In an op-ed yesterday in the Wall Street Journal, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), announced that he was sacking all of its members of “to re-establish public confidence in vaccine science.”

He explained:

[W]e are taking a bold step in restoring public trust by totally reconstituting the Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices (ACIP). We are retiring the 17 current members of the committee, some of whom were last-minute appointees of the Biden administration.

In a HHS press release, Kennedy explained further:

The Biden administration appointed all of the 17 sitting ACIP members. Thirteen of them were appointed in 2024. These appointments would have prevented the current administration from choosing a majority of the committee until 2028.

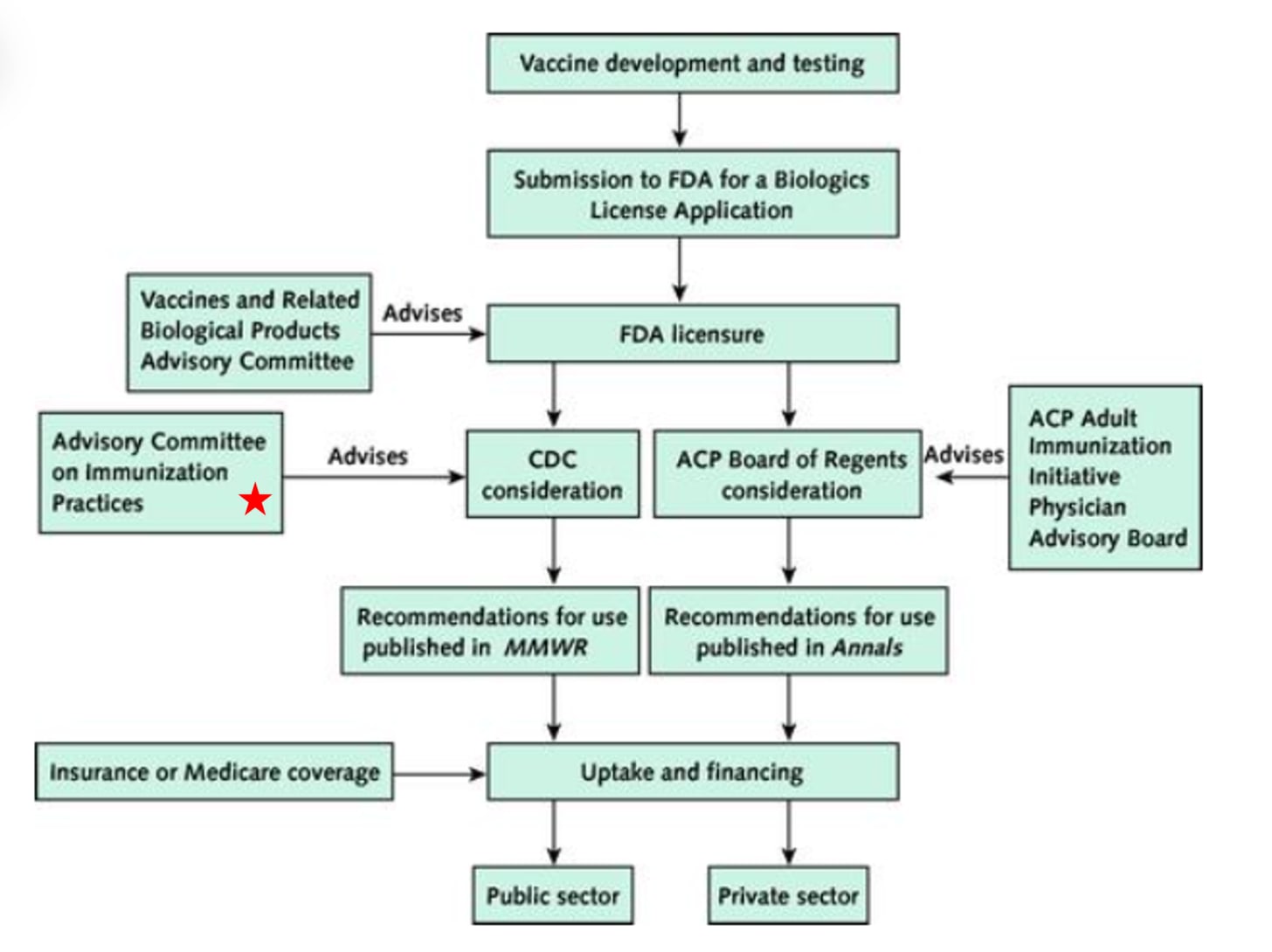

The sacked experts were members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), which was established by Congress in 1964 to advise the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) on vaccines and vaccination. The ACIP provides advice, it does not make decisions, although its advice is typically followed.

