The optimal amount of practical wind power in the global energy mix is greater than zero. It is also much less than 100%. Today I argue why the proportion of wind power in the global electricity generation mix is always going to be closer to zero than to 100%. That doesn’t mean that wind power is not of value or useful, but it does mean that wind power is not going to drive a global energy transformation, or even be a big part of any such transformation. The sooner we realize that, the better for energy and climate policies.

This post gives explains three reasons why wind will always be niche — low density, low capacity, the age effect — and why costs are not among those reasons.

Wind Power is Low Density

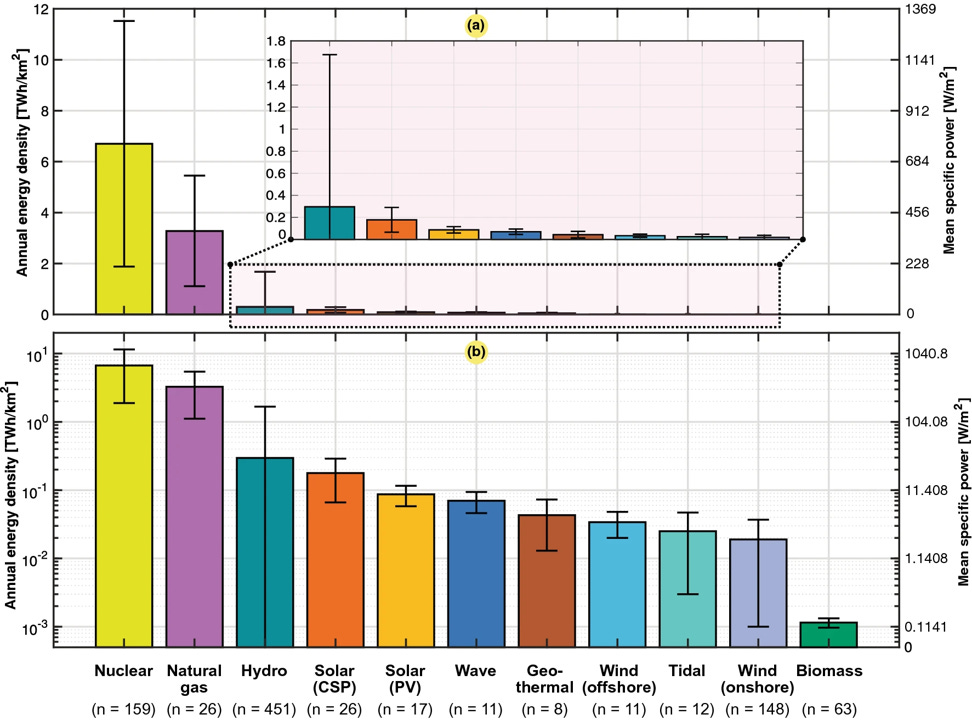

The figure above comes from a recent study by a research group in Norway of annual energy density (measured as terawatt-hours per square kilometer) for 11 different technologies of electricity production.

A first thing to notice is that the top panel — with a linear scale — shows that wind power, either onshore or offshore, does not even appear on the graph when scaled against nuclear and natural gas.

Onshore wind requires about ~370x the land area for the production of the equivalent amount of energy as nuclear (offshore requires ~200x the area of nuclear). According to this study, to meet today’s total global electricity demands using wind would require land area equal to about Brazil — or about 3% of all global land area (and this included places like Antarctica, the Sahara, and the Amazon).

The point here is not that the world would ever try to meet all of its need with wind — of course not. But the implied land (or sea) requirements alone necessary to meet any significant portion of global energy demand imply that wind can only be a niche technology. Wind power makes sense where there is ample space for deployment, ready connections to where power is needed, and integrates well with other technologies, especially necessary back-up generation.

Wind Capacity Factors are Limited

The wind does not always blow and when it does blow, turbines are not always in operation. The proportion of energy generated by a wind turbine, as compared to its nameplate capacity is called its “capacity factor.” Over time, with the extensive deployment of wind technologies around the world, capacity factors have not increased much at all, even as wind technologies have improved.

