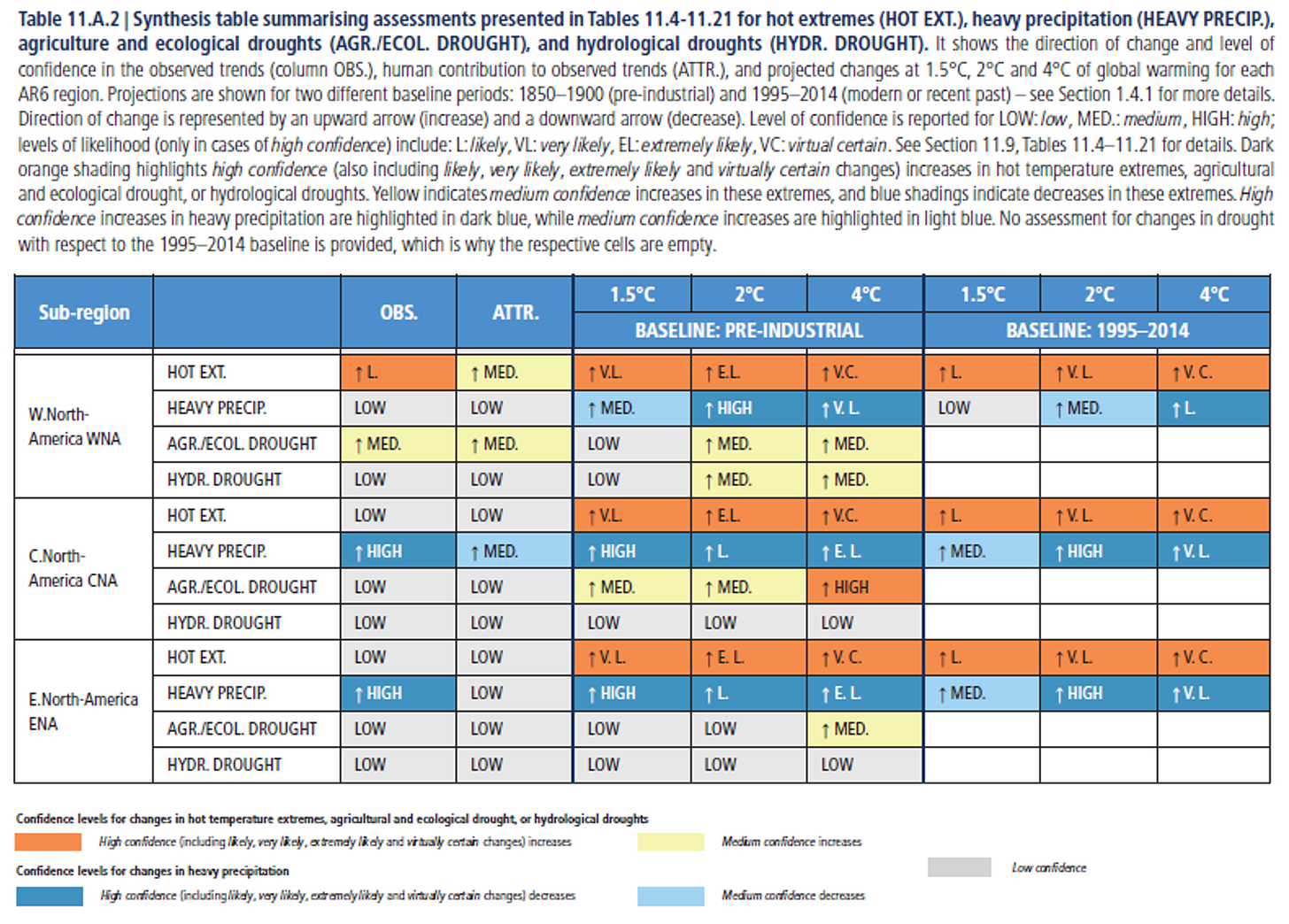

The image above, a screenshot from the IPCC AR6, is worth looking at closely. It shows:

- Low confidence (2 in 10) in detection of changes in drought across the U.S., with the exception of increasing “agricultural and economical drought” in Western North America at medium confidence (5 in 10).

- No ability to express any confidence in how drought may change from a 1995 to 2014 baseline under future temperature changes of >1.5C from that baseline (Note: a 1.5C change from that recent baseline is about the same as a 2.5C change from preindustrial, which is similar to a “current policies” baseline and well below a SSP2-4.5 scenario).3

In fact, the IPCC has not achieved detection of trends in drought anywhere in the world at a level consistent with the IPCC’s threshold for detection (i.e., at least very high confidence or 9 in 10). The IPCC has detected an increase in hydrological drought in the Mediterranean and North East South America with high confidence (8 in 10) but has, respectively, only medium confidence and low confidence in attribution in those two regions (5 in 10 and 2 in 10).

The IPCC does conclude with high confidence that human-caused climate change affects the hydrological cycle, and thus drought. However, achieving detection and attribution of trends in the IPCC’s various definitions of drought — both observed and projected — in the context of significant internal variability remains a challenge.

Don’t take it from me. Here is what the IPCC AR6 concluded:

There is low confidence in the emergence of drought frequency in observations, for any type of drought, in all regions. Even though significant drought trends are observed in several regions with at least medium confidence (Sections 11.6 and 12.4), agricultural and ecological drought indices have interannual variability that dominates trends, as can be seen from their time series (medium confidence)

In fact, published studies are lacking that explore when signals of projected changes in drought might emerge from the background of internal climate variability, under the IPCC’s framework for detection and attribution:

Studies of the emergence of drought with systematic comparisons between trends and variability of indices are lacking, precluding a comprehensive assessment of future drought emergence.

Given the closing “jaws of the snake” due to the growing recognition of the implausibility of extreme climate scenarios, it will be interesting to see what future “time of emergence” studies say about projected changes in drought. I’ll have a post dedicated to this neglected topic in the coming weeks.

As I said at the hearing, it is easy to perform anecdotal attribution of any weather and climate event that happens anywhere on the planet (Turbulence! Home runs! Migraines!). The IPCC tells us that reality is just a bit more complicated.

Climate change is real and important, of course, but reducing the causality of everything to climate change flattens our understandings and distracts from more detailed explorations of the proximate cause of events, which are always far more important for thinking through policy alternatives.

My oral remarks are reproduced below and you can find my full written testimony here in PDF. A full video of the hearing can be found here. In the coming weeks, I’ll have a post dedicated to my written testimony.

1 You can read my views on testifying before Congress here.

2 I was invited by Republicans. In the past I was invited by Democrats. I’ve always been a registered Independent in the state of Colorado. Read more here.

3 The IPCC’s two baselines — preindustrial and recent — has me thinking about practically relevant detection and attribution. Expect a post on this soon!