The figure below shows where the ACIP sits in the U.S. government’s vaccine approval process — I added the red star. The ACIP is just one of several expert advisory bodies that provide recommendations to policy makers related to vaccines.1

Today, I take a look at the asserted problem: “a crisis of public trust” — and the asserted remedy: “A clean sweep [of ACIP] is necessary to reestablish public confidence in vaccine science.” Both are problematic and signal much deeper challenges for securing expert advice that is authoritative and legitimate — in public health and beyond.

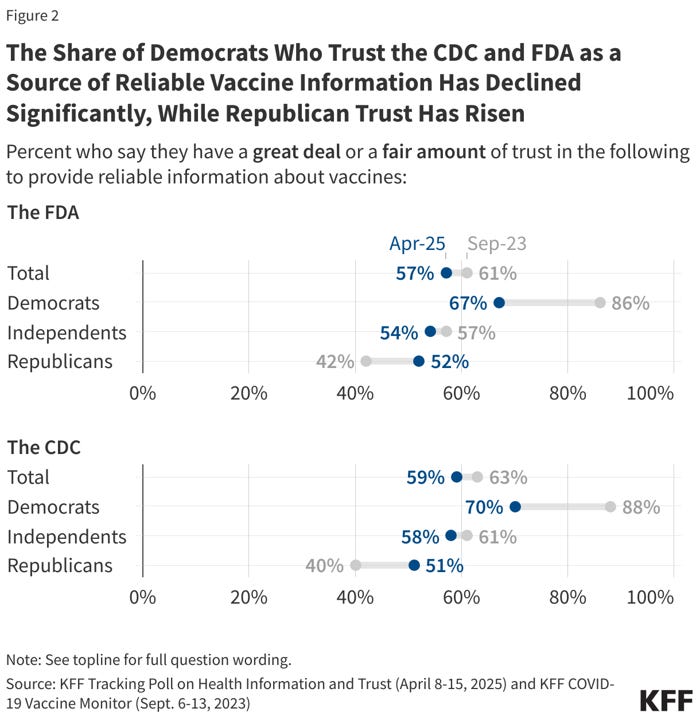

According to the KFF Tracking Poll on Health Information and Trust, most recently updated last month, there has indeed been a decline in public trust in the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the CDC. However, the polling reveals a sharp partisan split since 2023, with trust plummeting among Democrats and increasing among Republicans — as you can see in the figure below. No doubt these trends reflect the outcome of the 2024 election.

Overall, trust in FDA and CDC to provide reliable information on vaccines is low, with Democrats still expressing more trust than Republicans, despite recent trends.

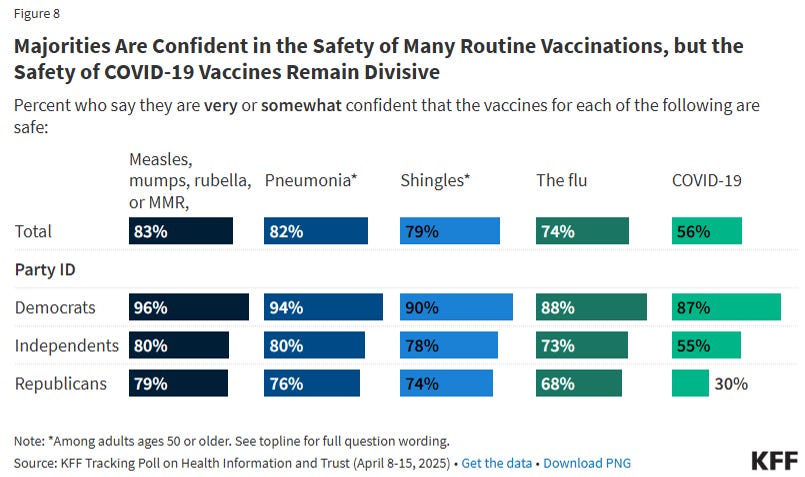

Looking a little deeper, large majorities of both Republicans and Democrats are confident in the safety of specific vaccines, with the notable exception of COVID-19, as you can see below.