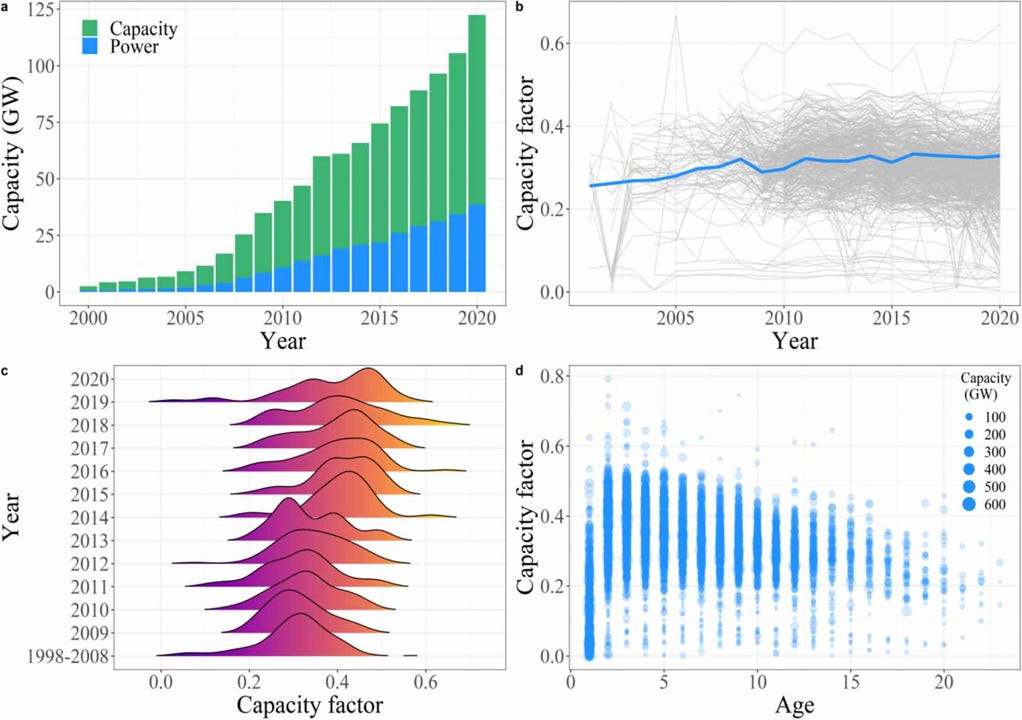

The four-paneled figure below shows different ways to look at wind energy capacity and capacity factors from 2000 to 2020.

The data show that the even as U.S. wind capacity expanded dramatically over 2000 to 2020, overall capacity factors remained fairly constant. More recent data shows that in 2023 wind capacity factors declined to an 8-year low, and early data from EIA for 2024 shows further year-on-year declines.

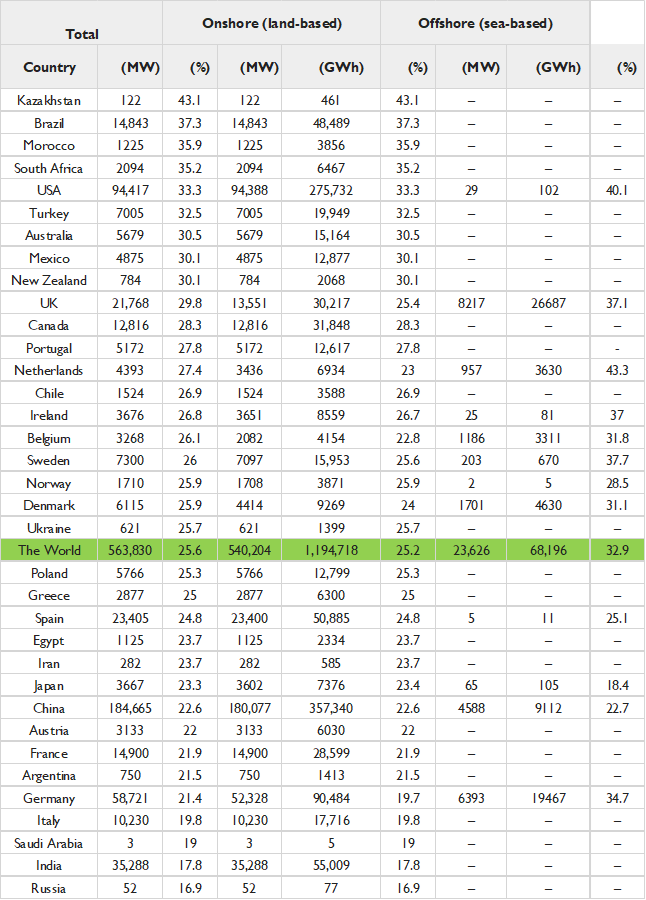

The United States is also not representative of wind power deployments around the world. The table below — sorted by onshore capacity factors, high to low — from Xu et al. 2023, shows that the United States is among the world’s best performers for wind capacity, both onshore and offshore.