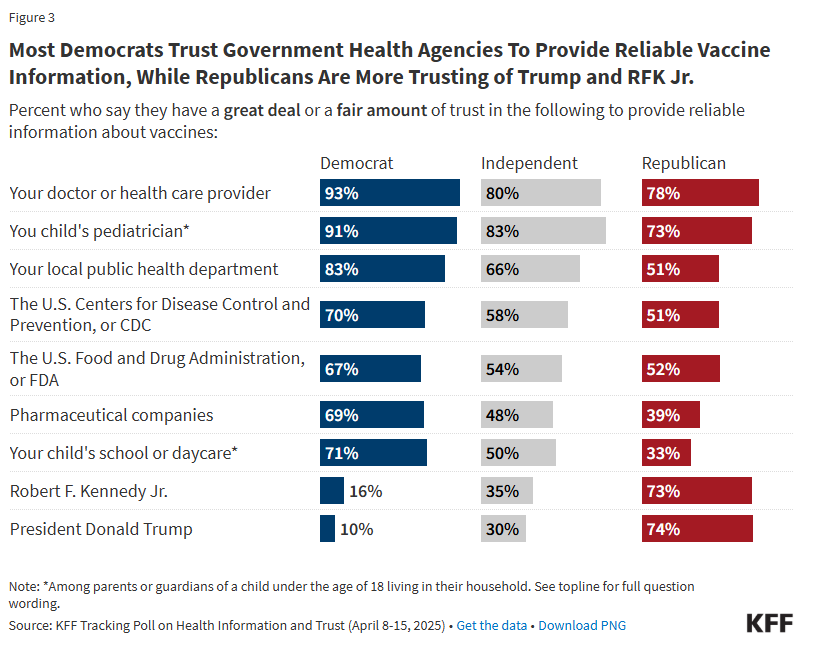

When asked who they trust to provide reliable information on vaccines, there is again a sharp partisan split, with Democrats showing more trust in government agencies than Republicans, and vice versa — extremely so — when it comes to trust in RFK Jr. and President Donald Trump.

Low and, for some, declining public trust in CDC and FDA is indeed problematic, but evidence suggests a nuanced picture, with trust significantly related to political affiliation. Any remedy to the crisis in public trust should seek to (a) close the partisan gap, and (b) increase trust across the board.

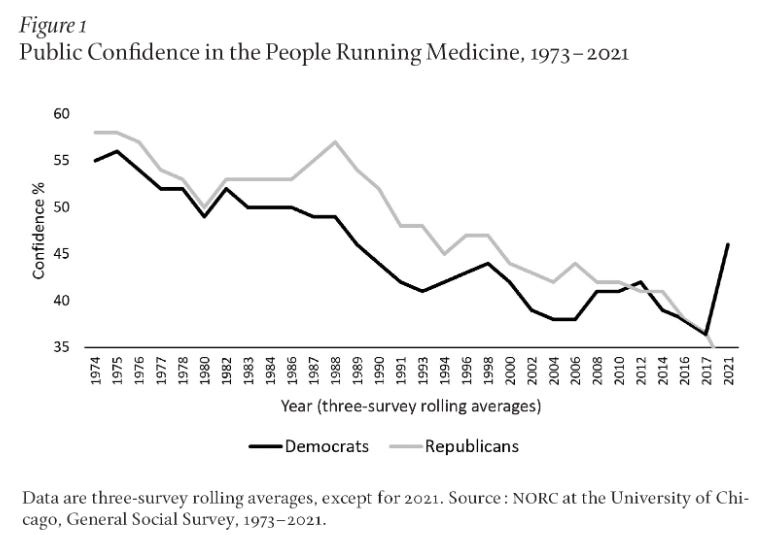

The figure below shows that over the last 50 years Republicans generally had more trust in institutions of public health than Democrats, and the trend in declining trust has been underway for decades. The figure also shows that prior to COVID-19, Republicans and Democrats exhibited similar (low) levels of trust. COVID-19 changed everything.