The low capacity factors of wind necessarily mean that wind power needs back up. That back up might include:

- Higher capacity energy technologies, like nuclear or natural gas;

- Energy storage, such as in batteries or pumped hydro;

- Overbuilding of wind technology and easy transport of electricity from place to place.

These back-up options all raise issues — With nuclear, wind is not needed, with gas, considerable carbon dioxide emissions may still result even if wind displaces some of them, energy storage at the massive scale needed are not presently possible, and overbuilding wind and the grid seems fanciful, given the massive deployment challenges.

Once again, these numbers suggest that while wind has a future role in the global energy mix, that future will remain niche.

Wind Power Technologies Age Quickly

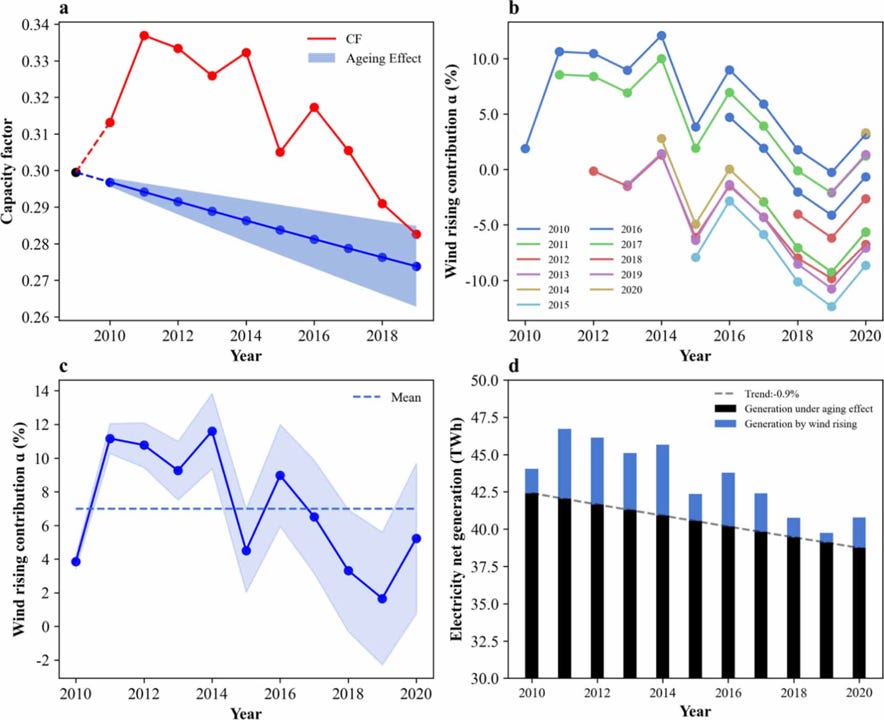

The figure below, also from Xu et al. 2023, shows that deployed wind turbines age quickly in terms of capacity factors that start decreasing at most over a few years after initial deployment.

Nuclear and natural gas power plants of course also have aging and maintenance issues, but have demonstrated nothing like the longer-term declines in capacity shown by wind turbines. The aging effect means that wind turbines may need greater back-up (than the prodigious amount already needed), need to be replaced frequently, and require extensive upkeep and maintenance.

Show me an entire U.S. state or a medium-sized country powered by wind without the issues raised above about necessary back-up, and I’ll be happy reconsider these concerns.

Notice I Haven’t Even Raised Costs

That is right. In my view, costs are not the limiting factor for the expansion of wind beyond its niche. Wind power could be completely free and it would still be low density, low capacity, and experience age effects.

Think of this analogy — walking from place to place is pretty much free. But is is also low density (i.e., it takes a long time compared to alternatives) and it is low capacity (e.g., it is difficult to ship goods by walking). Speaking for myself, there is also an age effect.

Does walking have a role to play in global movement? Sure it does? Is it capable of assuming a major role in the global energy mix? Unlikely.

Energy realism means prioritizing math, physics, politics (yes), and the societal demand for reliable and accessible electricity (and also of course, economics!). With the world committing to accelerating decarbonization — which I support — real progress can only be made by looking to energy sources that are reliable and accessible, which means more dense, higher capacity, and here for the long term.

That is not wind energy.