Given these data on the nature of the problem of public trust in institutions of public health, does RFK Jr.’s sacking of the entire ACIP committee make sense?

No, it does not.

Those who voted for Donald Trump and are still raging about the Biden Administration are those who will most likely be supportive of populating the ACIP with Trump administration appointees.2 Perhaps this group will indeed see an increase in trust.

However, for everyone else (that is, Democrats and Independents) it is just as likely that trust will be compromised. It is very difficult to envision that yesterday’s announcement will help to close the partisan gap or to increase overall trust in public health institutions.

ACIP members are limited to one four-year term, and historically, the committtee has been comprised of members appointed by HHS and CDC under administrations of different parties. The congressional act which created the ACIP (and other public health advisory committees) expressly says that committee empanelment “shall be made without regard to political affiliation.”

The Trump administration has now made ACIP committee empanelment explicitly partisan, explaining:

“The Biden administration appointed all of the 17 sitting ACIP members. Thirteen of them were appointed in 2024. These appointments would have prevented the current administration from choosing a majority of the committee until 2028.”

It is certainly problematic that the Biden administration appointed all former members of the ACIP. At the same time, it is also problematic that the Trump administration believes that they should expect to appoint a majority of the committee.

To the extent that partisan considerations play a central role in ACIP empanelment, we defeat the entire purpose of soliciting expert advice. Cherry picking experts is just as bad as cherry picking scientific studies. It allows the creation of a politically expedient portrayal of reality, but there is no guarantee that reality is real.

There are a better ways forward here, and once again, Congressional leadership is needed.

One step is a simple procedural change — Congress could amend the Public Health Service Act to lengthen the term of service of each member of ACIP to 6 years, and then stagger appointments by two years, with six members replaced every two years.3

With 18 members on the committee, that would mean that across one presidential term, each administration would be able to appoint six advisors in year one of the presidency and six more in year three. If the president is re-elected they would get to appoint six more to the panel, meaning that the entire panel would then be comprised by that administration’s appointees.

Having a fixed schedule of appointments has more potential to restore public trust in expert advice than turning expert advisors into political appointees.

More generally, there are other approaches that could be used to demonstrate to the public the importance of competency rather than allegiance, such as creating an empanelment committee at arms length from political appointees.4

There is no way to eliminate politics from formal processes of expert advice, but there are better and worse ways to manage the influence of politics on the guidance that public health experts provide to decision makers. That means choosing not to politicize institutions of expertise. Such a choice requires leadership that respects that decision making ought to be informed by the best possible expertise.

I have long argued that experts need to make peace with democracy. Just as important, policy makers need to make peace with expertise.

This article was originally published on The Honest Broker. If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing here.

1 The ACIP operates under the provisions of the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA), which “governs the establishment, operation, and termination of advisory committees within the executive branch of the Federal Government. FACA defines what constitutes a Federal advisory committee and provides general procedures for the executive branch to follow for the operation of these committees. The Act helps to ensure that Congress and the public are kept informed regarding the number, purpose, membership, activities, and cost of advisory committees.”

2 In the comments, I’d welcome hearing from Trump voters who oppose RFK Jr.’s sackings, and conversely, Biden voters who support the sackings and now have more trust in CDC. I am not interested in hearing from Trump voters who approve the sackings or Biden voters who oppose them — That is the problem! Science advice is not to be confused with cheerleading.

3 There is nothing magic about 6 years — it could be 7 or 8. The important thing here is that terms are fixed and staggered, such that at any given time there is high likelihood of members appointed under different administrations under a fixed schedule.

4 Empanelment processes for expert advisory bodies are not discussed enough. Too often they are decisions made in the proverbial smoke-filled back room. Competency is non-negotiable, but depending on the purpose of the committee, other considerations will be important as well. For instance, on highly politicized issues, securing a partisan balance may be important. Similarly, if one role of the advisory body is to secure public trust, then demographic considerations should be considered.